Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

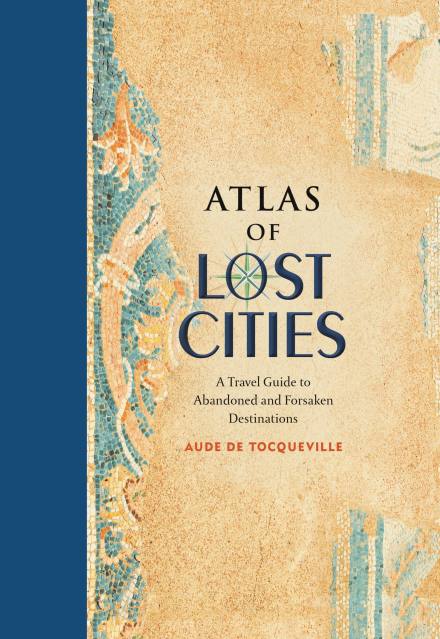

Atlas of Lost Cities

A Travel Guide to Abandoned and Forsaken Destinations

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $24.99 $32.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 5, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Cities are mortal, but the traces they leave behind tell a fascinating story. In Atlas of Lost Cities, an accomplished travel writer reveals the rise and fall of notable places, each pithy portrait illuminated by a vintage map that puts armchair explorers right in the scene. Wander with care through:

- Ancient and legendary places like Pompeii, Teotihuacá and Angkor

- Contemporary wonders like Centralia, a nearly abandoned Pennsylvania town consumed by unquenchable underground fire

- Eerie planned communities like Nova Citas de Kilamba in Angola, where housing, schools, and stores were built for 500,000 people who never came

- Epecuen, a tourist town in Argentina that was swallowed by water

With each map are fantastical illustrations that help the reader envision these hubs as they were in their prime. A perfect gift for the traveler who believes he or she has seen it all.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 5, 2016

- Page Count

- 144 pages

- Publisher

- Black Dog & Leventhal

- ISBN-13

- 9780316355827

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use