By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

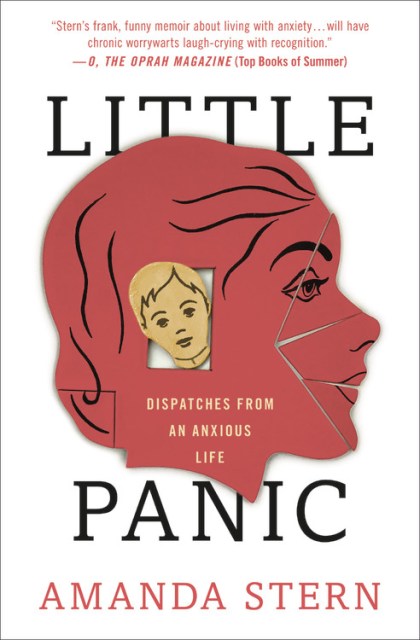

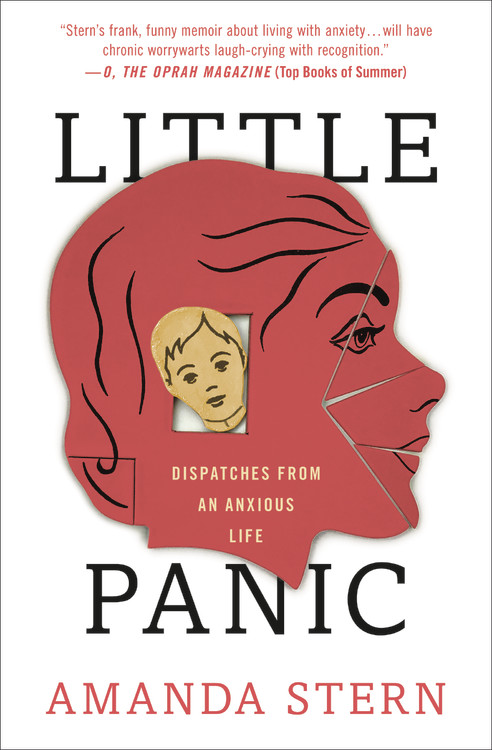

Little Panic

Dispatches from an Anxious Life

Contributors

By Amanda Stern

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 14, 2019

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538711941

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 14, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In the vein of bestselling memoirs about mental illness like Andrew Solomon’s Noonday Demon, Sarah Hepola’s Blackout, and Daniel Smith’s Monkey Mind comes a gorgeously immersive, immediately relatable, and brilliantly funny memoir about living life on the razor’s edge of panic.

The world never made any sense to Amanda Stern–how could she trust time to keep flowing, the sun to rise, gravity to hold her feet to the ground, or even her own body to work the way it was supposed to? Deep down, she knows that there’s something horribly wrong with her, some defect that her siblings and friends don’t have to cope with.

Growing up in the 1970s and 80s in New York, Amanda experiences the magic and madness of life through the filter of unrelenting panic. Plagued with fear that her friends and family will be taken from her if she’s not watching-that her mother will die, or forget she has children and just move away-Amanda treats every parting as her last. Shuttled between a barefoot bohemian life with her mother in Greenwich Village, and a sanitized, stricter world of affluence uptown with her father, Amanda has little she can depend on. And when Etan Patz disappears down the block from their MacDougal Street home, she can’t help but believe that all her worst fears are about to come true.

Tenderly delivered and expertly structured, Amanda Stern’s memoir is a document of the transformation of New York City and a deep, personal, and comedic account of the trials and errors of seeing life through a very unusual lens.

The world never made any sense to Amanda Stern–how could she trust time to keep flowing, the sun to rise, gravity to hold her feet to the ground, or even her own body to work the way it was supposed to? Deep down, she knows that there’s something horribly wrong with her, some defect that her siblings and friends don’t have to cope with.

Growing up in the 1970s and 80s in New York, Amanda experiences the magic and madness of life through the filter of unrelenting panic. Plagued with fear that her friends and family will be taken from her if she’s not watching-that her mother will die, or forget she has children and just move away-Amanda treats every parting as her last. Shuttled between a barefoot bohemian life with her mother in Greenwich Village, and a sanitized, stricter world of affluence uptown with her father, Amanda has little she can depend on. And when Etan Patz disappears down the block from their MacDougal Street home, she can’t help but believe that all her worst fears are about to come true.

Tenderly delivered and expertly structured, Amanda Stern’s memoir is a document of the transformation of New York City and a deep, personal, and comedic account of the trials and errors of seeing life through a very unusual lens.

-

"...Stern's bold work is told with insight and humor..."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px Helvetica}Real Simple, Great Books to Help You Relax and De-Stress

-

There's something magnetic about Little Panic.Goop

-

"In this canny, insightful, novelistic memoir, Amanda Stern traces the indelible path her underlying anxiety has traced in a rich but often frustrated life. It's a book about her emergence into and acceptance of mature identity, but it is also about the danger of love, the maze of social pressure, and the tension between childhood expectations and adult realities. Narrating with real poignance how every experience she's had has been filtered through her psychic vulnerability, she achieves a symphony of complex fragilities and redeeming strengths."Andrew Solomon, National Book Award-winning author of Far From the Tree

-

"Amanda Stern has written an affecting, emotionally vivid memoir that really succeeds in giving the reader the sense of what it might be like to be another person, with all the experiences and sensations-including the most difficult ones-that that entails. Her book is reflective, authentic, alive."Meg Wolitzer, New York Times bestselling author of The Female Persuasion

-

"Little Panic is an intimate and sweeping story of hyper-vigilance. Cheeky and vivid and transporting, it's also extremely funny. Stern's book conveys just how isolating mental illness really is, how it creates almost a second existence for those who suffer it. As I read it I had the sense of someone living underwater, watching the world going on effortlessly above. I was swept up. I spend my life hoping to find books like this."Sarah Manguso, author of 300 Arguments: Essays

-

"With courage and a keen sense of humor, Little Panic delves beneath the surface of the terms, tests, and judgements we apply to our mental existence in order to recover the experiential richness buried beneath. Readers will recognize themselves in Stern's psychological coming-of-age, keenly empathetic and vibrantly felt."Alexandra Kleeman, author of You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine

-

"Brave, in the truest sense of the word, Amanda Stern's Little Panic is a document of survival of the fittest. This is the book for anyone-who has dropped a beat, a week or a year, feeling afraid not just of the dark, but of life, of being left alone in this world. A haunting story of the impact of time and place-the backdrop of Etan Patz's vanishing, New York in the 1970s-split between parents and worlds, struggling to find a place of her own. Little Panic is a stunning reminder of what it is to be human."A. M. Homes, bestselling author of The Mistress's Daughter and Days of Awe

-

"Amanda Stern sees childhood with perfect clarity, and she sees how we, as adults, are still living in childhood. Little Panic will make you feel alot. Without a doubt, it is a masterpiece."Darin Strauss, author of Half a Life

-

"Stern has succeeded in writing an often-funny tale about mental illness....A good reminder that all people, including those who "learn differently," need empathy and human connection."Booklist

-

"Moving...vivid and illuminating."BBC, "Ten Books to Read in June"

-

"Stern's frank, funny memoir about living with anxiety...will have chronic worrywarts laugh-crying with recognition."O, The Oprah Magazine

-

"Brave, fiercely funny...a brilliant read that offers hope for anyone burdened by anxiety. "People Magazine

-

"Visceral, pulsating realness. Alternating between past and present, Amanda details the growing anxiety of America through her own experience while weaving in a richly portrayed, fascinating portrait of New York's bohemian Greenwich Village scene of the 1970s and '80s. If you suffer from anxiety or are simply curious about the experience, it's a must-read."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}MIND BODY GREEN, 5 BOOKS YOU WONT BE ABLE TO PUT DOWN THIS JULY

-

"Amanda Stern paints a painfully honest and heartbreaking picture of her life living with an anxiety disorder....LITTLE PANIC will make you feel less alone."Hello Giggles

-

"Resonant and often funny."New York Times Book Review

-

"Entertaining and sad and funny and relatable....LITTLE PANIC grips and discomfits in the best way."Salon

-

"We haven't heard this story before, and with about 1 in 5 children diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and about and 1 in 4 adults, this is a story that needs to be heard."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 12.0px 'Times New Roman'}Psychology Today

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use