Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

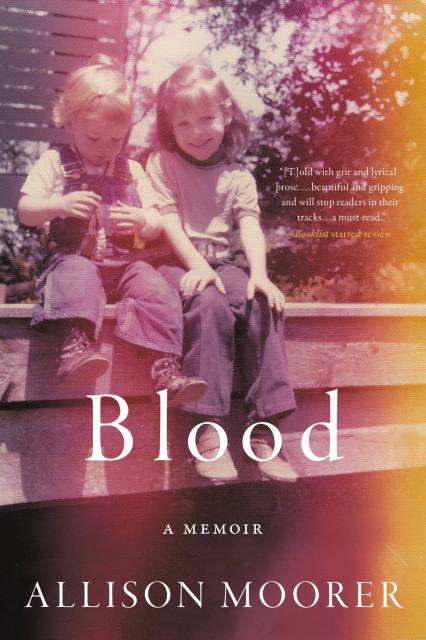

Blood

A Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 27, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306922695

Price

$15.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $21.99 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 27, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Grammy- and Academy Award- nominated singer-songwriter’s haunting, lyrical memoir, sharing the story of an unthinkable act of violence and ultimate healing through art

Mobile, Alabama, 1986. A fourteen-year-old girl is awakened by the unmistakable sound of gunfire. On the front lawn, her father has shot and killed her mother before turning the gun on himself. Allison Moorer would grow up to be an award-winning musician, with her songs likened to “a Southern accent: eight miles an hour, deliberate, and very dangerous to underestimate” (Rolling Stone). But that moment, which forever altered her own life and that of her older sister, Shelby, has never been far from her thoughts. Now, in her journey to understand the unthinkable, to parse the unknowable, Allison uses her lyrical storytelling powers to lay bare the memories and impressions that make a family, and that tear a family apart.

Blood delves into the meaning of inheritance and destiny, shame and trauma — and how it is possible to carve out a safe place in the world despite it all. With a foreword by Allison’s sister, Grammy winner Shelby Lynne, Blood reads like an intimate journal: vivid, haunting, and ultimately life-affirming.

-

"Beautiful, heart-wrenching . . . Moorer's masterful, comforting storytelling may serve as solace for those who've faced abuse, a signal for those in it to get out, and an eye-opener for others."Publishers Weekly starred review

-

"Moorer's memoir is full of backstory-memories, current notes and thoughts, and well-described metaphors that come together fluidly, all told with grit and lyrical prose. ...Her writing is beautiful and gripping and will stop readers in their tracks...a must-read."Booklist starred review

-

"There is much wisdom in her experience as well as in her reflections on what she has read and heard....Much different from most musicians' memoirs and of much interest to all who wrestle to understand tragedies of their own."Kirkus Reviews, starred review

-

"Allison Moorer is known for songs of ragged, poetic honesty -- and for the emotional clarity of her country western ballads. Her debut memoir exhibits these qualities and more."LitHub, one of the most anticipated books of 2019

-

"There are few writers -- few people, in fact -- who could examine with such profound bravery the immense suffering and trauma in her story, infuse it with a lyrical sense of timelessness, and make us feel grateful for the telling. Blood is both unflinching and redemptive: a song of loss and courage."Rosanne Cash

-

"Like her songwriting, Moorer's prose is steeped in a rich sense of place, vivid characterization, and a story you will never forget. Not since Joan Didion's Blue Nights has grief been explored with so much beauty and complexity."Silas House, author of Southernmost

-

"Grit and grace, beauty and pain, on every wise page. Allison Moorer has given us a memoir as bloody, rich, and complex as red Alabama clay."Alice Randall, author of The Wind Done Gone

-

"Blood reveals the complicated mess of love and hurt that all too many readers will recognize. Moorer herself survived the unimaginable, and her poetic testimony should summon vigorous new attention to the public-health crisis that is male anger."Sarah Smarsh, author of Heartland

-

"Blood is the most vulnerable work you're likely to read for quite some time."Rick Bass, author of For a Little While

-

"[A] harrowing debut."Elle

-

"Her voice rings with equal parts defiance and vulnerability."Blender

-

"[Moorer's] written this book like a symphony. It is expansive, and its three parts feel like movements. Moorer fills them with prose that has the sharp honesty of the greatest songwriters."The Bitter Southerner

-

"Written with brave, clear-eyed compassion for all involved, Blood is an astonishing and moving meditation on family inheritance and acceptance. Despite her family's singularly tragic circumstances, Blood tells a universal story about the things our parents pass down to us -- what we learn to be grateful for, what we release ourselves from, and what we simply leave alone."Jennifer Palmieri, author of Dear Madame President