Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

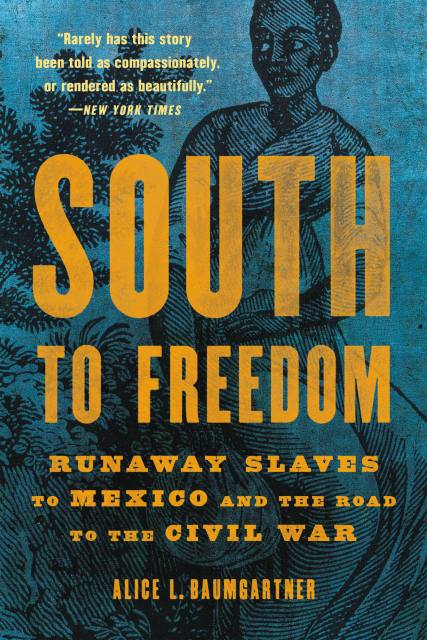

South to Freedom

Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 10, 2020

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541617773

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 10, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Underground Railroad to the North promised salvation to many American slaves before the Civil War. But thousands of people in the south-central United States escaped slavery not by heading north but by crossing the southern border into Mexico, where slavery was abolished in 1837.

In South to Freedom, historianAlice L. Baumgartner tells the story of why Mexico abolished slavery and how its increasingly radical antislavery policies fueled the sectional crisis in the United States. Southerners hoped that annexing Texas and invading Mexico in the 1840s would stop runaways and secure slavery’s future. Instead, the seizure of Alta California and Nuevo México upset the delicate political balance between free and slave states. This is a revelatory and essential new perspective on antebellum America and the causes of the Civil War.

-

“The story of how Black people in a slaveholding society affected federal policy by their movements, by their defiance and by their very existence has been told before. But rarely has this story been told as compassionately, or rendered as beautifully….Masterfully researched….Baumgartner’s important conclusion is that we must reconceive the impact of the supposedly powerless on the economically and politically powerful.”The New York Times Book Review

-

“Scholars of the Underground Railroad have long known that a small stream of runaways escaped to Mexico, but Alice Baumgartner’s South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War offers its first full accounting….It is primarily concerned with understanding why the U.S. failed to stop slavery’s expansion, why Mexico did, and using that knowledge to cast the coming of the Civil War in a new light….Baumgartner has achieved a rare thing: She has made an important academic contribution, while also writing in beautiful, accessible prose.”The New Republic

-

“A meticulously researched monograph that examines the political and diplomatic relations between Mexico and the United States to explain how Black movement south paved the road to conflicts such as the Texas Revolution, the Mexican-American War, and ultimately the Civil War....South to Freedom makes a significant contribution to borderlands history.”Los Angeles Review of Books

-

“Baumgartner brilliantly enhances our understanding of the antebellum period and the Civil War by turning toward ‘slavery’s other border.’”National Book Review

-

“Gripping and poignant….Unlike many experts who study the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, [Ms. Baumgartner] has crafted her book from Mexican as well as American archival collections, and she is deeply versed in the secondary historical literature of both countries….Ms. Baumgartner describes, with skill and great sensitivity, the experiences of those enslaved men and women who, in resisting their oppression, bravely quit the United States altogether. Their stories challenge the glib assumption held by many Americans—those of the 19th century as well as the 21st—who have long taken for granted the idea of Mexican national inferiority. Most of all, their accounts serve as a stark reminder of the severely circumscribed nature of liberty in the antebellum United States and its tragic costs not only for the enslaved but also the republic itself.”The Wall Street Journal

-

“Baumgartner’s book explores an underrecognized period when the US couldn’t so easily claim a position of moral leadership.”Literary Hub

-

“Baumgartner’s debut book deftly traces parallels between Mexico and the U.S., examining why both permitted and later abolished slavery while offering insights on how the past continues to shape the two countries’ relationship.”Smithsonian

-

“Baumgartner is a rising star in an emerging generation of historians who focus on the social forces underlying political conflict….She reverses the contemporary narrative that assumes U.S. norms and institutions are superior: in the mid-nineteenth century, Mexico was a safe haven for fugitives fleeing oppression, and the Mexican constitution was more consistent in defending universal rights than were U.S. laws.”Foreign Affairs

-

“This revelatory look at the enslaved people who did not follow the north star sheds new light on Mexican influence on U.S. history.”Shelf Awareness

-

“Deeply researched and eloquently argued....Baumgartner's fast-paced yet detailed exploration is consistently illuminating and offers a new way to understand the past....A must read.”BookPage

-

“Baumgartner brings to life the stories of slaves who escaped to Mexico and how they made it to freedom….Well-written and well-researched.”Library Journal

-

“Baumgartner debuts with an eye-opening and immersive account of how Mexico’s antislavery laws helped push America to civil war....This vivid history of 'slavery’s other border' delivers a valuable new perspective on the Civil War.”Publishers Weekly

-

"A lucid exploration of a little-known aspect of the history of slavery in the US."Kirkus

-

"South to Freedom reorders the way we should think and teach about the slavery expansion crisis in the middle of the nineteenth century. Indeed, it reorders how to think about the huge question of the coming of the American Civil War. Not many books these days can make that claim. With astonishing research and graceful writing, this one can."David W. Blight, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom

-

"Enslaved freedom-seekers in the antebellum United States looked not only to the North Star, but also to the southern border with Mexico. In a fast-paced narrative that moves deftly between the histories of both countries, Alice Baumgartner demonstrates the far-reaching impact of Mexico's free-soil policies. She shows, with eloquence and insight, how enslaved people themselves ignited the fuse that led to a civil war -- and the final abolition of slavery on the North American continent."W. Caleb McDaniel, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America

-

"In this deeply researched and pathbreaking study of southern slaves who escaped to Mexico and carved out new lives in the decades prior to the Civil War, Alice Baumgartner has succeeded in explaining a mystery that historians had been unable to unravel. How many slaves ran South to freedom, rather than North, and how did their assertiveness influence the coming of the Civil War? Baumgartner explores not only the familiar sectional controversy that led the southern states to secede from the union, but more importantly, South to Freedom examines the rich and complicated lives and the multifaceted roles that enslaved people played in Mexico. This book will contribute immensely to our understanding of sectional politics, as well as the manner in which Mexico asserted its 'moral power' to reject an inhumane institution and to assist fugitive slaves in recreating their lives as free men and women."Albert S. Broussard, author of Black San Francisco: The Struggle for Racial Equality in the West, 1900-54

-

"Taken for granted, borders between two nations have the power to constrain curiosity and limit the self-understanding of both nations. But when the research of a gifted historian defies a border, as Alice L. Baumgartner's South to Freedom demonstrates, the result is the revelation of a story of great consequence. When Texas slaves seized the opportunities presented by Mexico's precedent-setting initiatives in emancipation, the actions of a comparatively small group of people shaped a historical event of enormous scale: the American Civil War."Patricia Nelson Limerick, author of The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West