By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

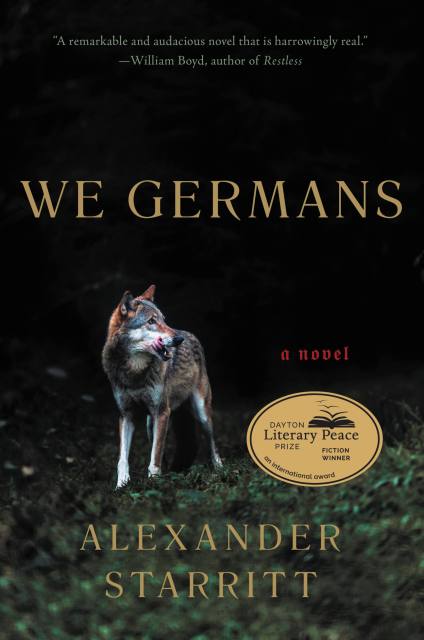

We Germans

A Novel

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 1, 2020

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316429801

Price

$34.00Price

$44.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $34.00 $44.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $33.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 1, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

WINNER OF THE DAYTON LITERARY PEACE PRIZE

A letter from a German soldier to his grandson recounts the terrors of war on the Eastern Front, and a postwar ordinary life in search of atonement, in this “raw, visceral, and propulsive” novel (New York Times Book Review).

A letter from a German soldier to his grandson recounts the terrors of war on the Eastern Front, and a postwar ordinary life in search of atonement, in this “raw, visceral, and propulsive” novel (New York Times Book Review).

A New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice

In the throes of the Second World War, young Meissner, a college student with dreams of becoming a scientist, is drafted into the German army and sent to the Eastern Front. But soon his regiment collapses in the face of the onslaught of the Red Army, hell-bent on revenge in its race to Berlin. Many decades later, now an old man reckoning with his past, Meissner pens a letter to his grandson explaining his actions, his guilt as a Nazi participator, and the difficulty of life after war.

Found among his effects after his death, the letter is at once a thrilling story of adventure and a questing rumination on the moral ambiguity of war. In his years spent fighting the Russians and attempting afterward to survive the Gulag, Meissner recounts a life lived in perseverance and atonement. Wracked with shame—both for himself and for Germany—the grandfather explains his dark rationale, exults in the courage of others, and blurs the boundaries of right and wrong.

We Germans complicates our most steadfast beliefs and seeks to account for the complicity of an entire country in the perpetration of heinous acts. In this breathless and page-turning story, Alexander Starritt also presents us with a deft exploration of the moral contradictions inherent in saving one’s own life at the cost of the lives of others and asks whether we can ever truly atone.

-

“Starritt’s prose is riveting. It unspools like a roll of film—raw, visceral, and propulsive, rich with sensory detail and unsparing in its depictions of cruelty . . . As I struggle to make sense of the polarized world we live in today, We Germans feels eerily timely. Meissner’s and Callum’s puzzlements are ours: How do we hold ourselves—and our ancestors—accountable for past wrongs? How do we acknowledge and atone for a nation’s violations? Starritt’s daring work challenges us to lay bare our histories, to seek answers from the past, and to be open to perspectives starkly different from our own.”Georgia Hunter, New York Times Book Review

-

"Striking... Vividly done... The book has a gritty realism... We Germans is a visceral examination of guilt, collective and individual."Andrew Holgate, Sunday Times

-

"Haunting... Daringly, in this slim, taut novel, Alexander Starritt climbs into the skin of one of the most appalling archetypes of the 20th century: a Nazi soldier... Starritt's descriptions of conflict are shocking... We Germans captures the terrible moment of realization when it dawns on the once-swaggering, all-conquering Nazis that they are going to be crushed... Although no readers are likely to admire the soldier's wartime actions, they will at least be confronted by his experiences as both killer and victim."John Thornhill, Financial Times

-

"An impressively realistic novel of German soldiers on the eastern front, raising the fundamental questions of individual and collective guilt."Antony Beevor, Pritzker Award-winning author of Stalingrad and the #1 International Bestseller The Second World War

-

“We Germans stands out among WWII novels…a quick and compelling read.”Lorelei Brush, Historical Novel Society

-

"We Germans is a remarkable and audacious novel that is harrowingly real and, at the same time, asks the most searching questions about men at war."William Boyd, Booker Prize finalist and author of Any Human Heart and Restless

-

“A thoughtful, unsettling chronicle… Starritt’s gritty depictions of the horrors of war and the moral choices faced by soldiers add intensity to the ruminations on courage. This is a fascinatingly enigmatic addition to the literature of Germany’s coming to terms with the past.”Publishers Weekly

-

“A small masterpiece... Starritt shows courage in his approach... A risky, provocative novel with exceptional writing.”Kirkus Reviews

-

“We Germans will intrigue fans of introspective, morally complex war fiction narrated from the perspective of those who served, such as works by war veterans Tim O'Brien and Phil Klay.”Lindsay Harmon, Booklist

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use