By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

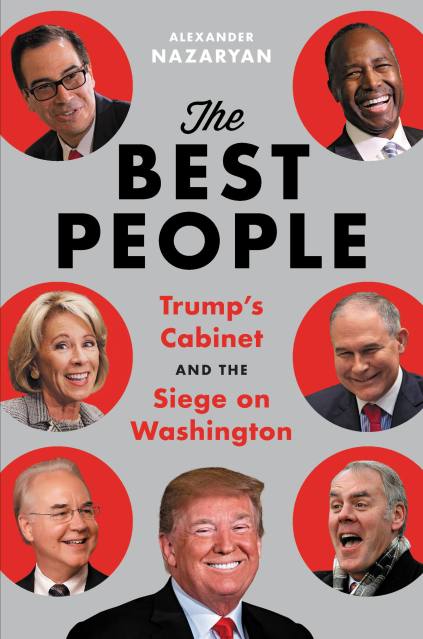

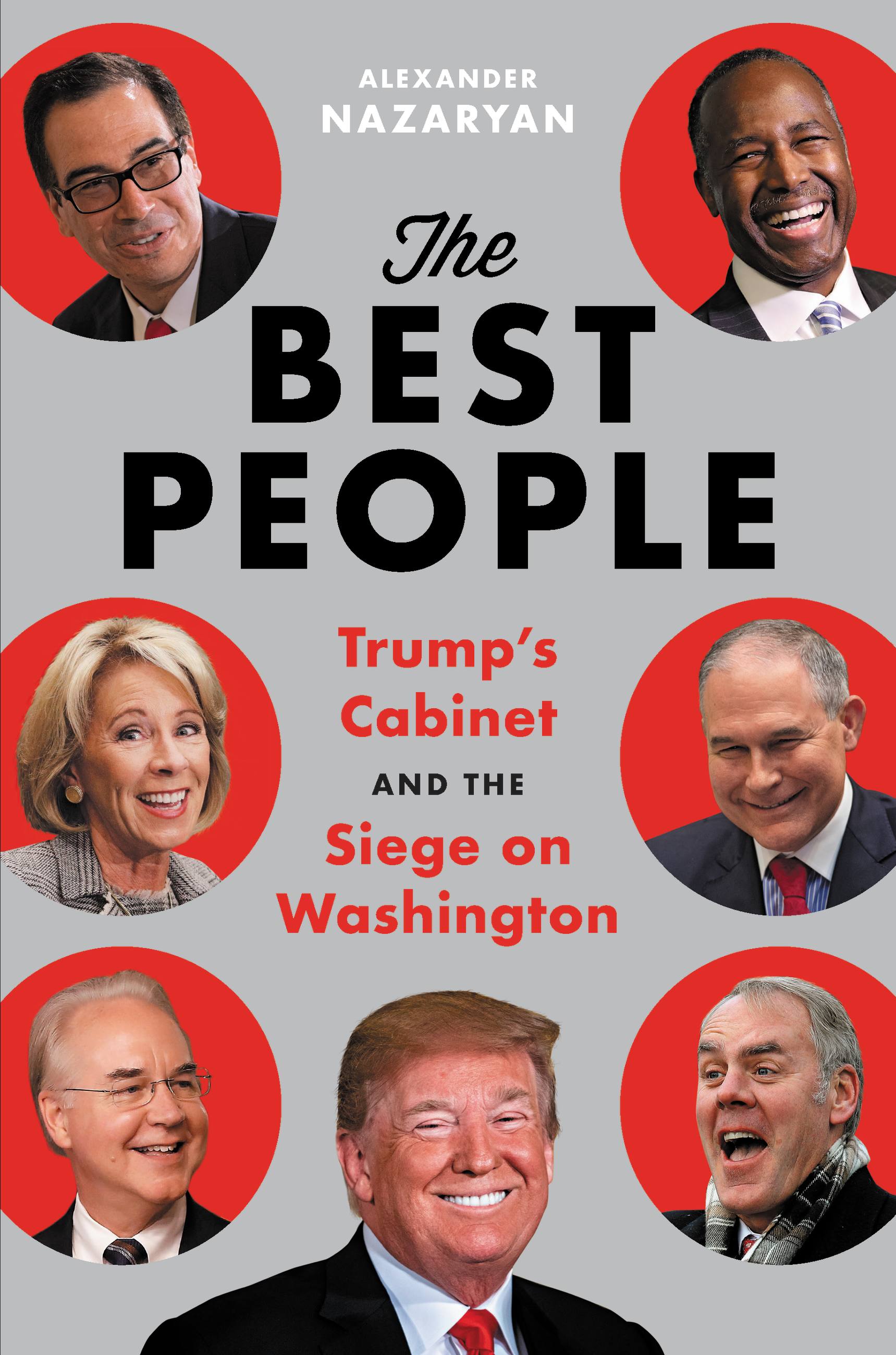

The Best People

Trump's Cabinet and the Siege on Washington

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 18, 2019

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316421423

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 18, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

An engrossing look at the Trump cabinet: the scandals, the incompetence, the assault on the federal government, the bungled attempts to impose order on an administration lost in a chaos of its own making.

Donald Trump promised a return to national greatness, but each day of his presidency seems to bring a new crisis, a deepening sense of national unease. Why, and how, has he failed his supporters? And how has he, on occasion, bested his detractors?

The Best People takes complete measure of the Trump administration, to grasp with clarity the president and his intentions, and how those intentions are being carried out-or subverted-by the people he has hired.

Alexander Nazaryan argues that the “assault on the administrative state” promised by Steve Bannon in early 2017 never came. What the American people got instead was Wilbur Ross hauling his tennis pro to confirmation hearing preparations; Scott Pruitt running away from rattlesnakes; Reince Priebus enduring insults from junior White House staffers.

And yet, bungling as Trump’s cabinet members have been, they have managed to either damage or arrest many of the gears that make government run. They have given away public lands to oil companies and allowed corporate lobbyists to make decisions about what is best for the American people, and have done it all while flying on private jets and dining at the finest restaurants, at taxpayers’ expense.

Meticulously reported and enthrallingly told, The Best People takes readers inside the federal government under Trump’s control, a government assailed by the very people charged to lead it, a government awash in confusion and corruption.

-

"An essential exposé of the first two years of the Trump administration.... the first to fully capture just how dysfunctional - and destructive - Trump's executive branch has turned out to be."The Washington Post

-

"Alexander Nazaryan offers a field guide to the black lagoon of Trumpworld."The Guardian

-

"[The] most authoritative look at the Trump cabinet, period."AOL Build

-

"A fascinating read."Charlie Sykes, "The Bulwark" podcast

-

"Nazaryan shows clearly how Donald Trump, with his 'intentionally nonlinear presidency,' established a Cabinet consisting of crucially inexperienced individuals in public service, each remarkably unqualified to assume key pivotal decision-making roles in politics ... Nazaryan provides glaring examples of the rampant conflicts of interests and ethical red flags... A fresh spin on a dire situation .... A dizzying, tragicomic crash course in contemporary political incapacities."Kirkus Reviews

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use