By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

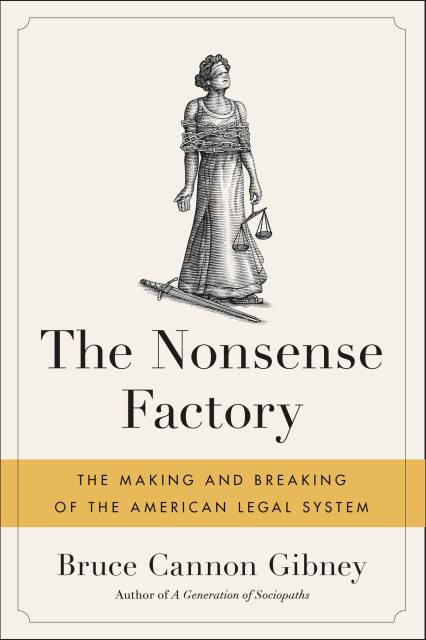

The Nonsense Factory

The Making and Breaking of the American Legal System

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 12, 2020

- Page Count

- 544 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316475280

Price

$19.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 12, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A withering and witty examination of how the American legal system, burdened by complexity and untrammeled growth, fails Americans and threatens the rule of law itself, by the acclaimed author of A Generation of Sociopaths.

Our trial courts conduct hardly any trials, our correctional systems do not correct, and the rise of mandated arbitration has ushered in a shadowy system of privatized “justice.” Meanwhile, our legislators can’t even follow their own rules for making rules, while the rule of law mutates into a perpetual state of emergency. The legal system is becoming an incomprehensible farce. How did this happen?

In The Nonsense Factory, Bruce Cannon Gibney shows that over the past seventy years, the legal system has dangerously confused quantity with quality and might with legitimacy. As the law bloats into chaos, it staggers on only by excusing itself from the very commands it insists that we obey, leaving Americans at the mercy of arbitrary power. By examining the system as a whole, Gibney shows that the tragedies often portrayed as isolated mistakes or the work of bad actors — police misconduct, prosecutorial overreach, and the outrages of imperial presidencies — are really the inevitable consequences of law’s descent into lawlessness.

The first book to deliver a lucid, comprehensive overview of the entire legal system, from the grandeur of Constitutional theory to the squalid workings of Congress, The Nonsense Factory provides a deeply researched and witty examination of America’s state of legal absurdity, concluding with sensible options for reform.

-

"Law schools seeking a good overview could save themselves the trouble and just assign entering students [The Nonsense Factory].... A plain-English "wide-angle critique" of the legal system... Ambitious.... Non-lawyers and many attorneys, too, will certainly have a better sense of what ails our justice system after reading this book."Washington Post

-

"The Nonsense Factory is a provocative polemic on the sorry state of American law. Whether you chiefly blame the Supreme Court or Congress or law professors or We The People ourselves--and whether or not you buy into every count of his indictment--Gibney's book raises serious questions about how we govern ourselves."David A. Kaplan, author of The Most Dangerous Branch: Inside the Supreme Court's Assault on the Constitution

-

"A diligent, carefully considered overview of the law and its many facets.... Gibney is an insurrectionist with a heavy mind but a light heart.... His overarching intellectual project is a deeply admirable, and indeed, a patriotic one. He's willing to take a little heat to get some new ideas out there, and he's willing to make a few enemies in the process. By applying his deeply agile mind to the seemingly intractable obstacles of our democracy, he implicitly and crucially demonstrates the belief that real solutions exist."Lawyers, Guns, and Money

-

"A keen, lively deconstruction of the American legal system's seemingly countless flaws."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Gibney is ... often funny, and his criticisms are serious, well-argued, and provocative."Publishers Weekly

-

"Gibney (A Generation of Sociopaths) boldly declares that these chaotic times have been long-developing in the legal realm.... A timely investigation of the 'Imperial Presidency' considers the history and dangers of executive power. Ultimately, Gibney calls for structural reform and corrective actions.... Civic-minded readers .... will enjoy this ambitious and wry polemic on America's legal system."Library Journal

-

"Monumental and hugely entertaining...smart, funny, incisive...."Good Law Bad Law podcast with Aaron Freiwald

-

"[A] sweeping new study of America's legal system."Jeff Jacoby, Boston Globe

-

"Really interesting book... stirring the pot."The Young Turks

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use