Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

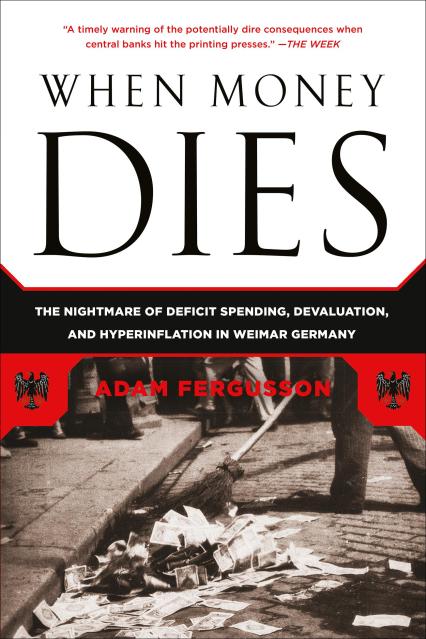

When Money Dies

The Nightmare of Deficit Spending, Devaluation, and Hyperinflation in Weimar Germany

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 12, 2010

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781586489946

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 12, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The classic history of the political and economic devastation wrought by runaway inflation in Weimar Germany—“brilliant” (Guardian)

In 1923, with its currency effectively worthless (the exchange rate in December of that year was one dollar to 4,200,000,000,000 marks), the German republic was all but reduced to a barter economy. Expensive cigars, artworks, and jewels were routinely exchanged for staples such as bread; a cinema ticket could be bought for a lump of coal; and a bottle of paraffin for a silk shirt. People watched helplessly as their life savings disappeared and their loved ones starved. Germany’s finances descended into chaos, with severe social unrest in its wake.

Money may no longer be physically printed and distributed in the voluminous quantities of 1923. However, “quantitative easing,” that modern euphemism for surreptitious deficit financing in an electronic era, can no less become an assault on monetary discipline. Whatever the reason for a country’s deficit—

necessity or profligacy, unwillingness to tax or blindness to expenditure—it is beguiling to suppose that if the day of reckoning is postponed economic recovery will come in time to prevent higher unemployment or deeper recession. What if it does not? Germany in 1923 provides a vivid, compelling, sobering moral tale.

In 1923, with its currency effectively worthless (the exchange rate in December of that year was one dollar to 4,200,000,000,000 marks), the German republic was all but reduced to a barter economy. Expensive cigars, artworks, and jewels were routinely exchanged for staples such as bread; a cinema ticket could be bought for a lump of coal; and a bottle of paraffin for a silk shirt. People watched helplessly as their life savings disappeared and their loved ones starved. Germany’s finances descended into chaos, with severe social unrest in its wake.

Money may no longer be physically printed and distributed in the voluminous quantities of 1923. However, “quantitative easing,” that modern euphemism for surreptitious deficit financing in an electronic era, can no less become an assault on monetary discipline. Whatever the reason for a country’s deficit—

necessity or profligacy, unwillingness to tax or blindness to expenditure—it is beguiling to suppose that if the day of reckoning is postponed economic recovery will come in time to prevent higher unemployment or deeper recession. What if it does not? Germany in 1923 provides a vivid, compelling, sobering moral tale.

-

“Engrossing and sobering.”Daily Express (London)

-

“One of the most blood chilling economics books I’ve ever read.”Allen Mattich, Wall Street Journal

-

“Everybody ought to read this book. But Baby Boomers must.”Wall Street Journal

-

”A brilliant account of how Germany's Weimar Republic was consumed by hyperinflation.”The Guardian

-

“A timely warning of the potentially dire consequences when central banks hit the printing presses.”The Week