Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

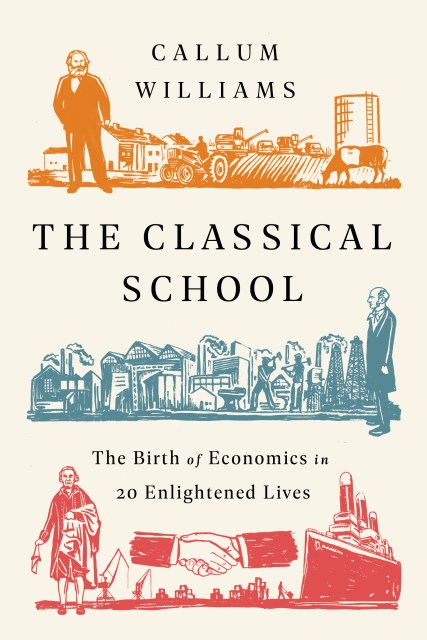

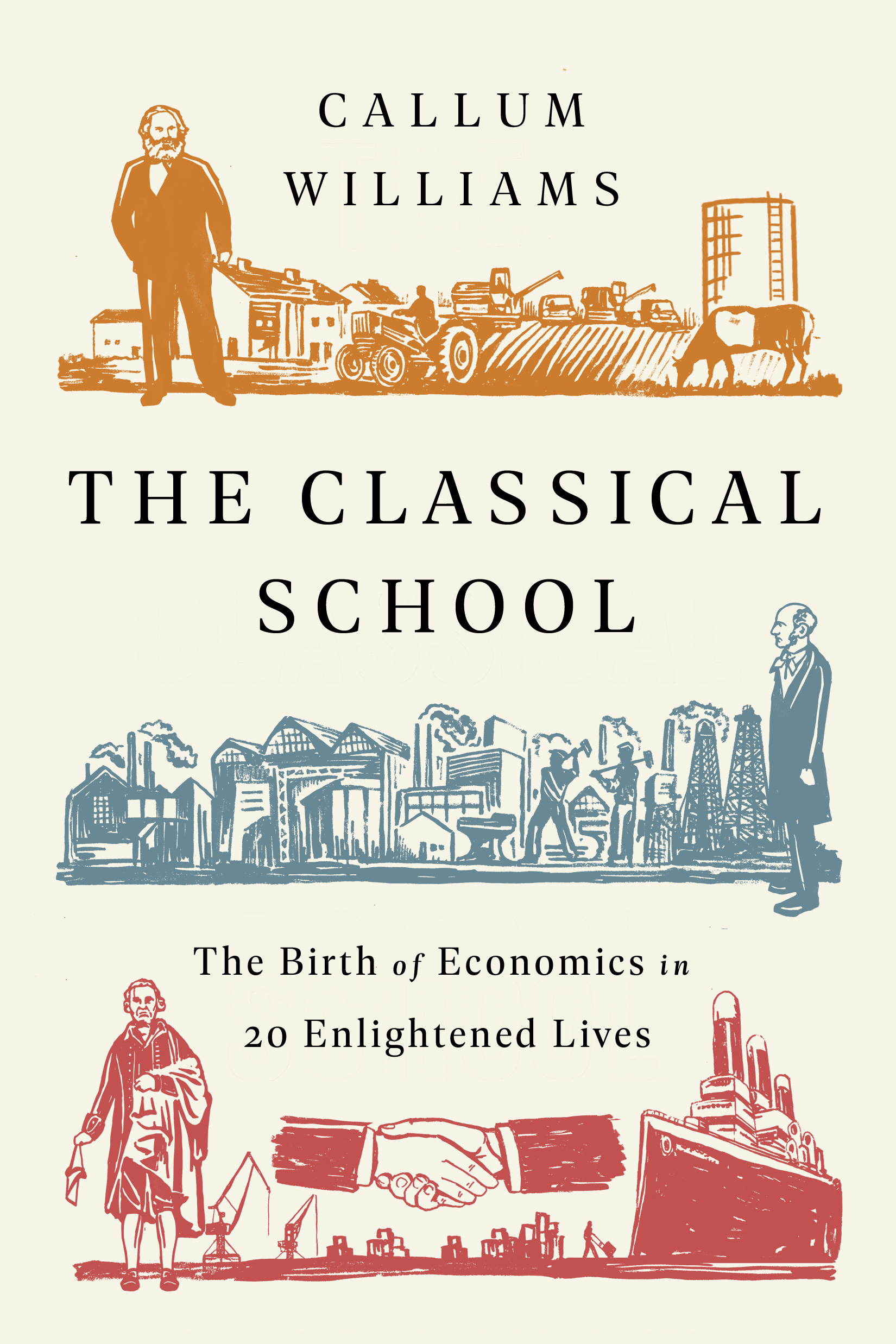

The Classical School

The Birth of Economics in 20 Enlightened Lives

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 19, 2020

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541762695

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 19, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

What was Adam Smith really talking about when he mentioned the “invisible hand”? Did Karl Marx really predict the end of capitalism? Did Thomas Malthus (from whose name the word “Malthusian” derives) really believe that famines were desirable?

In The Classical School, Callum Williams debunks popular myths about these great economists, and explains the significance of their ideas in an engaging way. After reading this book, you will know much more about the very famous (Smith, Ricardo, Mill) and the not-quite-so-famous (Bernard de Mandeville, Friedrich Engels, Jean-Baptiste Say). The book offers an assessment of what they wrote, the impact it had, and the worthiness of their ideas. It’s far from the final word on any of these people, but a useful way of understanding what they were all about, at a time when understanding these economic giants is perhaps more important than ever.