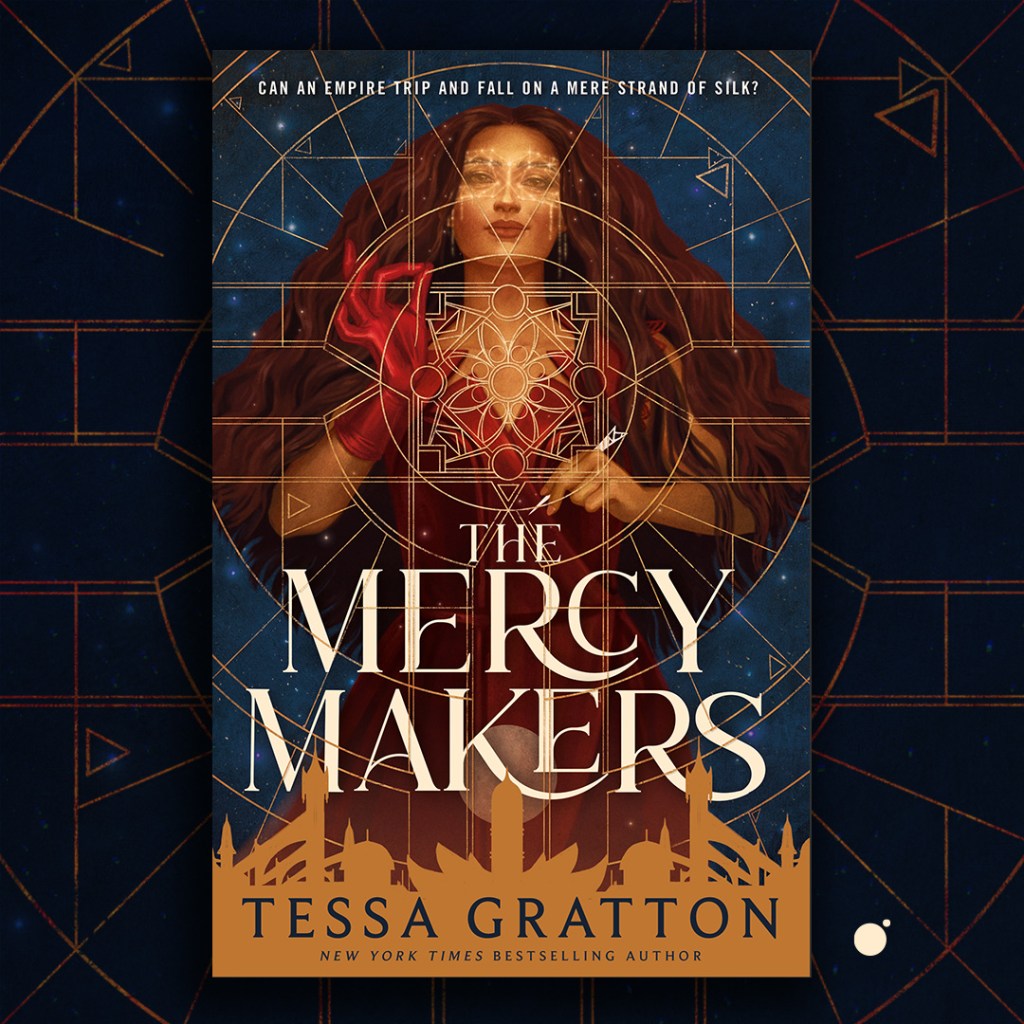

Excerpt: THE MERCY MAKERS by Tessa Gratton

A talented heretic must decide between the pursuit of forbidden magic, or the ecstasy of forbidden love, in the start of a sweeping, romantic epic fantasy trilogy by New York Times bestselling author Tessa Gratton.

Read an excerpt from The Mercy Makers (US), on sale June 17, below!

FALLING

Without Silence, there is nothing to break.

—Word of Aharté

1

Strand of silk

High above the sharp-edged palace of the Vertex Seal, the moon hangs motionless.

And far beneath it, a young god struggles.

There is a line in the sister works Word of Aharté and Writings of the Holy Syr that has been debated for nearly all the centuries since the two pamphlets were published. In Word of Aharté, the line reads: “My empire will fall on a strand of spider silk.” In Writings, the line is: “Can an empire trip and fall on a mere strand of silk?” The prophetic tone of the former stands out in the otherwise practical Word, while the irreverent humor of the latter is typical of Writings. What strikes scholar-priests most deeply is that both Aharté and the Holy Syr would comment so specifically on the same thing, but as if they disagreed on those very specifics.

It is not a translation issue, for both works were composed in pure mirané—the first known examples, in fact. Perhaps it is a conversation between the goddess and her wife that they continued in the pages. Though the Holy Syr explained so many of Aharté’s laws to us in her Writings, we are supposed to put faith in the goddess’s word over that of her wife, given that she is a goddess. But you know it is not spider silk that brings down the Vertex Seal. An alarum trembles through the glazed-brick walls of the hidden fortress of Isidor the Little Cat, but his daughter, Iriset mé Isidor, does not hear it.

Tucked down against the geometric tiles in her workshop, she carefully lifts her crystal stylus, drawing a line of force up from her planning vellum into the air. She holds her breath as she completes the connection of this corner line to the seventh squinch supporting the dome of the spell.

A prodigy at architectural design, she discovered by the age of thirteen how to disrupt the threads of force humming through the walls without the use of null wires, creating a workspace devoid of interference. It is convenient when building an intricate scale diagram for a new invention—much less so when under attack from soldiers of the Vertex Seal.

The delicate dome she’s building vibrates with ecstatic force, signaling she’s completed the internal structure correctly. Iriset releases her breath and smiles smugly, leaning back onto her bare heels. Sweat drips down her spine to the loincloth she wears to work; she prefers as much of her skin open to the air as possible, in order to feel the slightest change in the forces around her. The nape of her neck, inner wrists, and small of her back are particularly sensitive, and so, she’s recently discovered, are her lips. Her mask is folded beside her knee, along with her red robe, jacket wrap, and pantaloons.

The design diagram is beautiful.

Exquisite lines of shimmering silver architecture display the plan for a low, wide dome built of all four forces—rising, falling, ecstatic, and flow—that are the basic elements of her craft. The dome is meant to be settled over a small-scale model of Moonshadow City, and when connected to the Holy Design via illegal interface, it will reveal the places where architecture has shifted or changed since last the dome was applied, and therefore reveal where new security measures are set to capture her father.

Just in time for his birthday.

The door to her study jerks open. Hard alarum threads sweep inside, buzzing along the tile floor. Iriset shrieks and reaches out, trying to capture the alarm before it hits the first edge of the diagram, but her bare hands can’t grasp the threads. “Bittor!” she snaps as the structure collapses in upon itself, dome wavering first, then unraveling. “You always knock when I’m working! You know that! You…”

Her gaze meets the dilated cat-eyes of the man panting in the arched doorframe. There is blood on his face, and blood on his unsheathed sword.

The hairs on Iriset’s arms and neck and small of her back rise: the alarum! Now that the study is breached, she hears pounding chaos from the stairway beyond Bittor. A shock of fear freezes her in place on hands and knees.

Bittor charges inside. “Give me your silk glove,” he orders. In his left hand is a burning candle.

Iriset grabs her red robe and throws it over her head, then shoves her arms through the tight sleeves. Bittor never commands her! He has no right. “Why? What’s happened?”

Instead of answering, he stalks directly to the north curve of her study wall and puts the candle flame to the lowest of the layered orb webs.

The spiderwebs catch in a flash, curling in on themselves and drifting suddenly unattached from the white tile walls. She sees the fat-bottomed spiders scurrying for safety, but Bittor is faster, smashing them with the butt of his sword.

“What are you doing? Leave them alone!” Iriset yells.

“Your silk glove, now,” Bittor says, sparing her a fast glance before putting the flame to a cluster of scrolls and half-sketched diagrams piled upon a kneeler. “And put on the rest of your clothes! Get two floors up to the blue landing. The army has taken your father, and you cannot be found in here with the designs. Is your spider mask here?”

“Father…” she says, slowed down by the crisp smell of her work turning to ashes. Rising force fills the air, stifled by tarnishing smoke. A scream sounds outside the room, and a huge tremor shakes the tower. Iriset leaps for her low desk and grabs up the glove woven of spiderwebs and the finest worm silk. She clutches it to her chest, nails digging too roughly into the delicate material. It’s her greatest invention, and Bittor is setting her work on fire. Grief grabs at her when she looks at the smears on the wall: everything left of her poor spiders. They had names.

Bittor says, “Give it to me and go, Iriset.” He sweeps everything off her desk, kicks a floor pillow and raggedy braided rug into the pile, and drops the candle into it all. A smolder begins immediately.

Iriset stares at the disaster blossoming around her. There in the pile, knocked off her desk, is the glinting black spider mask. Fire reflects wildly the facets of the lower eyes. It won’t get hot enough to crack the chips of smoky quartz, but the glue will melt.

“Isidor said I should tell you, ‘Sign Amakis,’” Bittor says.

The code is a slap across her mouth. It’s her mother’s name, and by invoking it, Isidor invokes the bond Iriset swore when she turned seventeen, in order to remain in his court as an adult. She swore to protect herself above all else.

Bittor steps close and takes the silk glove. Then he kisses her. Surprise opens her mouth under his, and she gasps at his lips. Bittor rarely instigates. Quickly she puts her hands to his jaw and kisses back. It might be the last time, if the day doesn’t go well for them.

Though in the Little Cat’s court it is known they are friends, if not that they are lovers, outside Iriset and Bittor could easily be mistaken for born family: Both are colored like dark desert peaches, with pink lips and the square jaw of the Lapis Osahar dynasties. While her eyes are sandglass brown, Bittor has rare cat-eyes, with slit pupils and vivid sea-green-blue irises filling most of the space between his lids. Hundreds of years ago apostatical human architects designed the eyes for one of Bittor’s ancestors, and unlike most apostasy, this manipulation bred true through generations, popping up here and there. The Silent priests determined the children are at no fault for the apostasy of their ancestors and are thus allowed to live. But Bittor’s gaze is disconcerting to say the least. He doesn’t mind, as his eyes give him a boost as a night-thief and escape artist. Iriset has tried to examine them with her stylus when he is most relaxed, postcoital. Bittor says it’s one thing for her to seduce him in order to study his masculine-presenting body and how the four forces interplay within him during sex; it’s quite another for her to act like she’s eager to dissect him.

Bittor pushes away. He stares at her, pupils narrowing to slits as the fire grows behind her. “When they take you,” he orders, “make sure everyone knows you are the daughter of Isidor the Little Cat, and you won’t be harmed. Not by the Vertex Seal, not by your fellow prisoners.”

Iriset sets her teeth. Bittor is the Little Cat’s escape artist: He’ll have a way out. “Why can’t I go with you?”

“That isn’t his command,” Bittor says simply.

Nobody will go against her father except her. She says, “They have my father already?”

Bittor nods, and frowns beneath his thin beard. His voice is low as he says, “There is nothing you can do, and you can’t get down to the street. They are below us, on nearly every level, surrounding the whole Saltbath precinct, and brought with them investigator-designers who drove hard falling forces down through the streets in case we had tunnels. They knew, Iriset.” Darkness colors his cheeks and he bares his teeth helplessly.

“Someone betrayed us,” she says calmly. Too calmly.

Bittor ignores it. “Do not let them think you know what you know of design.”

“I know what I am bound to protect,” Iriset says. Herself. She’s not allowed to protect her father or Bittor, nor any of the cousins of the court. She must prioritize her own life, not claim her mask-name. She must allow fire to strip away all the evidence of her discoveries. Rising force inside Iriset lifts painfully, a yearning pressure.

Bittor kisses her again, and then pushes her toward the door. “Go, Iriset.”

Iriset snatches her clothes and red silk mask off the floor and obeys.

The air outside the study is cool with morning breezes from the windcatchers carved into every level of the tower, but that wind brings sounds of battle and desperation: steel clashing and cries of pain, the shaking of stone and ecstatic force. Iriset dashes to the wide spiral stairs up and up along the outer edge of the tower. Her bare toes hardly touch the limestone bricks, and her fingers skim along the smooth white stucco walls, until she spills up into the blue landing.

Untouched yet with violence, the landing is a small sitting area with two levels: one of perfect mosaic tiles in the shapes of blue gentians, the second layered with rugs and pillows in every shade of blue beside a huge lattice window spanning nearly half the entire curved wall. The glittering lattice snakes that usually wind through the cutouts, soaking in sunlight, are nowhere to be seen. Hiding, she hopes, sparing another brief thought for her poor dead spiders.

Iriset sits hard on the second level and pulls on her pantaloons, knotting them around her waist under her robe, and adjusts the laces at her ankles. She shoves her arms into the short jacket and ties it under her breasts, but loosely in case she needs to run or scream or fight. Finally, she pins the red silk mask to her hair, tucking it up so that a quick tug will let it fall over her eyes.

By now Iriset hears voices just below, methodical and ordered: soldiers searching the levels of the tower.

She stands. Through the soles of her feet she feels the tower’s architecture trip and startle. Fear disrupts her body’s design, an influx of ecstatic energy. She’s unused to being afraid under either name she’s used: Safe as Isidor’s daughter, coddled by murderers and thieves. Safe as Silk, too, thanks to her own skills and the Little Cat’s favor. Now Iriset needs to balance her inner design for calm. Fear serves nothing once its warning is made.

Hard boots clomp up the stairs to the landing.

She is Iriset mé Isidor, and even in his absence she will make her father proud.

Her father, so tough and sly he rules the Moonshadow City undermarket. He is slight and wiry, hardly larger than her, yet he commands respect through his reputation and deeds. He would not give Iriset sympathy, were he here, but snap at her to lift her chin and face the consequences of their choices with eyes clear. Wear her mask demurely, be what he needs her to be in that moment—a daughter sheltered and no threat to the empire. Keep her criminal identity secret. Survive what comes next so that she can make better, slyer choices in the future.

Just as the first soldier’s head appears in the well, Iriset jerks the red edge of her mask down. It brushes her nose and falls just to her lips.

The world turns hazy red as she peers through the thin silk.

The soldier’s own cloth mask wraps tight around their hair and face, leaving only a slit for their eyes, a blatant white that continues down in a uniform of lacquered armor over a short white robe and pants and thick boots: all clearly displaying the crimson splatter of their work. Their short sword is dark with smears of it. Behind them come more soldiers, identical in uniform and size, who stop around Iriset in a half ring. One says, in an impatient fem-forward voice, “Who are you, girl?” The speaker’s eyes are black, the slit of skin visible a darker brown than her companions’. None are the mirané brown of Moonshadow’s ruling ethnicity.

“Iriset mé Isidor,” she says boldly.

“The Little Cat has a daughter?” one of the other soldiers says.

Iriset doesn’t move.

The woman soldier darts a hand out and Iriset recoils, expecting a slap, but the woman only rips the mask off her face.

Anger flushes rising force up her spine, and Iriset struggles not to show it. If this woman will not give her the little respect of the mask, what else might be taken from her?

“Get her out of here,” the commanding soldier says, and her soldiers obey with grabbing, hard hands, dragging Iriset down the spiral stairs.

This is what Iriset does not know about the attack on the Little Cat’s tower: The city army of the Vertex Seal has been targeting her specifically for over a year. Or rather, targeting Silk.

Rumors of Silk’s existence have filtered through the gossip of the small kings of the Holy City for nearly seven years now. She is said to be a prodigy at design who invented a wondrous—and proprietary—material called craftsilk that every architect in Moonshadow would like to get their hands on. But Silk doesn’t share. She works exclusively for the Little Cat, and rumors accuse her of everything from creating design nets for cheating at cards to illegal human architecture that can disguise the features of Isidor’s thieves and spies so they can slip into the halls of power or infiltrate a rival’s bank. Some say Silk can cause a heart attack with a kiss of ecstatic force, others that she merely helps the Little Cat toy with his prey, using tricks of flow to keep a rival awake for questioning or wearing a mask of a Seal attendant’s face to whisper here and there, shifting the tides of scandal. Perhaps she is a rumor only, or an amalgam of several talented designers in the Little Cat’s employ. The latter opinion held the most favor for a while, until Silk herself began publishing brief, passionate papers that edged extremely near a pro-human-architecture stance. In the third paper she directly refuted the rumors she was several people.

But the city army has little evidence of anything other than that Silk is a woman. All they know is that since her appearance, the Little Cat has grown bolder in sending out his disciples. They scale towers like rock skinks and paint his graffiti for all to see, smuggle goods through blockades held by the city army, and hijack force-ribbons in order to stop traffic, jamming the schedules of the richest folk in Moonshadow for whatever no-doubt nefarious reason. And they never get caught. They leave only evidence they intend to leave.

Under the leadership of the Little Cat and his pet apostate, the undermarket has thrived.

While the Little Cat keeps his people to thieving, gambling, and smuggling, the occasional venture into fixing scandals or tugging small kings’ political strings—oh, and a few memorable murders—the recent growth has made many in the army concerned about how easy it would be for Isidor’s organization to turn to outright rebellion. And the Vertex Seal is always deeply concerned with rebellion.

Two years ago, apprehending Silk and her benefactor, Isidor the Little Cat, was declared a priority by the mirané council, with the backing of the Vertex Seal, Lyric méra Esmail His Glory. But for internecine mirané council reasons, the army has been denied their request for access to investigator-designers from the Great Schools of Architecture. Then some enterprising commander suggested they stop arguing for access based upon the crimes the Little Cat had been accused of—for what are such atrocities as murder and thieving to the Vertex Seal, which expands its imperial grip in ever-increasing waves through much the same? Lyric, however, is known for his piety and devotion to She Who Loves Silence, and so might not apostasy be an easier argument to make? Surely Lyric could be convinced of the likelihood that Silk had broken the goddess’s proscription against engaging in human architecture, not merely written of it. Apostasy, not atrocity, would spur him to action.

It worked. The zealous can be quite predictable.

No offense.

So the city army, the small kings who rule the various precincts of the city, and the Great Schools of Architecture bound themselves together in the chase. (The Great Schools argued for Silk to be taken alive, for their magisters are desperate with envy that an unknown, anonymous designer had learned to fashion the forces of architectural design into spells as fine as spider gossamer, when they themselves could not even replicate such workings. Ha!) This was an unheard-of alliance hunting Silk and the Little Cat, but an initially unsuccessful one, for the criminals slipped again and again through the army’s fingers.

Until a young designer with just the right combination of curiosity and ambition set ans mind to tracing Silk through less obvious means. Raia mér Omorose is just twenty-two and from a Pir-pale family of little means to buy ans way into a Great School or bribe any of the ranking designers to apprentice an directly. So Raia relied on ans wits and determination and no small skills at design to find other ways of promotion.

An charmed ans way into the possession of a scrap of a thin scarf Silk had created apparently to wrap around a thief’s face and work as a half-mask that would add a birthmark or beard to their jaw. It was, as suspected, dangerously close to human architecture. But it only hid the face of the person wearing it; no alteration took place. Carefully dissecting the threads of force—mostly flow for flexibility and ecstatic for the amazing adhesive qualities—Raia realized Silk was not imbuing her designs into actual spiderwebs alone any longer, if she ever had been so exclusive (she had), but strands of pure silk. Though an hardly could afford silk anself, ans brother had been recently married, and for the seed necklaces, Raia’s mother had purchased a small skein of raw silk from the Ceres Remnants. The silk had come already twisted into stronger threads of seven or ten strands, and cut shorter than this single long, nearly invisible strand woven through the designed scarf.

This led Raia to a startling epiphany: Silk was unspooling her own strands of silk from the cocoons of the worms. She—or someone on her behalf—was importing cocoons so that she could control every aspect of her material.

Although ans admiration for this mysterious woman’s ingenuity was veering toward a dangerously romantic swell in ans heart, Raia revealed the discovery to the investigator-designer in charge, since Raia anself did not have the resources to trace imports from the Remnants into the empire.

Thus, on day two of the Blossoming Contemplation quad—today—the army of the Vertex Seal surrounded a six-story tower in the Saltbath precinct. As the sun rose into a dawning sky the same purple of winter cacti, soldiers blasted through a beautiful arch of design security and attacked.

2

The Little Cat’s daughter

When Iriset was seven years old, her father brought her a three-legged bobcat kitten. How she’d adored the black tufts at its ears and its round green eyes, the large pads of its feet and long, fluffy tail. Its fur was colored like sand in the shadow of a drooping juniper, just like her father’s hair. She’d watched it learn to leap without stumbling, to play awkwardly with only three legs, and she’d designed it a pair of wings made of linen, her own hair, and long twigs of rolled vellum. In a slick work of genius, she married the wings to the kitten’s musculature so that it could control them, inventing a new sort of creature. The wings did not give flight to the desert cat, but helped it glide, helped it balance. They beat gently in the slightest breeze.

Her father was furious but did not yell, instead only took the bobcat kitten away and explained in plain terms that such design reeked of forbidden human architecture: No designer could attempt to create life of any sort, for life was the purview of the goddess alone. “Do you understand why the time before Aharté is called the Apostate Age?” he asked.

“Because architects could do whatever they wanted,” she complained.

Instead of laughing at her sass as he often did, Isidor’s mouth hardened. “I will have a collar of null wire fashioned for you if you do not appreciate the dangers of apostasy. Architects created wonders and they created monsters before the Glorious Vow. Not only the fragments that remain now—the skull sirens and micro-vultures—but chimeras, half-men, undead, unicorns, and flying whales capable of devouring entire families.” The Little Cat stopped talking, for he saw the thrill blossom in her gaze.

“Unicorns?” Iriset whispered.

He crouched and put his warm hands to her cheeks, staring into her eyes, and she stared right back. Her father’s eyes were gray and flecked brown, just like a Cloud King, and even then Iriset was wondering if she could design a window that looked exactly like them. She’d seen a dead man’s eyes once, when she snuck out of her bedroom in their old petal apartment. Her father had been conducting business he expected to be nonviolent, or it wouldn’t have happened where his wife and child slept. Iriset hadn’t witnessed the kill, but she’d stared at the blank eyes of the dead man, his head tilted toward her and blood all over the floor.

Though at seven she’d not yet designed her first craftmask, or even conceptualized it, she made the intuitive leap that it was not accuracy nor detail that would create the perfect illusion of life in a craftmask, but motion and reflection. Death was still. Life trembled with force.

“Iriset,” her father said gently, seeing her curiosity regarding the unicorn. “I was wrong. You do not have to understand. You simply have to obey. Do not turn your attention to human architecture, or anything that glances against it. If you do, I will collar you. That is my vow. Now it is your turn.”

She put her small peach-brown hands against his white cheeks so that they mirrored each other’s poses. “Did you kill the kitten?” Iriset asked.

“Yes.”

Ecstatic force crackled down her spine, a tremor she automatically breathed into balance with the flow of her heartbeat. It was fear, but not only fear: excitement, too. This topic mattered so much, it could kill. How could anything less dangerous signify? Iriset said carefully, “I will do as you command; that is my vow.”

Thus went her first bond, carefully worded to be bendable. She only ever blatantly broke it once, and never regretted the choice.

When Iriset was eleven and her mother recently gone, her father pulled her onto his lap on the slender throne in the basement of his first gambling den. Her lanky limbs sprawled everywhere, limp in her grief, and Isidor held her tightly, haggard in his own. He buried his nose in her knotted hair, holding her back-to-chest, and together they breathed.

“I understand what you are now,” Isidor said to his little daughter. Awe and fear tangled in his voice, but Iriset couldn’t read such things then. She only turned her face toward his neck to cry.

But Isidor caught her jaw in hand. He looked at her sticky lashes, the splotched peach of her cheeks, and saw her mother in the turn of her lips. “But, Iriset,” he said, “the Little Cat’s daughter cannot—must not—think or perform or even smell like human architecture.”

She blinked at him, and unlike the tone of his voice, she could read the tension in the tiny muscles around his eyes, the fear and concern and love set like a scaffold against the architecture of his face.

“Do you hear me, Iriset?” the Little Cat demanded.

“Yes,” she whispered. “I can’t be your daughter.”

Isidor’s mouth pressed down in displeasure. “No.”

He waited. He knew she’d get there without further hints.

Iriset tucked her head under his jaw. He allowed it. She tried again. “Iriset has to be innocent. I need someone to blame.”

“That’s better. Do you know why?”

“Even the Little Cat is afraid of apostasy,” she said dully, accurate and scathing in the way of children.

When Iriset was seventeen, the Little Cat held a winter feast. Iriset did not attend.

It was the third night after the Night of Deep Hunger, when the tilt of the world makes the moon go dark, and the people of Moonshadow City celebrate the Moon-Eater, that old red god whose hunger for She Who Loves Silence was so great he ate his own moon like an apple. Bitten to the core, it fell from the sky.

The Little Cat’s court had grown over the years, thanks to money from roving gambling dens, favors paid and favors owed, and not to mention the occasional murder-for-hire or excellent score. He smuggled already, too, but before Silk he only could use the methods used by every other ambitious undermarket cat. On this third night after the Night of Deep Hunger, the Little Cat offered a feast to his most loyal, to his associates and helpers and their husbands and cousins. This year it took place in a catacomb disguised to look deserted by all but the dead. Disguised with design, of course.

But just before midnight someone put one delicate crystal stylus to the design net and tore it down.

This person walked through the low stone hallways, following the shade-torches and graffiti, past crouching thieves and revelers in full-face masks. None stopped them, for everyone was invited if they could find the door.

The Little Cat held court at a table of polished geode, with less impressive tables scattered about the largest of this catacomb’s chambers. Force-lights clung to the carved red-rock ceiling, illuminating people in apple masks and cactus masks, masks like the starry sky and masks of feathers and alliraptor skin and plain canvas masks painted with the favored foods of the old red god. They ate, they drank, and they moved in subtle patterns around the Little Cat, who sat alone in his dark blue robes and a mask with yellow rays like the sun.

The stranger slid along the red stone, dragging streaks of black silk and purple muslin. This person had taken pains to disguise any form, hiding in the comfort of androgyny, dark hair knotted at the nape and a terrifying mask covering their features from crown of the head and dripping over the chin.

Shaped of black-glazed ceramic, the mask gleamed with shards of smoky quartz glued into six faceted eyes arrayed around the actual eyeholes, which were covered by sheer black silk.

The spider walked into the Little Cat’s feast, and the room fell quiet.

“What do you want?” the Little Cat asked, flicking a hand to clear the space.

The spider knelt. When she spoke it was in a feminine-forward voice, enticing and plain. “I have come to bargain my design skills with the Little Cat.”

“I already have designers.”

“Not like me,” she said, and snapped her fingers. A surge of woven ecstatic and flow forces lifted the strips of silk and muslin, and her outer robe flared out around her in eight long lines, like a spider’s legs. Like a black sun.

The Little Cat leaned forward. “What do you want in return?”

“A workshop.” Her voice behind the spider mask hooked up in amusement. “The best tools and supplies a small king’s money can buy.”

“Your costume is cute, but not enough.”

The woman stood and raised her hands slowly to remove the eight-eyed mask.

Gasps stuck in throats, and the Little Cat’s court shied away.

Under the mask was the face of the Little Cat himself.

He removed his own sun mask, tossing it away.

Upon comparison, the spider looked a little more like his baby brother, or little sister. The jaw was not quite correct, the wrinkles too smooth, the nose a little too short. But it was close. Close enough.

Whispers of fear slithered through the catacomb. Whispers—and awe.

The Little Cat laughed, then reined in his knowing stare.

The spider grinned. “Imagine what I could do if I’d had a chance to be really close to you, study your structures, your expressions.”

“I’d rather not,” the Little Cat drawled. “Tell me your name, and I’ll give you a trial run.”

“Silk,” she said, and covered her eyes—her eyes that looked just like the Little Cat’s—to bow.

Even in the palace of the Vertex Seal, they heard the story of how the Little Cat found his apostate.

Meanwhile, the Little Cat’s daughter grew up to be gentle and pretty, with a quick wit when she chose to engage with her father’s people, and a wry smile when she did not. She wore simple cloth masks like the workers in her local Saltbath precinct and occasionally appeared at the undermarket court to serve her father coffee or rice wine imported (smuggled) from the southeastern territories of the empire. Iriset mé Isidor spent most of her time studying and running her father’s household, visiting her grandparents on her mother’s side, and sometimes wandering the Saltbath markets. She was quiet and rarely seen, and her grandmother hoped she would take an interest in mechanics, but Iriset tended toward more scholarly pursuits. She always brought her grandmother trinkets and her grandfather the night-blooming hothouse flowers her mother had adored. She knew the names of every shopkeeper on their street, and several for many petals in every direction. At least, that’s what people said about her.

They knew her mother had married a smuggler—a trader when people felt generous—and that Iriset remained at his side when Amakis died. As Isidor’s reputation grew, Iriset was seen less frequently on the streets, and she only visited her grandparents every few weeks. There was gossip she was being courted by a charming young Osahar boy but that he worked for the Little Cat and surely couldn’t provide a stable home. Sometimes a baker or mechanic on her grandmother’s row tried to tempt Iriset away from her father’s life of crime, but she always smiled and said her father was good, and the life she had was good. Besides, if her father was a criminal, wouldn’t he have been arrested already?

If people thought her naive, all the better. Though if they found her too innocent, that was bad, for the last thing she wanted was anyone trying to rescue her. The delicate tension kept a mind like Iriset’s engaged in the game.

At seventeen she began arranging flowers in her grand-uncle’s flower shop once a week, and let people know she was no criminal, but if they needed the Little Cat, perhaps she could pass a message. Iriset has always loved flowers, and loves the art of arranging them into bouquets. The balance of asymmetry and beauty might seem plain and innocent, but it feeds her unruly imagination.

If she wonders at the shape of leaves that turn toward the sun, or the exact number of petals on a mum and the curve of a thorn, if those thoughts lead her down long spirals of theory and potential, who is to know? All to be seen is the elegant arrangement of ghost lily and weeping spine fig and burst of scarlet moonflower.

See?

Sure, there is an apostate working for Isidor the Little Cat. A friend, lover, sister, bond… Who knows? But not his daughter.

The daughter of the Little Cat is no threat to anyone.

3

Prison

The soldiers of the Vertex Seal take Iriset to the apostate’s prison at the edge of the Crystal Desert in the center of Moonshadow City. She knows, because even trapped inside a ribbon skiff with null wires circling her neck and wrists to bar her from manipulating external forces, she can trace their path through the streets using her other senses and extensive memorization of the map of the city. Her father used to make a game of it every morning over breakfast. The better to avoid authorities and locate safe houses, the Little Cat said. The better to understand the security habits of the royal architects, Iriset answered. Both were true, of course.

In these days, Moonshadow City is the heart of the empire, literally and metaphorically. Moonshadow, the Holy City, glimmers inside a massive red-rock crater eight miles across. From the central palace complex built like succulents with sharp-edged leaves, the city unfurls with exacting Design: Sixteen precincts divide it into four quadrants, each ruled by the four forces of rising, flow, falling, and ecstatic. Brilliant white towers with star crowns and needle roofs poke up among vivid blue and green domes. Petal-style housing complexes spiral and curve like stucco roses in which people live and work. Peristyle halls frame green space to create temples to Silence, and there are gardens of lush rainforest plants, gardens of sand and glass, and water gardens filled with mirror fish and black lotus. Elegant force-bridges sweep across avenues and canals, humming with the hollow song of skull sirens, those tiny birdlike creatures from the Apostate Age that feed on the layers of rising and falling forces woven together to keep the bridges active. Dominating the skyline are the four Great Steeples in the north, south, east, and west that anchor the forces of the city, rising tall enough to cast thick shadows across multiple precincts.

The edge of the crater in the south glints with glass from the windows of pocket apartments cut into the red rocks, and the western cliffs are taken up by barracks shared between armies. The eastern crater face is terraced with gardens and walking paths and chapels, while the north is reserved for catacombs piercing deep into the earth.

The Lapis River passes into the crater via underground caverns, bursting up near the Rising Steeple to pour south and cup the city with its flow. Two sprawling canyons slice through the city, mirroring each other though they are on opposite sides of the crater: They are left over from experiments during the Apostate Age to draw water up from deep in the earth. People carved homes into the sides of the canyons, which flood in the rains and dry to dust during the Days of Mercy.

It is the most beautiful city in the world.

And above it, Aharté’s silver-pink moon hangs like a pearl affixed to the brocade of the sky.

Iriset’s cell consists of design-resistant walls and floor, empty but for a sleeping shelf and a clay bowl for relief. Once a day she’s fed soda bread and nutty cheese with a shallow bowl of water. The soldiers do not remove the null wires around her wrists and neck.

She paces the dirt floor, walking the lines of a four-point star, then eight-, then sixteen-point. The room is too small for thirty-two points so of course she convinces herself that nothing will relax her but thirty-two points. How is she to calm down without being able to sense forces thanks to the fucking null wires? Only walking patterns, only the repetition, and she needs the complexity of thirty-two. Her heart won’t stop pounding, she feels feverish and lightheaded, working herself into an intense state of anxiety until she finally falls asleep.

Iriset is unused to idleness.

The best she can do to distract herself is mentally indulging in wild theories of flight, which she’s never forgotten as she’s never forgotten the bobcat kitten. It’s her favorite architectural problem to chew on, and her theories have moved away from wings over the years: Some spiders, when young, build delicate gossamer webs with which to catch the wind, ballooning up into the air to travel miles and miles to new lands, new homes. She thinks perhaps that is a key to flight that doesn’t smack of creating new life. But the mathematics are impossibly complex, to heft a human woman’s weight on a thread of force, considering wind vectors and tensile strength and how to combat—or use, or use!—the falling force always dragging downward to the earth.

She wishes she had writing materials, or even just the company of her poor darling spinners, burned and smashed in her study. She misses the shiver of their tiny feet on her forearm, each step a shock of ecstatic force. She wants Bittor to crouch beside her, tell her he didn’t kill them, then wrap arms around her to ground her in her body. They spent hours testing force-reactions on each other: a bite here, a lick there, tickling the elbow or under the wrist, finding ways to draw out the rising force of desire. Iriset took notes comparing their bodies’ reactions, how Bittor’s masculine-forward design conveyed physical reactions to ecstatic force differently from hers. They made so many innuendos about rising force and flow.

(That was the essay that revealed Silk was a woman, when she included personal observations about pleasure in a feminine-forward body and theories about using the forces generated during sex to trigger delay-releasing medicines or poisons. Her father read it, as he read all her work, and told her to stop experimenting on his best escape artist. Raia mér Omorose read it in secret, and thought about Silk touching an tenderly, transforming ans body to a better gender. Bittor read it, too, and was so embarrassed he didn’t speak to Iriset for days and never read one of her pamphlets again.)

By the fourth day in prison Iriset’s robe is filthy, her mask balled up with her jacket like a pillow upon the shelf. Pale stucco dust sticks in the creases of her skin, and her fingernails are cracked to the quick from scrabbling to sketch equations upon the floor.

Halfway through the day, the cell door unlocks, surprising her onto her feet: She only has time to smooth hair off her face and wish she’d spent the moment grabbing her mask before two soldiers grasp her elbows and haul her from the cell. The stucco-smooth hallways wind upward, and they shove her into a room flooded with sunlight. Iriset winces away.

Her bare toes warm against a plain black-and-white geometric rug. There’s a long table at the center of the room, and a lattice window allows in blue sky, fractured sunlight. Beside it stands a young person in the simple tight robe of a palace architect. She assumes an is a man, which is the point of ans carriage and masc-forward clothes.

It is Raia mér Omorose, who earned a place with the palace designers for locating Silk. An makes a noise of distress and points to a bowl and pitcher at the corner of the table, and a pile of folded blue cloth. “Take a moment, please, to steady and drink, and change if you would,” an says, and leaves her alone.

Iriset tears out of her dirty clothes. Instead of using the bowl for gentle washing, she pours water straight from the pitcher onto her chest, swiping under arms and breasts, between her legs and then down her back. She tips her head upside down and does what little she can to scrub at her scalp. She needs a pick for the tangles, or to chop it all off.

When the pitcher is empty of every drop, she pulls apart the pile of clothes to find the mask first, which is a cloth mask, typical of the lower classes and first-generation citizens. With it, Iriset twists up her heavy hair, winding the plain linen across her forehead and under her chin, securing it all firmly, with a fluttering edge by her ear to hide her eyes if she needs it. Only then does she find the robe and loincloth and vest. Having her hair wrapped again is such a relief she almost laughs, longing for the luxury of a few moments to stand nude atop the table, free of null wires, to feel for errant threads of ecstatic or rising force.

The gentle knock and long pause before the door opens again are an unexpected kindness that relaxes her slightly as she positions herself beside the lattice window where she can feel a breeze on her cheek, if not the omnipresent hum of force-ribbons outside.

Raia immediately touches ans fingers to ans eyelids. It’s polite, a gesture of respect for the goddess Aharté, who prefers her children not to share the intimacy of long eye contact unless they’re family or otherwise bound—it is also an old tradition against human architecture. If you show your eyes to none, none can design a mask of your face. That’s why the masks, too. An old tradition—or superstition, Iriset might say—born with the mirané people.

Iriset touches her eyelids briefly in return. She does not draw the mask across her sight.

“I am named Raia mér Omorose,” an says.

Before she can help it, Iriset smiles at the descent indicator Raia uses in ans name, which reveals ans preferred gender. Alternative genders are not forbidden under Silence, but they are certainly discouraged. Raia smiles back tentatively. Ans mask is only face paint, as is typical of architects and also in fashion with the miran these days. Architects dislike masks of cloth, leather, or particular ceramics for how they might interfere with intricate design. But most body paint is mixed to be architecturally neutral. Raia wears jagged stripes of black—the color of flow—painted down over ans eyelids and narrow cheeks. Ans hair is straight brown-black and skin Pir-pale. There is little mirané blood in the shape of ans nose and brow, though ans cheek- and jawbones are very symmetrical and therefore more difficult to draw, but easier to create a craftmask for. An wears no beard (of course an could not without the aid of apostasy), further marking an apart from the miran, for whom it is in fashion to cut their beards in patterns to match their masks and face paint. An is young to be interrogating Iriset.

She realizes, as she catalogs information, that she’s staring with Silk’s eyes, practiced in memorizing bone patterns and gender-design details, not with the gaze of the modest daughter of a famous thief. She immediately draws the cloth mask across her face.

“Are you Iriset mé Isidor?” Raia mér Omorose continues, as behind an two more people arrive. The man—judging by his masculine-forward design—has a tightly curled beard and a military mask of white leather flat across his forehead that curves like scythes down over his cheeks, cupping his eyes but not at all obscuring his vision. His heavy brow lowers into a glare at Iriset. His skin is mirané brown, lined with fine wrinkles, and he wears the white robe, leather vest, and weapon sash of the city army. The woman hurries in, cloth-masked and robed in plain linens. She puts a box on the table and leaves, dragging the door closed behind her.

Raia doesn’t introduce the glowering soldier, but opens the long box and begins laying out items from it.

A design stylus.

A pair of delicate forceps.

One-half of wire moth wings.

Iriset’s own white silk glove, with a dot of dry blood atop the thumb. The one she gave to Bittor.

He would have planted it on Paser or Dalal, Isidor’s other designers, to help one of them take the fall as Silk. Iriset hates the thought of another getting credit for her work nearly as much as she hates the idea of another dying for her.

“Do you know the glove?” Raia asks.

“Where did you get it?” Iriset asks in return. “Where is my father? I want to see him.”

The older soldier snorts. “We got it off Silk, of course.”

“Alive?”

“For now.”

Iriset stares at the spot of blood, wishing she knew who had taken her mask-name and is probably taking her punishment. She can’t ask without giving away the game. “And my father?”

“He’s still alive, too, Iriset,” the architect says, “and if you cooperate it’s more likely you’ll be granted a few moments with him before his trial.”

She inhales with a hiss. “Yes, I know the glove. So?”

“Do you know how she made it?”

Suddenly Iriset thinks of a way to claim some of her design without ruining the sacrifices her father’s people had made for her, without disobeying his command. “She allowed me to assist sometimes,” she says, leaning toward the glove. “I spooled the silk for her, and held it because my fingers are small, and that helped her.”

“So you aided in the illegal activities. In apostasy,” the older soldier says, with a satisfied but angry press of his lips.

Raia interrupts, “I’m not interested in that, Iriset. You have not been named as a criminal, nor shall you be if I can stop it. We need your help, though, to understand how Silk did what she did and in order to bring in any of her remaining designs and find ways to work against them.”

“No.”

“I only wish to understand,” Raia says eagerly. “I’ve studied what I can of Silk’s work, and it is genius. What she’s done could help so many people if it was turned away from thieving and illegal practices, and toward the greater purposes of architecture.”

Iriset holds herself still, angry pride in her heart because she knows what her craft could do; she longs for it.

Raia continues, “Imagine the more flexible building materials Silk’s research could help us develop, or security nets. Alarms and fiber glassworks, stronger ropes and suspension architecture for better bridges.”

“Oh.” Surprised into meeting ans excited gaze through the shimmer of her borrowed mask, Iriset realizes an isn’t lying about what an wants. Raia mér Omorose is a designer like Iriset, who sees possibilities. How can she use it? Can she trade it for a chance at saving her father’s life, or Bittor’s, or any or all of them? Pretend the Little Cat’s daughter is Silk’s innocent apprentice, and get what she needs?

The older soldier says, “And you’ll tell us what you know of Isidor Little Cat’s business, names, meetings, everything you remember.”

Iriset snaps her mouth closed. She dislikes her father’s name in his mouth. Little Cat is a sweet diminutive to hide the vicious truth, a palatable euphemism, but when the old soldier says it, the words flow with disgust.

“That’s the deal, child,” the soldier says. “Raia mér Omorose and I come together. He wants your magical knowledge, but I require practical information first.”

Raia flattens ans mouth but does not naysay the soldier.

Iriset forces her eyes to lower and lies, “I do not know any details about my father’s business.”

The soldier, who so rudely has not named himself, comes around the table and she backs away, knocking her heels into the stucco and her shoulder into the lattice window. He stops himself a breath away, overwhelming Iriset with his size and steely silver smell. His eyes are half-circles and hold flecks of green among the mirané brown; his long, tightly curled beard nearly brushes her chin. “If you do not agree, you will remain in prison and be sent to a work camp eventually, do you understand? Your sheltered daughter’s life will not stand up to the camps, and will not help you break limestone or plow the delta.”

“He is my father,” Iriset says.

“Do you think even a man like the Little Cat would see his daughter so abused for his own sake? Violent criminals and prisoners of war and the petty thieves or innocent who end up there are not separated, child. The Seal laws do not hold well in the camps, where wardens and guards have too much else to do than to make sure no young girls or skinny boys are being raped.”

“Bey!” Raia cries, aghast and hurrying to put anself between them.

The old soldier—Bey—remains expressionless. “She is the Little Cat’s daughter, Raia, and surely cannot be shocked by the mere mention of murder or assault.”

Iriset says, “You do not make me want to betray my father with this theater.”

“Good.” Raia touches her shoulder. “Fear only pushes us to act irrationally,” an says more to Bey.

“The name of the Little Cat will protect me wherever you put me, except from animals like yourself,” she says.

Bey the soldier smiles grimly. “I told you, Raia mér Omorose, that she was one of them.”

The architect ignores him, turning fully to Iriset. “I know you love the design; I saw it shine even through your mask, Iriset. That is what I am interested in: architecture and its secrets. What would we design for love of the work? If you agree, I will find a way to speak with you again.”

Iriset looks past Raia to where Bey shakes his head once for her. She understands: The architect is not in command here, though perhaps an naively believes an holds the power. But Iriset understands something else, too, about Bey’s inner design: He will be brutal with the truth, but he will not lie. If he were willing to lie, he’d have agreed with Raia to manipulate her.

“I agree,” she says to Raia, though she doubts it matters.

Iriset does love the work of design. But the only time she ever designed for love, it was the worst kind of apostasy: She cut into a human body to redesign malignancy. To heal. To save. Imagine the widespread application of that discovery—twelve years gone! How many dead might live today had she been allowed to breathe a word of her success? Given the chance, she could cure apostatical cancer. Start by pulling apart a miran to compare their design with that of any other of the empire’s ethnicities more susceptible to the mutation. It might be that miran do not know such diseases because they were designed by the hand of Aharté herself, from her flesh, but Iriset thinks it safer to study and be sure. Next she might discover the stoppage of flow that causes squared arteries in the older architects, or invent a night-vision applicator based on the design of Bittor’s eyes, or dig into a brain and root out the source of nightmares. Retro-design the skull sirens to determine how and why their skulls push out through their faces as they mature, and how they survive it. Interrogate the design-root of consciousness! Pinpoint the triggers for aging or miscarriage!

She understands why chimeras and certain kinds of human architecture and chemistry are dangerous, but not healing and refinement. Humans are intricate design and is it not our right to understand ourselves?

When someone suggested to her once that merely thinking such thoughts went against Silence, Silk said, “Wasn’t I, after all, designed by the goddess? If Aharté did not wish me to seek transformation, why design me with this desire?”

You see, Iriset was always destined to break the world.

★ “Laced with a vivid sensuality.” —Jacqueline Carey, New York Times bestselling author of Kushiel’s Dart

Can an empire trip and fall on a mere strand of silk?

Iriset is a prodigy and an outlaw. The daughter of a powerful criminal, she dons her alter ego Silk to create magical disguises for those in her father’s organization, but she longs to do more with her talent: to enhance what it means to be human by giving people wings, night-sight, and other abilities; to unlock the possibilities of gender and parenthood; to cure disease and even to end mortality itself.

Everything changes when her father is captured and sentenced to death. To save him, Iriset must infiltrate the palace and the empire’s fanatical ruling family. There, she realizes she has a chance—and an obligation—to bring down the entire corrupt system. She’ll have to entangle herself in the lives of the emperor and his sister, getting them to trust and even to love her.

But love is a two-way street, and Iriset’s own heart holds the most mysterious and impenetrable magic of all.

★ “Beautiful, elegant, passionate novel. A triumph and a delight from start to finish.” —Antonia Hodgson, author of The Raven Scholar

★ “Sexy and intriguing.” —Ellen Kushner, author of Swordspoint