By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

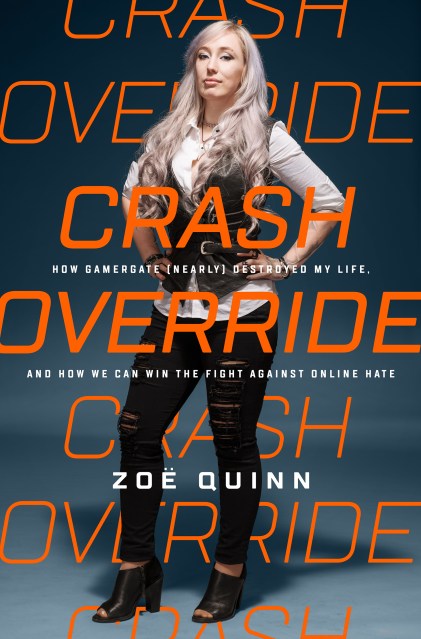

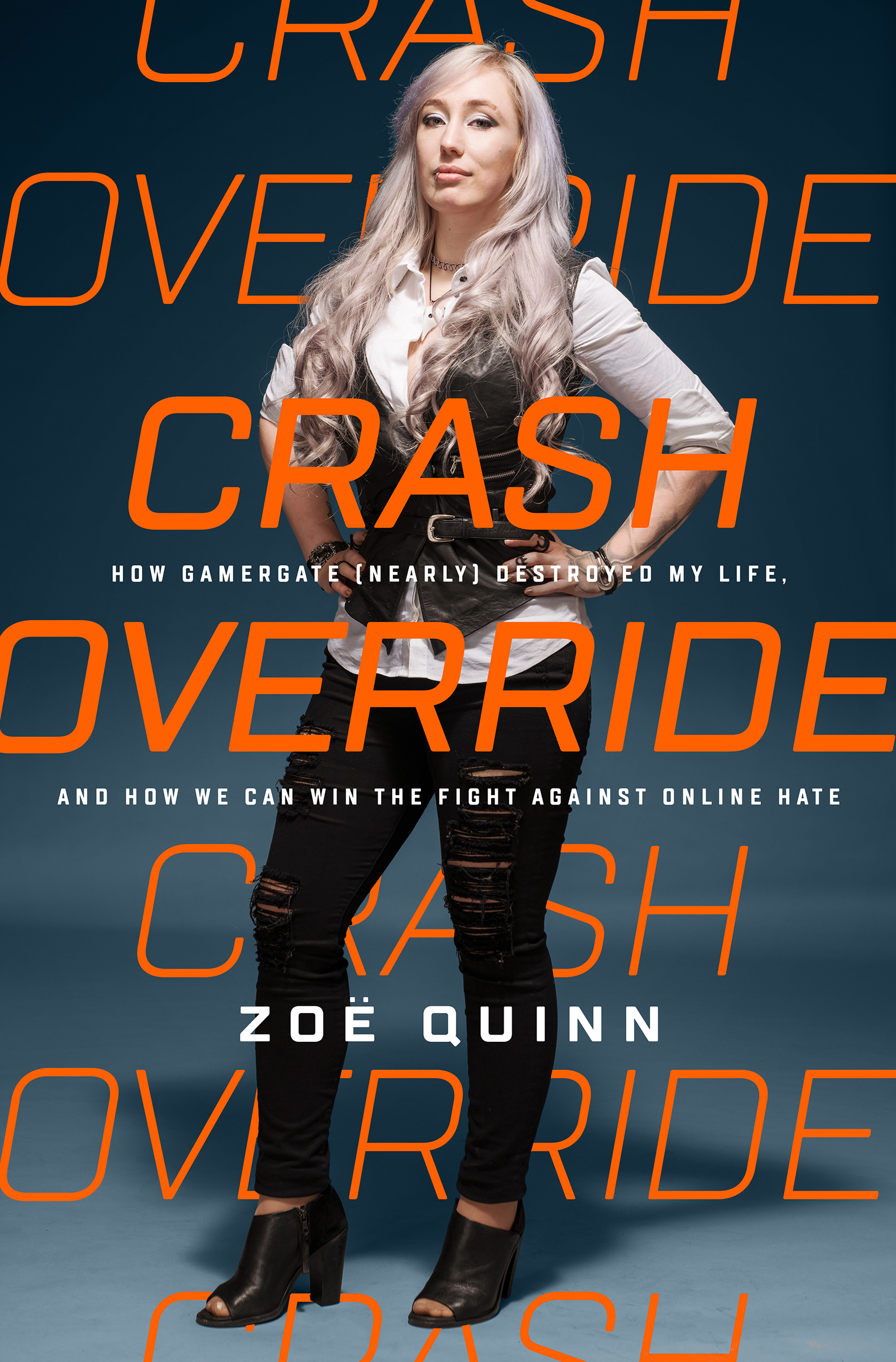

Crash Override

How Gamergate (Nearly) Destroyed My Life, and How We Can Win the Fight Against Online Hate

Contributors

By Zoë Quinn

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 5, 2017

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610398091

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 5, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Zoe Quinn used to feel the same way. She is a video game developer whose ex-boyfriend published a crazed blog post cobbled together from private information, half-truths, and outright fictions, along with a rallying cry to the online hordes to go after her. They answered in the form of a so-called movement known as #gamergate–they hacked her accounts; stole nude photos of her; harassed her family, friends, and colleagues; and threatened to rape and murder her. But instead of shrinking into silence as the online mobs wanted her to, she raised her voice and spoke out against this vicious online culture and for making the internet a safer place for everyone.

In the years since #gamergate, Quinn has helped thousands of people with her advocacy and online-abuse crisis resource Crash Override Network. From locking down victims’ personal accounts to working with tech companies and lawmakers to inform policy, she has firsthand knowledge about every angle of online abuse, what powerful institutions are (and aren’t) doing about it, and how we can protect our digital spaces and selves.

Crash Override offers an up-close look inside the controversy, threats, and social and cultural battles that started in the far corners of the internet and have since permeated our online lives. Through her story — as target and as activist — Quinn provides a human look at the ways the internet impacts our lives and culture, along with practical advice for keeping yourself and others safe online.

-

"A worthwhile read for anyone interested in taking action against the realities-and devastating effects-of extreme internet trolling...an informative and inspiring book."Kirkus Reviews

-

"I tore through this book. Zoe Quinn doesn't just present a clear-eyed examination of the internet's endemic sickness (though she does that beautifully), she contextualizes her personal nightmare within our current national one. It's a gripping read with historical merit."Lindy West, author of Shrill

-

"We finally have a chance to hear what we've been eagerly awaiting: Zoe's real story in her own words. If you've been harassed, depressed, lonely, or lost, her story will inspire and empower you. After all of it, she still finds a way to be optimistic and a force for positive change. She gives me hope for humanity and the future of technology."Ellen Pao, former CEO of Reddit, co-founder of Project Include

-

"At every turn, Zoe Quinn was utterly failed by the law enforcement agencies she counted on to protect her, and the social media companies that enabled her attackers. But she never gave up, refused to be a victim, and has used her experience to help countless victims of online stalking and harassment protect themselves. And she does it all with disarming humor and bracing honesty."Wil Wheaton, actor, producer, author

-

"Zoe Quinn captures the irrational contours of the #gamergate experience in vivid detail and offers a compelling personal history of the woman with a bullseye on her back."Anita Sarkeesian, founder of Feminist Frequency

-

"As the first target of the so-called #gamergate movement, and someone who fought it and won, Zoe Quinn is uniquely qualified to write this story. Think of this as Jon Ronson's So You've Been Publicly Shamed written from inside the eye of the storm."Graham Linehan, writer and director of The IT Crowd

-

"Part memoir, part social movement manifesto, this engrossing journey by game designer Quinn takes readers into the darkest realms of social media and the Internet.... An important purchase that will interest social media users and enlighten them about the extent of online hate in some social platforms and the limits on personal and social protections available in society today."Library Journal

-

"Quinn uses her personal experiences to advocate practical steps toward creating a safe and open internet culture.... For Quinn, winning the 'cultural battle for the web' starts with reframing the issue as not a matter of good vs. bad people fueling hate culture on the internet, but rather 'acceptable and unacceptable ways to treat each other.' It's a remarkably clear-eyed view that's all the more powerful in light of Quinn's backstory."Publisher's Weekly, starred review

-

"The overwhelming message of Crash Override resonates across industries and experiences: When someone disagrees with you on the internet, you shouldn't have to go into hiding."Latoya Peterson, NPR.org

-

"Crash Override combines a brisk pace, candid stories, and embedded insight. Quinn's first book has its uneven moments, but it's important stuff for anybody interested in how online discourse has shifted over the past two decades."Ars Technica

-

"Engaging and powerful...In Crash Override, Quinn proves to be a thoughtful, accessible guide through this social, cultural, technological and political morass."Toronto Globe & Mail

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use