By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

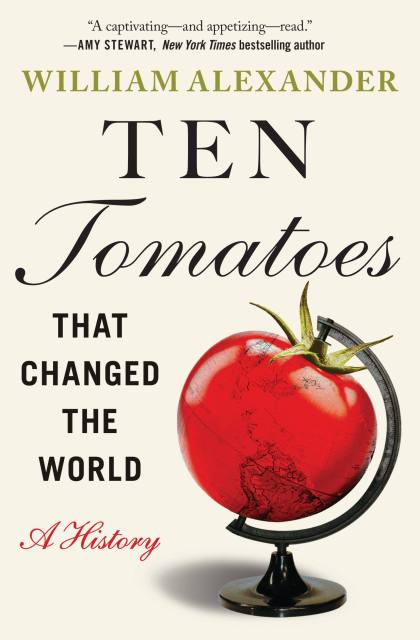

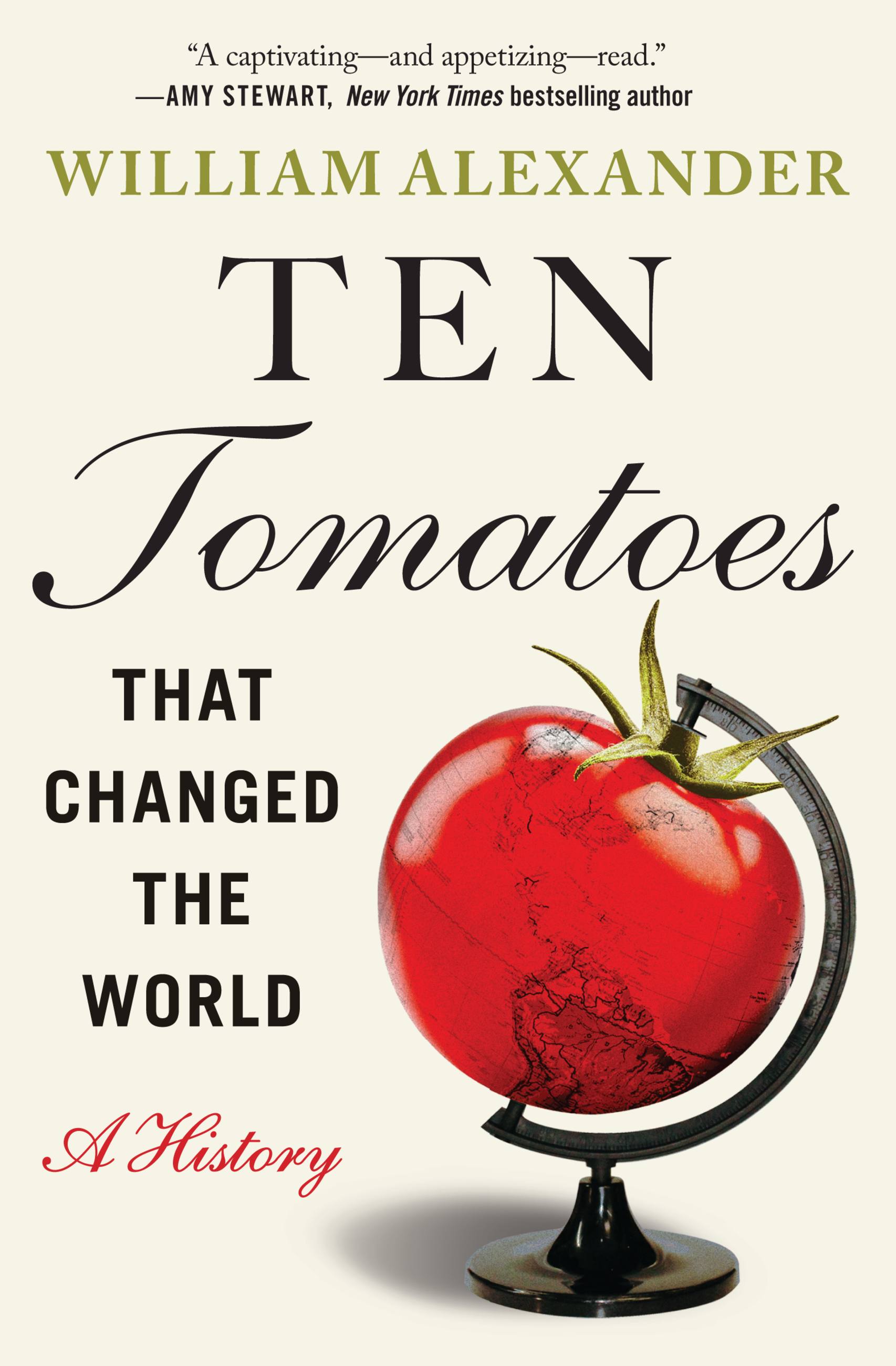

Ten Tomatoes that Changed the World

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 7, 2022

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538753316

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 7, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The tomato gets no respect. Never has. Stored in the dustbin of history for centuries, accused of being vile and poisonous, appropriated as wartime propaganda, subjected to being picked hard-green and gassed, even used as a projectile, the poor tomato is the Rodney Dangerfield of foods. Yet, the tomato is the most popular vegetable in America (and, in fact, the world). It holds a place in America's soul like no other vegetable, and few other foods. Each summer, tomato festivals crop up across the country; John Denver had a hit single titled "homegrown Tomatoes;" and the Heinz tomato ketchup bottle, instantly recognizable, is in the Smithsonian.

Author William Alexander is on a mission to get tomatoes the respect they deserve. Supported by meticulous research but told in a lively, accessible voice, Ten Tomatoes that Changed the World will seamlessly weave travel, history, humor, and a little adventure (and misadventure) to follow the tomato's trail through history. A fascinating story complete with heroes, con artists, conquistadors and, no surprise, the Mafia, this book is a mouth-watering, informative, and entertaining guide to the good that has captured our hearts for generations.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use