Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

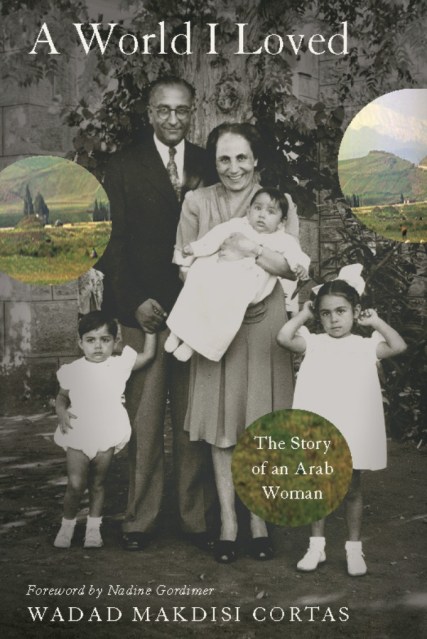

A World I Loved

The Story of an Arab Woman

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 12, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Through Cortas’ eyes we experience life in Lebanon under the oppressive French mandate, and her desire to forge an Arab identity based on religious tolerance. We learn of her dedication to the education of women, and the difficulties that she overcomes to become the principal of a school in Lebanon. And in final, heartbreaking detail, we watch as her world becomes rent by the “Palestine question,” Western interference, and civil war.

The World I Loved is both an elegy on Lebanon and her people, and the unforgettable story of one woman’s journey from hope to sorrow as she bears painful witness to the undoing of her beloved country by sectarian and religious division.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 12, 2009

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780786744619

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use