By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

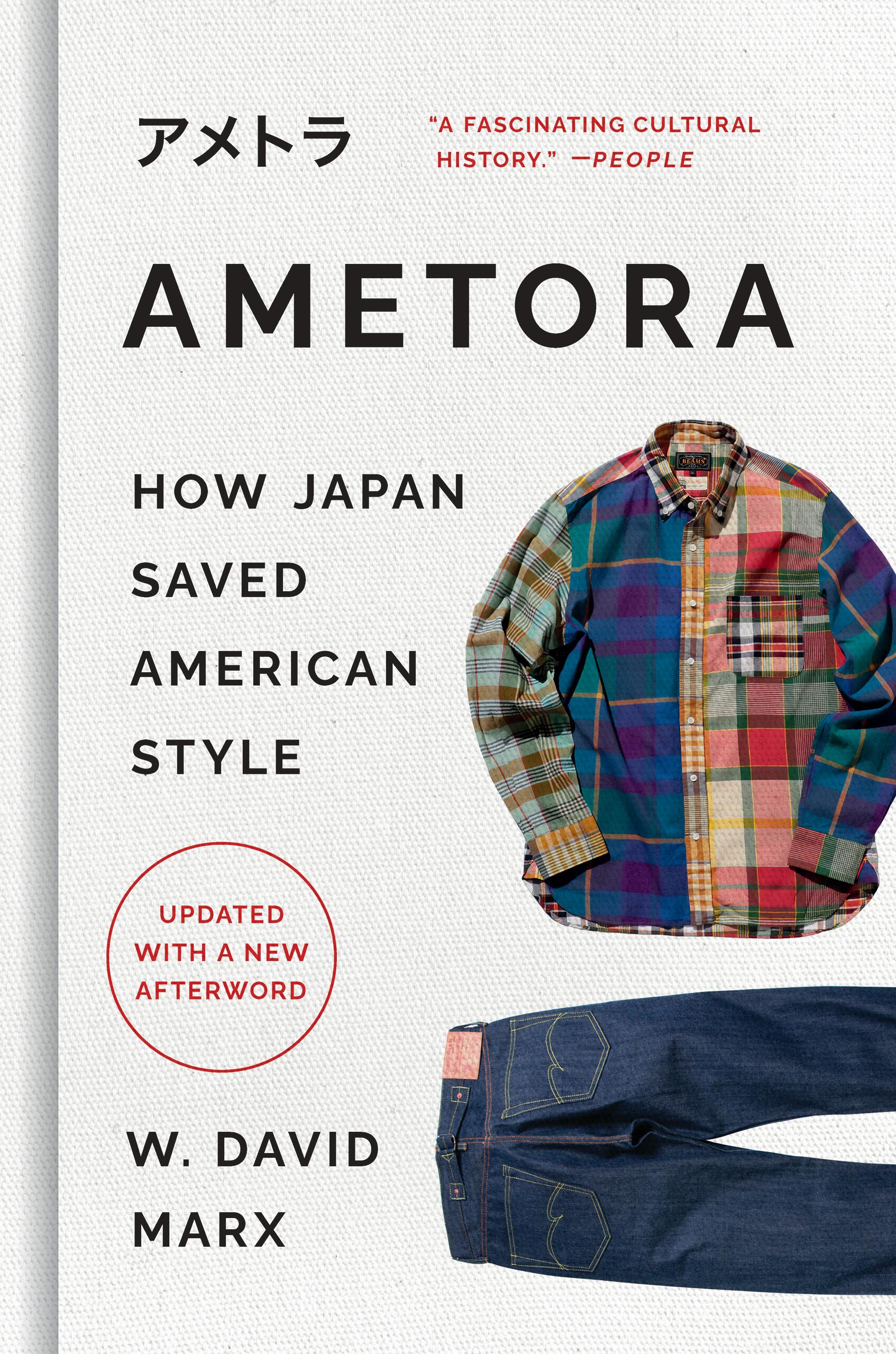

Ametora

How Japan Saved American Style

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 26, 2023

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541604339

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $18.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 26, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“A fascinating cultural history.” —People

A strange thing has happened over the last two decades: the world has come to believe that the most “authentic” American garments are those made in Japan. From high-end denim to oxford button-downs, Japanese brands such as UNIQLO, Kamakura Shirts, Beams, and Kapital have built their global businesses by creating the highest-quality versions of classic American casual garments—a style known in Japan as ametora, or “American traditional.”

In Ametora, cultural historian W. David Marx traces the Japanese assimilation of American fashion over the past 150 years. Now updated with a new afterword covering the last decade, Ametora shows how Japanese trendsetters and entrepreneurs mimicked, adapted, imported, and ultimately perfected American style, dramatically reshaping not only Japan’s culture but also our own.

-

"Japan's exalted status in the fashion department seems like a given now--even non-sartorially inclined folks likely know Japanese brands like Comme des Garçons and Uniqlo or could recognize the trendy look of the Harajuku neighborhood. But perhaps less well-known is the fascinating decades-long dialogue between American and Japanese men's fashion that Marx skillfully explores here.... It's riveting to follow as men swap their austere student uniforms from Japan's imperialist days for chicer garb, no longer ashamed to care about style.Entertainment Weekly

-

"You'd be wise to put Ametora at the top of your 2016 style reading list."San Francisco Chronicle

-

"A fascinating cultural history."People

-

"Ametora by W. David Marx traces the craze for American fashion after World War II in Japan, but it quickly becomes larger than that. It's a fascinating window into how fashion, culture and history intersect; you end up learning about several things at once."B.J. Novak, Wall Street Journal, one of the best books of the year

-

"Mr. Marx writes with the understanding of how rich his material is. The scenes and the style trends in his book are not only interesting but often absurd."Wall Street Journal

-

"A fascinating, finely-observed, highly readable history of the wonderfully unlikely rescue of iconic 20th Century American menswear by the Japanese who loved it when we no longer did. I had of course been aware that this had happened, but had never expected to see it reconstructed by a cultural historian of W. David Marx's very evident skill."William Gibson, author of Neuromancer and The Peripheral

-

"W. David Marx is our most insightful observer of the pop culture traffic between Japan and the U.S.A. Focused on fashion, Ametora tells the fascinating, intricate story of how Japan--the most style-obsessed country on earth--has beaten America at its own game, in the process established itself as the world's leading nation for curation, simulation, and mutation."Simon Reynolds, author of Rip it Up and Start Again: Postpunk, 1978-84

-

"This is what happens when a really smart person takes on a really interesting topic. Japanese culture and fashion come shining into view."Grant McCracken, anthropologist and author of Culturematic and Chief Cultural Officer

-

"W. David Marx's Ametora answers the questions I had about the history and direction of menswear in Japan, and his research and analysis will undoubtedly be the authoritative word on the subject for years to come. This is a marvelously written, important, and necessary read for any student of global fashion today."Bruce Boyer, author of True Style

-

"W. David Marx's Ametora is a careful, complex, wildly entertaining cultural history of the highest caliber. This book will obviously be of immediate and considerable appeal to Japanophiles, classic-haberdashery connoisseurs, and other assorted fops, but its true and enormous audience ought to be anyone interested in the great hidden mechanisms of international exchange. In an age overrun with hasty jeremiads about the proliferation of global monoculture, Marx has given us quite a lot to reconsider. Ametora is a real pleasure."Gideon Lewis-Kraus, author of A Sense of Direction