By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

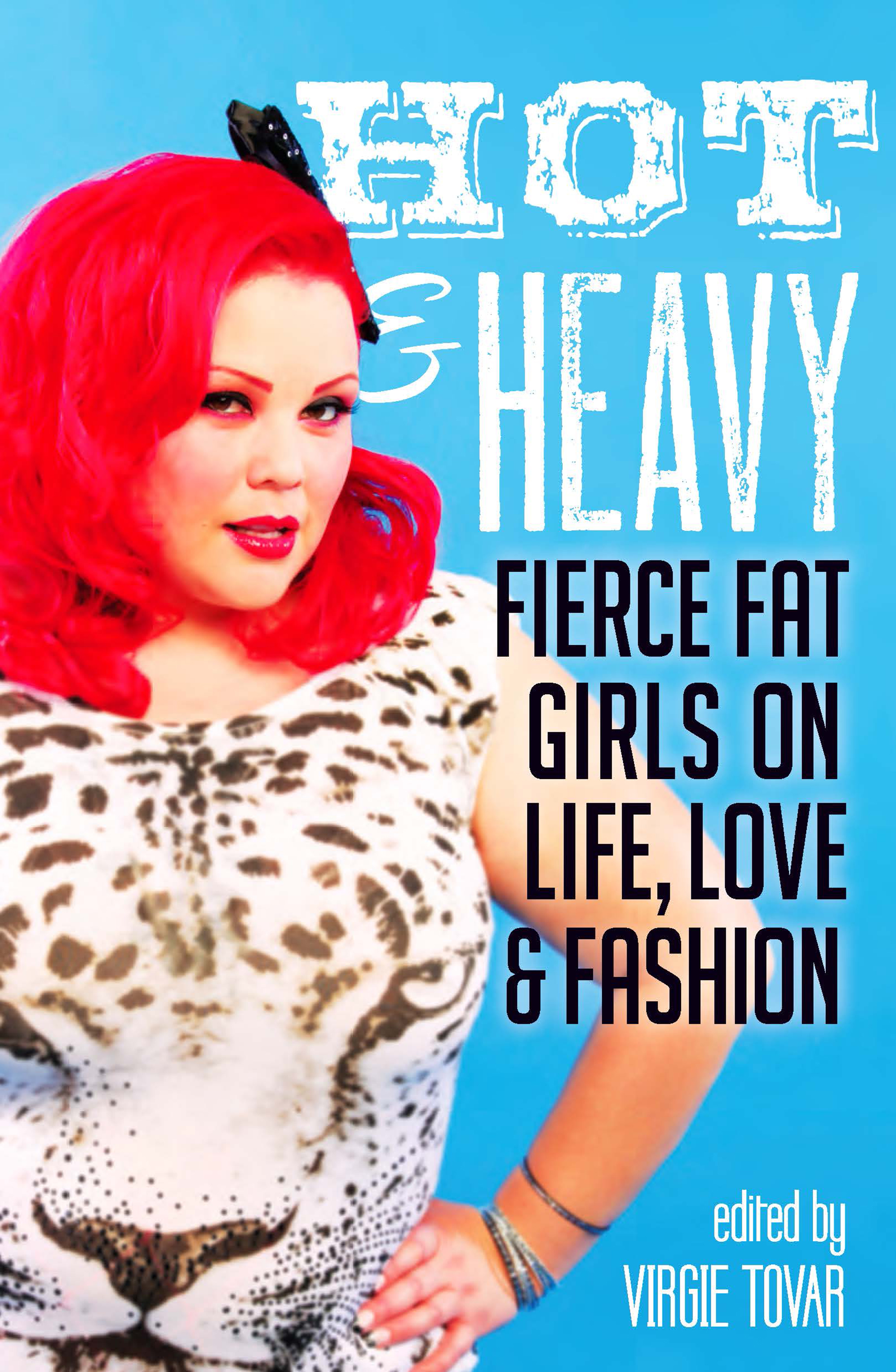

Hot & Heavy

Fierce Fat Girls on Life, Love & Fashion

Contributors

Edited by Virgie Tovar

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 30, 2012

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580054690

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 30, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this fun, fresh, fat-positive anthology, fat activist and sex educator Virgie Tovar brings together voices from an often-marginalized community to talk about and celebrate their lives. Hot & Heavy rejects the idea that being thin is best, instead embracing the many fabulous aspects of being fat—building fat-positive spaces, putting together fat-friendly wardrobes, turning society’s rules into personal politics, and creating supportive, inclusive communities.

Writers, activists, performers, and poets—including April Flores, Alysia Angel, Charlotte Cooper, Jessica Judd, Emily Anderson, Genne Murphy, and Tigress Osborn—cover everything from fat go-go dancing to queer dating to urban gardening in their essays, exploring their experiences with the word "fat,” pinpointing particular moments that have impacted the way they think and feel about their bodies, and telling the story of how they each became fat revolutionaries.

Groundbreaking and long overdue, Hot & Heavy is a fierce, sassy, thoughtful, authentic, and joyous collection of stories about unapologetically—and unconditionally—loving the body you’re in.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use