By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

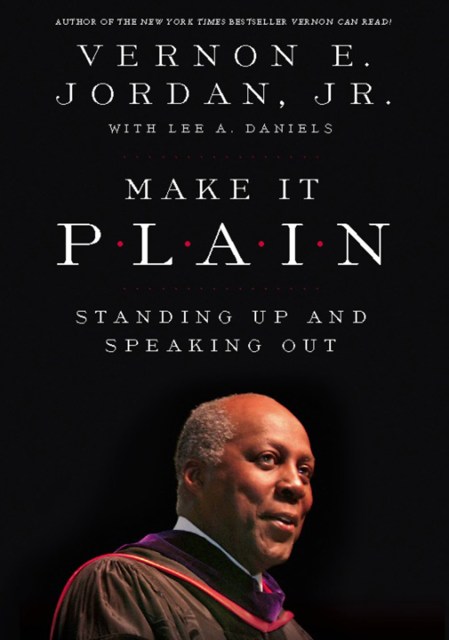

Make it Plain

Standing Up and Speaking Out

Contributors

With Lee A. Daniels

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 13, 2009

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786726363

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 13, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., one of the nation’s finest speakers, imbibed this tradition as a young man and has given it his own unique inflection from his work on the civil rights front lines, to the National Urban League, to positions of influence at the highest level of business and politics. A friend and confidant to presidents, Jordan has never forgotten the men and women — from Ruby Hurley to Wiley Branton to Gardner C. Taylor to Martin Luther King, Jr. — whose oratorical skill in service to social justice deeply influenced him. Their examples and voices, reflected in Vernon’s own, make this book both a history and an embodiment of black speech at its finest: Full of emotion, controlled force, righteous indignation, love of country, and awe in front of the God-given challenges ahead.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use