By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

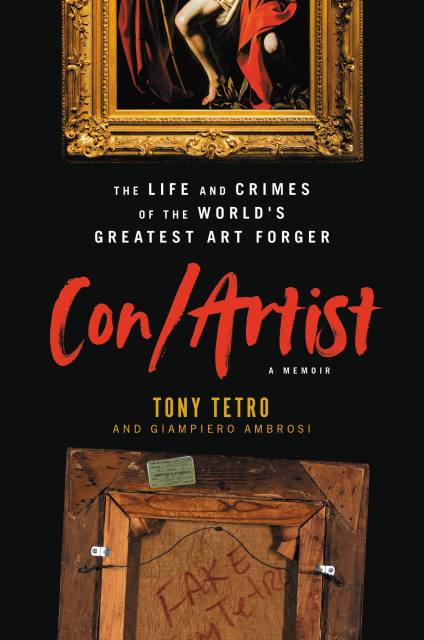

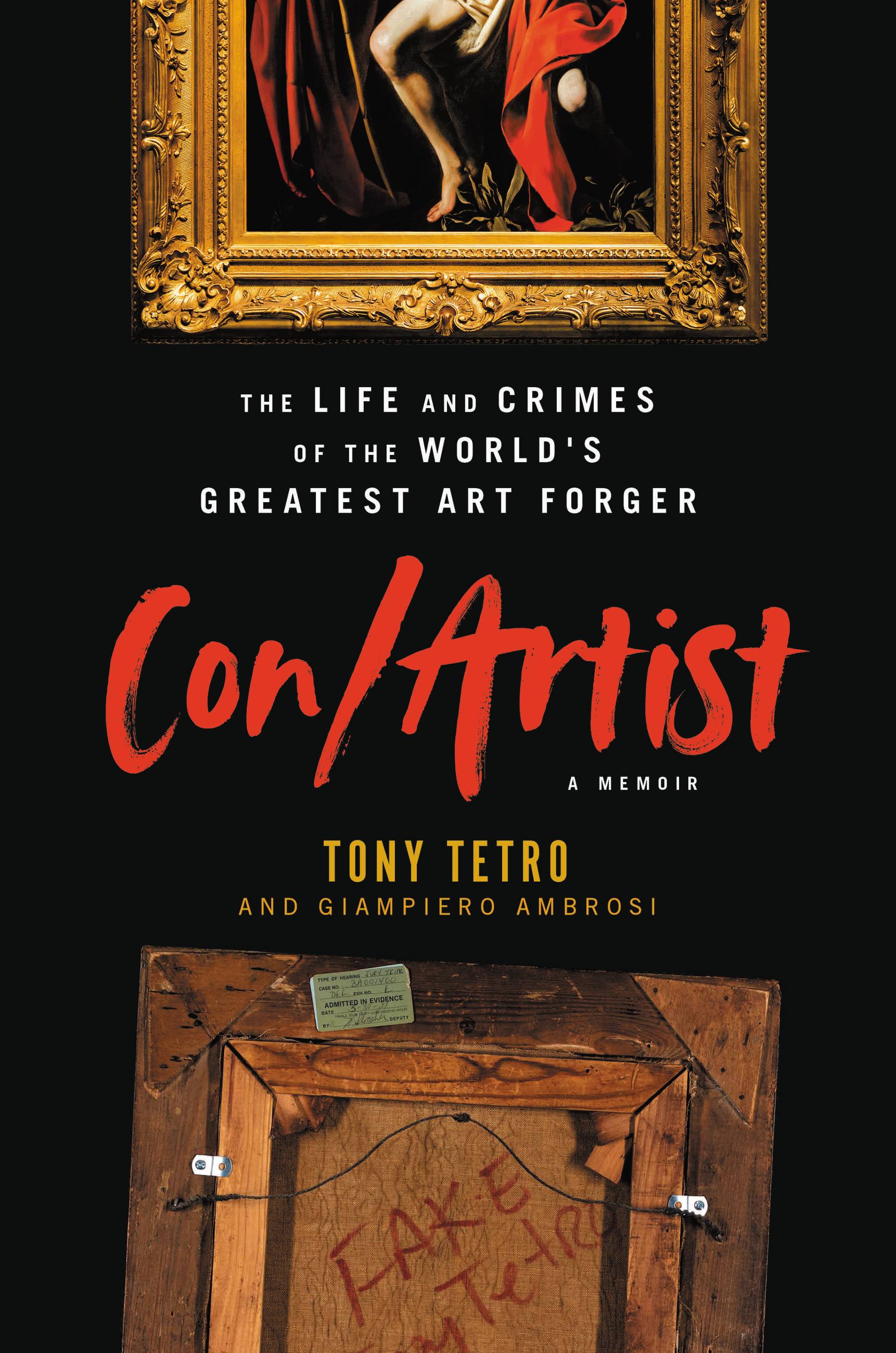

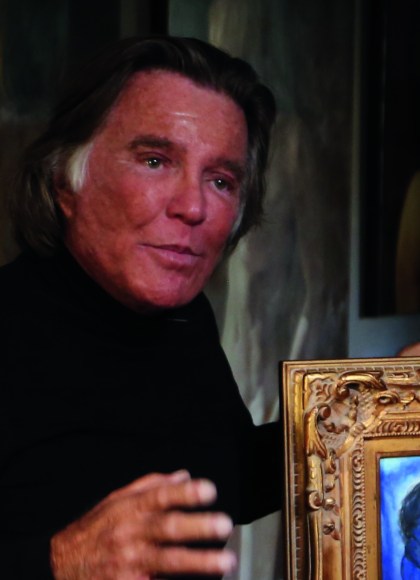

Con/Artist

The Life and Crimes of the World's Greatest Art Forger

Contributors

By Tony Tetro

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 22, 2022

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306826504

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 22, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The art world is a much dirtier, nastier business than you might expect. Tony Tetro, one of the most renowned art forgers in history, will make you question every masterpiece you’ve ever seen in a museum, gallery, or private collection. Tetro’s “Rembrandts,” “Caravaggios,” “Miros,” and hundreds of other works now hang on walls around the globe. In 2019, it was revealed that Prince Charles received into his collection a Picasso, Dali, Monet, and Chagall, insuring them for over 200 million pounds, only to later discover that they’re actually “Tetros.” And the kicker? In Tony’s words: “Even if some tycoon finds out his Rembrandt is a fake, what’s he going to do, turn it in? Now his Rembrandt just became motel art. Better to keep quiet and pass it on to the next guy. It’s the way things work for guys like me.” The Prince Charles scandal is the subject of a forthcoming feature documentary with Academy Award nominee Kief Davidson and coauthor Giampiero Ambrosi, in cooperation with Tetro.

Throughout Tetro’s career, his inimitable talent has been coupled with a reckless penchant for drugs, fast cars, and sleeping with other con artists. He was busted in 1989 and spent four years in court and one in prison. His voice—rough, wry, deeply authentic—is nothing like the high society he swanned around in, driving his Lamborghini or Ferrari, hobnobbing with aristocrats by day, and diving into debauchery when the lights went out. He’s a former furniture store clerk who can walk around in Caravaggio’s shoes, become Picasso or Monet, with an encyclopedic understanding of their paint, their canvases, their vision. For years, he hid it all in an unassuming California townhouse with a secret art room behind a full-length mirror. (Press #* on his phone and the mirror pops open.) Pairing up with coauthor Ambrosi, one of the investigative journalists who uncovered the 2019 scandal, Tetro unveils the art world in an epic, alluring, at times unbelievable, but all-true narrative.

-

"If you are an art lover, don’t miss this book. It will open your eyes to a world you might not have realized existed. And you may have to check your own collection to be sure you haven’t a Tetro on the wall."Lord Jeffrey Archer, #1 New York Times bestselling author

-

“Written with wit and disarming frankness….Mr. Tetro is a charming crook-scoundrel, a self-educated Runyonesque character who makes a fortune before he finally gets caught….Con/Artist reads like a step-by-step handbook for forgers, delivering a wealth of tips….One thing that comes across in Mr. Tetro’s story is his genuine...passion for art, especially the Renaissance masters.”The Wall Street Journal

-

“Think Goodfellas meets the art gallery….Tetro, with his laid-back attitude, wry take on the art world and streetwise humor, is not one for modesty….It’s hard not to be charmed by the tale of this average nobody who scams his way to the big time, only to blow all his money on like a mobster on fast cars, fast women, hard drinking, and hard drugs….Tetro emerges as a loveable rapscallion—part highly skilled conjurer, part practical joker—who points out what the sceptics have always tended to suspect: that the art market emperors are strutting their stuff in no clothes….Tetro’s frankness is invigorating….His art appreciation, however rough and ready…can feel delightfully fresh.”Times of London

-

“Beneath the grit and the glamor is a fascinating tale of a diligent, self-taught artist with a good work ethic and a great natural talent… A magician never reveals his secrets, but Tetro is no magician. Readers hankering for the nitty gritty of how he made his fakes won’t be disappointed....From start to finish Tetro’s passion for art and his knack for drama carry the reader through.”Spectator

-

“Remarkable…electric memoir.”AirMail

-

**Winner of the AudioFile Earphones Award**AudioFile (audiobook)

“[Narrator] Richard Ferrone captures the casual confidence, wobbly moral compass, and street-smart charm of Tony Tetro, an art forger extraordinaire.…This audiobook will lead listeners to question everything they thought they knew about the value of fine art.” -

“Tetro, one of the most prolific art forgers of the 20th century, paints his own life story with flair in this cinematic memoir… Written in a colorful, conversational voice and blending memoir, art history, and true crime, Tetro’s account takes readers on a turbulent, fast-paced, high-stakes roller-coaster ride. This is the art world’s The Wolf of Wall Street.”Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

“[Tetro’s] memoir, cowritten with investigative journalist Giampiero Ambrosi, is absolutely fascinating, full of the kind of evocative writing and precise detail that brings an autobiography to life. He might have been doing something illegal, but it’s awfully hard not to like Tony Tetro. Like reformed con artist Frank W. Abagnale (Catch Me If You Can), he seems straightforward, open about his crimes, and just a bit proud of his success as a crook. A welcome addition to any true-crime shelf.”Booklist (starred review)

-

"Compulsively readable."Daily Mail

-

“A successful, prolific art forger tells his remarkable story…He has amusing things to say about people who have too much money and not enough sense…. Tetro tells his rollicking story well, and the result is a unique narrative. An entertaining account that shines a light onto a shady world as well as a personal story of hubris and redemption.”Kirkus Reviews

-

"First, a warning: after reading this book, you might find yourself inspecting the pictures hanging in museums and galleries a little more closely....This mind-boggling and absorbing memoir charts the rise and fall of the American forger, who made headlines when some of his Monets were discovered in the collection of King Charles III. Expect art history, big money, sex, and corruption."Monocle

-

“Juicy….[Tetro] promises ‘an art history lesson wrapped in sex, drugs, and Caravaggio.’ AKA all the things we look for in a great holiday party.”Urban Daddy

-

“If you love a story of wild excess, here you go. How much will you take Tony Tetro’s word as truth? Read and decide for yourself.”BookRiot

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use