By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

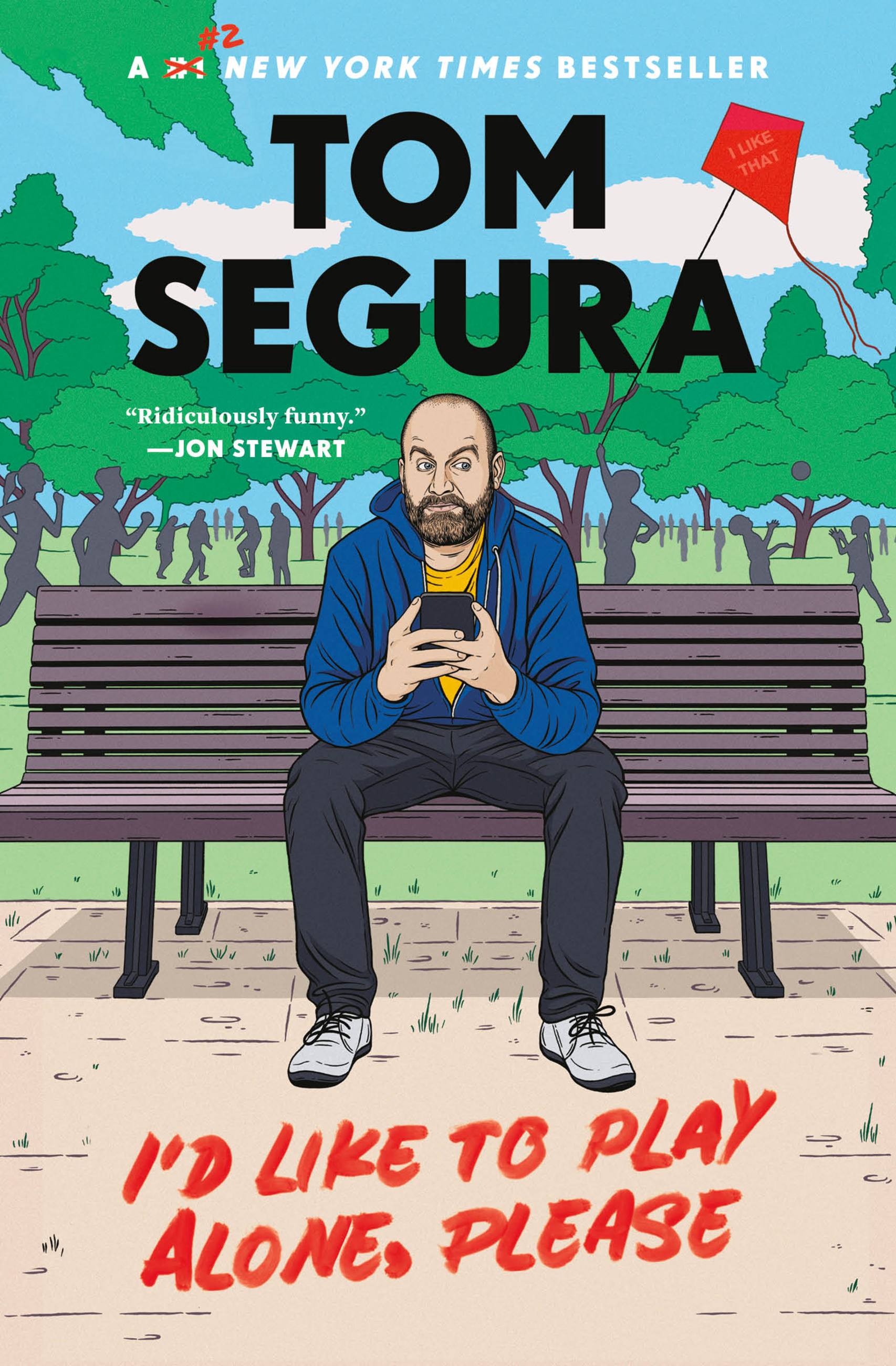

I’d Like to Play Alone, Please

Essays

Contributors

By Tom Segura

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 14, 2022

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538704622

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 14, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From a massively successful stand-up comedian and co-host of chart-topping podcasts “2 Bears 1 Cave” and “Your Mom’s House,” hilarious real-life stories of parenting, celebrity encounters, youthful mistakes, misanthropy, and so much more.

Tom Segura is known for his twisted takes and irreverent comedic voice. But after a few years of crazy tours and churning out podcasts weekly, all while parenting two young children, he desperately needs a second to himself. It’s not that he hates his friends and family — he’s not a monster — he’s just beat, which is why his son’s (ruthless) first full sentence, “I’d like to play alone, please,” has since become his mantra.

In this collection of stories, Tom combines his signature curmudgeonly humor with a revealing look at some of the ridiculous situations that shaped him and the ludicrous characters who always seem to seek him out. The stories feature hilarious anecdotes about Tom's time on the road, including some surreal encounters with celebrities at airports; his unfiltered South American family; the trials and tribulations of parenting young children with bizarrely morbid interests; and, perhaps most memorably, experiences with his dad who, like any good Baby Boomer father, loves to talk about his bowel movements and share graphic Vietnam stories at inappropriate moments. All of this is enough to make anyone want some peace and quiet.

I’D LIKE TO PLAY ALONE, PLEASE will have readers laughing out loud and nodding in agreement with Segura's message: in a world where everyone is increasingly insane, sometimes you just need to be alone.

-

“I’d Like to Play Alone, Please is a stereotypically masculine tour de force with farts, football and a third thing starting with “f” that’s not fit to print, occasionally interrupted by completely disarming, heartfelt sentiments. Then followed by more poop jokes…The book is funny, surprising and even sweet at times."Associated Press

-

"Segura’s quick wit and irreverent charm come across loud and clear in “I’d Like to Play Alone, Please,” a collection of essays that reads like a stand-up set deserving of a standing ovation."The Los Angeles Times

-

"[L]augh out loud funny. . .Segura is impish and charming and clever and self-deprecating."Forbes

-

"Stand-up comedian Tom Segura built his career making laugh-out-loud funny observations live, onstage and for his multiple podcasts. With the fittingly titled I’d Like To Play Alone, Please—so named for Segura’s son’s brutally pointed first sentence—the witty, relatable, exhausted curmudgeon welcomes audiences into an equally entertaining but more intimate romp."AV Club

-

“Tom Segura delivers a treatise that is as timely as it is thought provoking and…actually, he did something better…a book that’s ridiculously funny!!!! If you want to live inside the mind of one of the best comics out there, here’s your chance. I hear the audio version is for shit, though…”Jon Stewart

-

“One of the funniest men I know has written an extremely funny book of stories that he's never told on stage. There's lots to learn too, like how close Tom came to playing in the NFL (not very); or why sitting next to Mike Tyson on a plane is the most dangerous and exciting thing in world; or how Tom continues to be one of the greatest storytellers on the planet."Ali Wong

-

“Tom Segura is a great guy, an amazing friend, and a limitless well of hilarious stories. He also has an appreciation for the absurdity of life that borders on mental illness. This book is a window into his beautifully f*cked-up mind, where some of the dumbest people and the ridiculous things they do take center stage, all masterfully animated by one of the best stand-up comics on earth. He’s my favorite kind of comic because his take on life is legitimately therapeutic. His enthusiasm for stupid sh*t is so contagious that it actually changes your mood and convinces you to join in on his way of seeing it. I love him to death, and his book is f*cking awesome.”Joe Rogan

-

"[An] rrreverent collection of personal stories. . .Segura’s candor is undeniably entertaining. Fans will find this a riot."Publishers Weekly

-

"While Segura’s off-color humor is not for everyone, his fans will doubtlessly enjoy both his essays and the included black-and-white photos. Often crude but undeniably funny."Kirkus Reviews

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use