By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

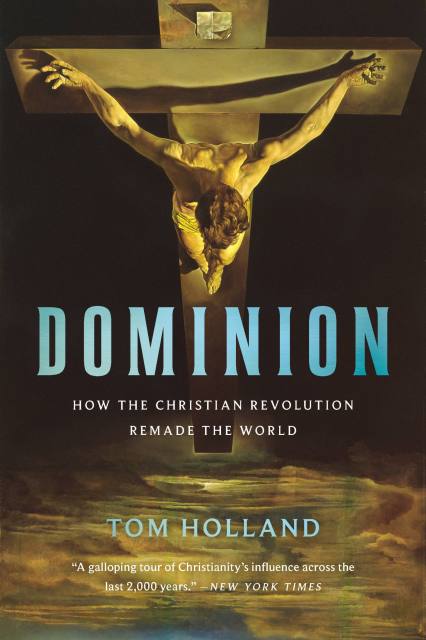

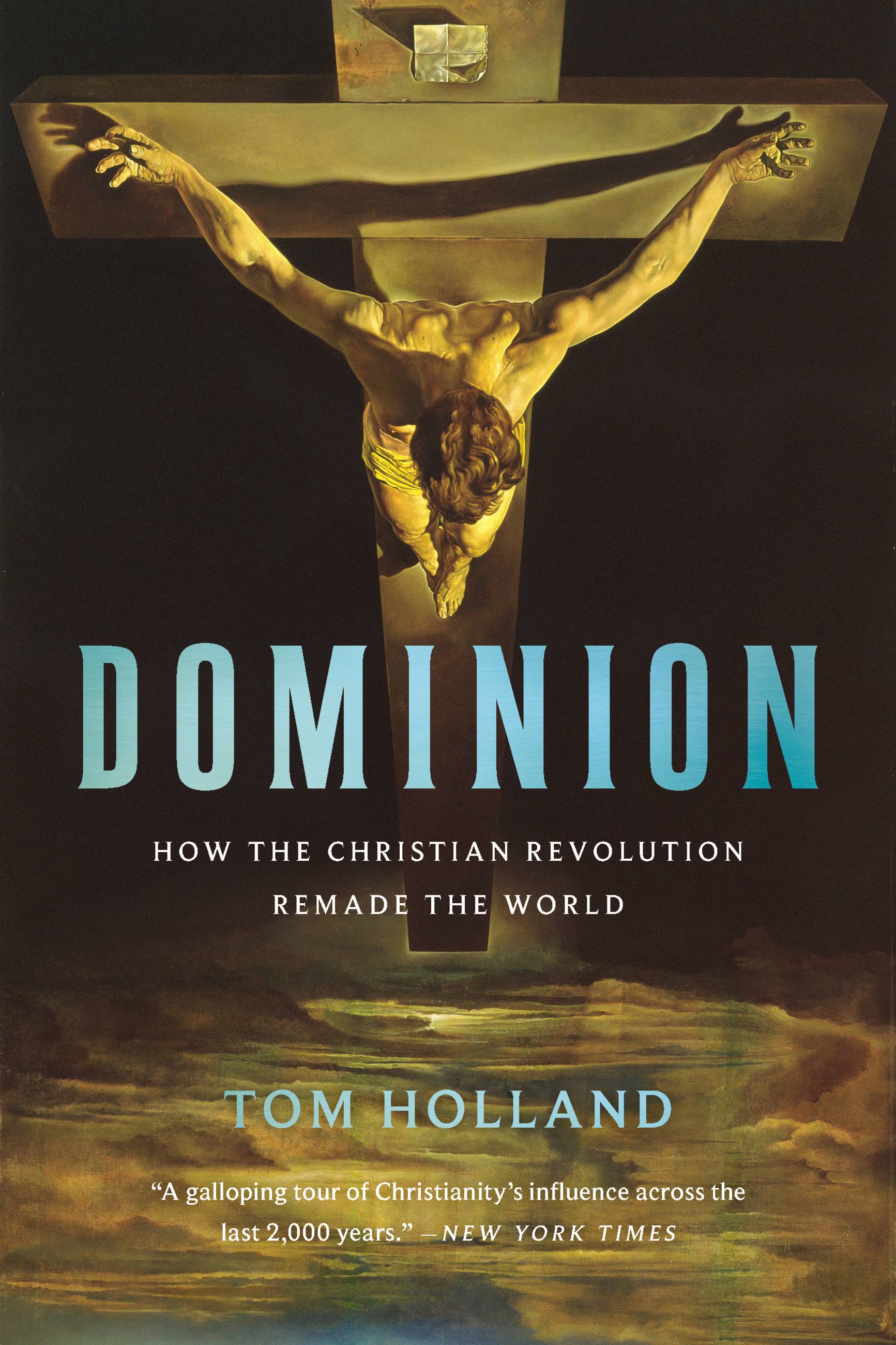

Dominion

How the Christian Revolution Remade the World

Contributors

By Tom Holland

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 29, 2019

- Page Count

- 624 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465093526

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Digital download $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $51.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $32.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 29, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“A galloping tour of Christianity’s influence across the last 2,000 years.” —New York Times

Crucifixion, the Romans believed, was the worst fate imaginable, a punishment reserved for slaves. How astonishing it was, then, that people should have come to believe that one particular victim of crucifixion—an obscure provincial by the name of Jesus—was to be worshipped as a god. Dominion explores the implications of this shocking conviction as they have reverberated throughout history. Today, the West remains utterly saturated by Christian assumptions. As Tom Holland demonstrates, our morals and ethics are not universal but are instead the fruits of a very distinctive civilization. Concepts such as secularism, liberalism, science, and homosexuality are deeply rooted in a Christian seedbed. From Babylon to the Beatles, Saint Michael to #MeToo, Dominion tells the story of how Christianity transformed the modern world.

Genre:

-

“This lively, capacious history of Christianity emphasizes the extent to which the religion still underpins Western liberal values.”New Yorker

-

“A galloping tour of Christianity's influence across the last 2,000 years, with vivid vignettes scattered across the centuries, and a concluding argument the Christian faith, 'the most influential framework for making sense of human existence that has ever existed,' still shapes the way that even the most secular modern people think about the world.”Ross Douthat, New York Times

-

“A sweeping narrative.... [Holland] is an exceptionally good storyteller with a marvelous eye for detail... excellent fun.”Economist

-

“Holland is a spellbinding storyteller, here recounting how Christianity created the bedrock of Westerners' sense of what is ordinary today, whether one is observant or not.”John McWhorter, The Week

-

“In a year full of political non-fiction books, I have been most gripped by Tom Holland’s Dominion, his exciting history of the revolutionary impact of Christianity on the West.”New Statesman

-

“An absorbing survey of Christianity's subversive origins and enduring influence is filled with vivid portraits, gruesome deaths and moral debates...Holland has all the talents of an accomplished novelist: a gift for narrative, a lively sense of drama and a fine ear for the rhythm of a sentence.”Guardian (UK)

-

“An engaging book.”Times (UK)

-

“An exhaustive, demanding and hugely impressive interpretation of our past, bursting with fresh ideas and perspectives on every page.”Sunday Times

-

“An ambitious account of the history and enduring influence of Christianity. Holland argues that the modern world has been shaped by the consequences of the life and death of Jesus.”Daily Mail (The Year’s Most Essential Books)

-

“What in other hands could have been a dry pedantic account of Christianity's birth and evolution becomes in Holland's an all-absorbing story.... It takes a master storyteller to translate the development of a philosophical notion into a captivating story, and Holland proves to be one.... Holland offers a remarkably nuanced and balanced account of two millennia of Christian history -- intellectual, cultural, artistic, social and political. The book's scope is breathtaking.”Literary Review

-

“A masterpiece of scholarship and storytelling, Dominion surpasses Holland's earlier books in its sweeping ambition and gripping presentation.... Dominion presents a rich and compelling history of Christendom.”New Statesman

-

“This is popular history and readable. It has passages of striking writing and...lots of substance. It's imagery and points of modern comparison often have the vividness that makes excellent broadcast documentary. So there is a good read here.”Church Times

-

“Readers of Dominion will find themselves better informed, but they will also be repeatedly disturbed and provoked and driven to rethink just how they understand the relationship between religion and the development of culture. I mean that as high praise.”Christianity Today

-

“Tom Holland has a grand thesis. He explores it with energy, advances it with panache, and pulls it off with a flourish. His lively and absorbing project is at once a serviceable church history, a studied engagement with Christianity's finest and darkest hours, and a compelling argument.... Above all, Holland portrays a legacy and a history boundlessly enjoyable and consistently provocative.”Christian Century

-

“[B]ig and richly satisfying new history of Christianity, ...Dominion is superior even to Holland's much-loved earlier book Rubicon and every bit as crowded with vividly-drawn personalities.”Open Letters Monthly

-

“With characteristic expertise and panache, Tom Holland shows in Dominion that the most distinctive fruits of Christian piety in the West have been unparalleled industry, liberation, and charity.”Claremont Review of Books

-

“Historian Tom Holland's new blockbuster, Dominion makes clear that what we're undoing, in our current moment of cultural crisis, is Christianity.”Angelus

-

“Tom Holland, has done a great service to current discussions on the relationship between Christianity and Western civilization.”Providence Magazine

-

“The history of Christian influence could not be better served than with Tom Holland's Dominion.... Holland's exploration of Christianity's notion of inherent worth in all humans is deftly handled, and at times it rises to something akin to greatness....This latest work elevates him to the front of the top ranks of our scholarly, yet popular, historians.”LA Daily Journal

-

“An engaging work...Holland exhibits a wide and deep historical knowledge...even readers who might not agree with Holland's thesis will enjoy his take on key periods of Western history.”Library Journal (starred)

-

“Christianity may not be on the march, but its principles continue to dominate in much of the world; this thoughtful, astute account describes how and why... Holland delivers penetrating, often jolting discussions on great controversies of Western civilization in which war, politics, and culture have formed a background to changes in values... An insightful argument that Christian ethics, even when ignored, are the norm worldwide.”Kirkus Reviews (starred)

-

“Terrific: bold, ambitious and passionate.”Peter Frankopan, author of The Silk Roads

-

“Tom Holland is fun to read, monstrously erudite, wickedly joyful, and ahead of the established consensus, on average, by 4 years, three months, and 2 days.”Nassim Nicholas Taleb, author of The Black Swan

-

“This extraordinary book is vintage Tom Holland: history boldly and elegantly retold, with fascinating interconnections traced to create a narrative that cannot fail to stimulate, for it leads to a never-ending question.”Diarmaid MacCulloch, author of The Reformation

-

“At a moment when popular debates over 'faith' and 'reason' have become fashionable, Tom Holland brilliantly reminds us that the most essential values claimed by all sides arise from a long and complex cultural history of Christian moral imagination -- one we would do well to remember.”David Bentley Hart, author of The Experience of God