By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

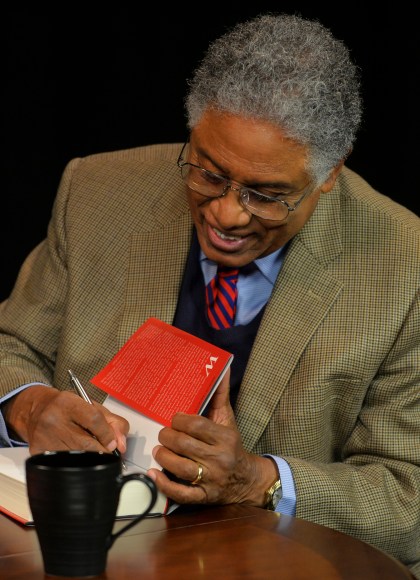

The Vision of the Anointed

Self-Congratulation as a Basis for Social Policy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 28, 1996

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465089956

Price

$19.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 28, 1996. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

One of America’s pre-eminent economists offers a provocative critique of the failures of liberalism

In The Vision of the Anointed, Thomas Sowell presents a devastating critique of the mind-set behind the failed social policies of the past thirty years. Sowell sees what has happened during that time not as a series of isolated mistakes but as a logical consequence of a tainted vision whose defects have led to crises in education, crime, and family dynamics, and to other social pathologies. In this book, he describes how elites—the anointed—have replaced facts and rational thinking with rhetorical assertions, thereby altering the course of our social policy.

In The Vision of the Anointed, Thomas Sowell presents a devastating critique of the mind-set behind the failed social policies of the past thirty years. Sowell sees what has happened during that time not as a series of isolated mistakes but as a logical consequence of a tainted vision whose defects have led to crises in education, crime, and family dynamics, and to other social pathologies. In this book, he describes how elites—the anointed—have replaced facts and rational thinking with rhetorical assertions, thereby altering the course of our social policy.

-

"This is as compelling an explanation as any for the seemingly disproportionate amount of condescension and politically correct invective that emanates from the liberal side of the political spectrum toward the conservative opposition."Scott McConnell, Wall Street Journal

-

"As always, Sowell's analysis is well informed and displays a great deal of that increasingly uncommon quality, common sense... In the largest sense, The Vision of the Anointed is a book about the perils of ideology—those dazzling intellectual-moral constructions that seduce the unwary into ignoring the way the world works for the sake of dreams about the way it must."Roger Kimball, The American Spectator

-

"Mr. Sowell's eye is sharp, and everyone who has been up against progressive orthodoxy will find his or her own candidate for Most Annoying Liberal Kiss-Off Award."Suzanne Garment, Washington Times

-

"Avid conservatives, for whom Sowell is a true-blue intellectual force, will certainly seize upon his analysis for succor."Booklist

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use