By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

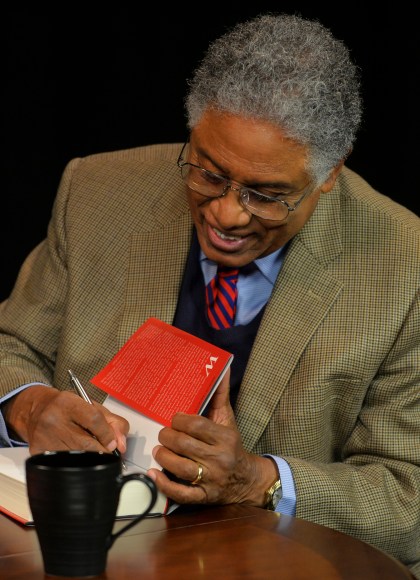

Intellectuals and Society

Revised and Expanded Edition

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 6, 2012

- Page Count

- 680 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465025220

Price

$26.99Price

$33.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $26.99 $33.99 CAD

- ebook (Revised) $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 6, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Intellectuals and Society not only examines the track record of intellectuals in the things they have advocated but also analyzes the incentives and constraints under which their views and visions have emerged. One of the most surprising aspects of this study is how often intellectuals have been proved not only wrong, but grossly and disastrously wrong in their prescriptions for the ills of society — and how little their views have changed in response to empirical evidence of the disasters entailed by those views.

-

"Thomas Sowell is, in my opinion, the most interesting philosopher at work in America."Paul Johnson, author of Modern Times

-

"It's a scandal that economist Thomas Sowell has not been awarded the Nobel Prize. No one alive has turned out so many insightful, richly researched books."Steve Forbes

-

“Certainly passionate about the subject, Sowell is perceptive and at times brilliant….another well-written work….[A]n entertaining read.”Choice

-

“Intellectuals and Society unravels in clear, non-intellectual terms some of the puzzling phenomena in the world of the intellectuals—analyzing the nature and role of intellectuals in society and exploring the ominous implications of that role for the direction in which the Leftist intelligentsia are taking our society and Western civilization in general.”Conservative Book Club

-

“Sowell looks at war with a steady gaze, never supposing that peaceful economic competition will entirely replace it. He makes good sport of deflating the unthinking rhetorical antics of many pacifist intellectuals…He [Sowell] very well knows the most important thing about his life’s work: in the end he is an economist who points beyond the often-dismal science to an economy of the spirit.”Society (Springer)

-

“One comes away from reading Sowell with a sense of having encountered the kind of analytic incisiveness and depth that was practiced by the best thinkers of the Enlightenment, men like Adam Smith, or the triune authors of the Federalist Papers, who both read the human heart and knew the human story…Sowell is a fiercely polemical writer, yet one whose clear, straightforward prose illumines everything it touches. He’s as honest and valuable an intellectual as America will ever produce. If the force of an example is needed to improve the breed, he’s it.”Academic Questions (Springer)

-

“Sowell is at his best, which is very good indeed, when he deals with the free market. He points out a fallacy in the complaints of many critics of the market who stress the unequal distribution of wealth and income in contemporary America…Sowell’s skillful use of evidence emerges again when he confronts another popular charge against the free market…an excellent book as a whole.”The Independent Review

-

“The illustrations of his [Sowell’s] argument are quite compelling…the chapter on intellectuals and the economy is, naturally, among the most illuminating…”The American Spectator

-

“Intellectuals and Society is something of a summa of Sowell’s concerns over the last 40 years… The power of Sowell’s book owes to its concreteness. He has an enviable gift for showing that many of our social problems arise from the differences between ‘the theories of intellectuals and the realities of the world.’… this learned and thoughtful book demonstrates what its author has in mind when he calls for a humane reintegration of intellect, wisdom, and respect for the stubborn realities that constitute our world.”City Journal

-

"It (Intellectuals and Society) is chock full of interesting ideas – like much of Sowell’s work."Regulation, CATO Institute

-

“Sowell takes aim at the class of people who influence our public debate, institutions, and policy. Few of Sowell’s targets are left standing at the end, and those who are stagger back to their corner, bloody and bruised.”National Review Online

-

“Mr. Sowell builds a devastating case against the leftist antiwar political and intellectual establishment”Washington Times

-

"America's best writer on economics, particularly when that discipline intersects with politics."World

Newsletter Signup

By clicking 'Sign Up,' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group's Privacy Policy and Terms of Use