By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

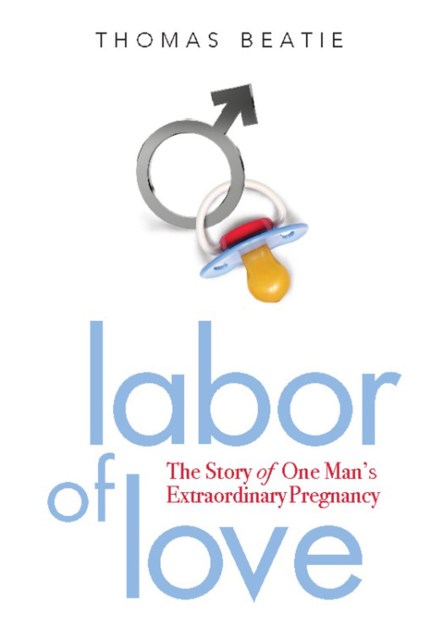

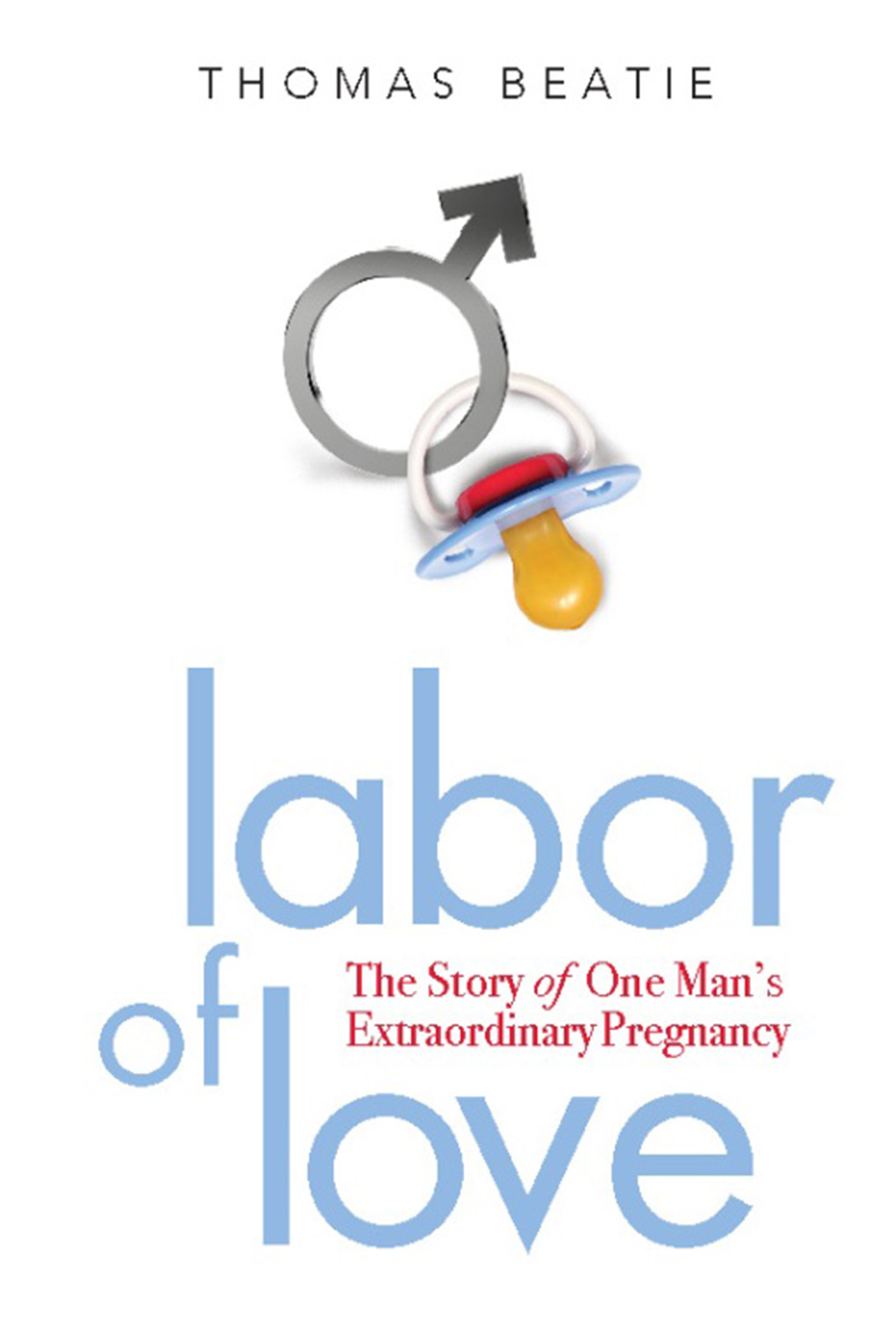

Labor of Love

The Story of One Man's Extraordinary Pregnancy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 4, 2008

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786741106

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 4, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Thomas Beatie electrified the world in April 2008 with his announcement that he was seven months pregnant and due to give birth in July. The news made headlines across the globe, but it’s only one chapter in a fascinating saga. Labor of Love reveals Beatie’s unique life experiences: his less-than-idyllic childhood in Hawaii, his feelings of being a young man trapped in the body of a woman, his fight to conceive a child, and the obstacles surrounding the delivery. This astonishing narrative permits an intimate look at a family that refuses to let other people’s definitions of family deter them from creating one on their own terms. Labor of Love is much more than the story of a unique pregnancy and birth — it’s a beautiful and controversial love story about going against the tide, a powerful statement about the evolution of family and identity in the new millennium.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use