By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

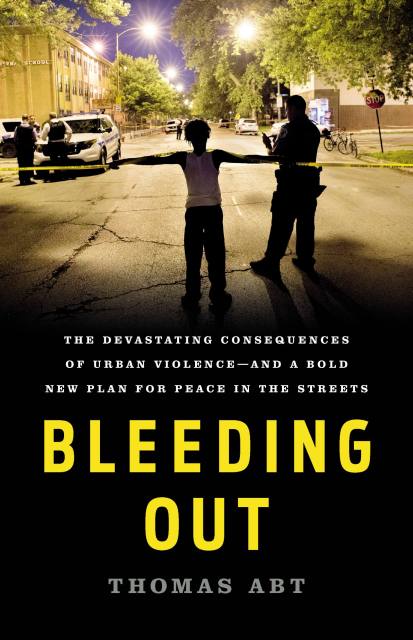

Bleeding Out

The Devastating Consequences of Urban Violence—and a Bold New Plan for Peace in the Streets

Contributors

By Thomas Abt

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 25, 2019

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541645714

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 25, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From a Harvard scholar and former Obama official, a powerful proposal for curtailing violent crime in America

Urban violence is one of the most divisive and allegedly intractable issues of our time. But as Harvard scholar Thomas Abt shows in Bleeding Out, we actually possess all the tools necessary to stem violence in our cities.

Coupling the latest social science with firsthand experience as a crime-fighter, Abt proposes a relentless focus on violence itself — not drugs, gangs, or guns. Because violence is “sticky,” clustering among small groups of people and places, it can be predicted and prevented using a series of smart-on-crime strategies that do not require new laws or big budgets. Bringing these strategies together, Abt offers a concrete, cost-effective plan to reduce homicides by over 50 percent in eight years, saving more than 12,000 lives nationally. Violence acts as a linchpin for urban poverty, so curbing such crime can unlock the untapped potential of our cities’ most disadvantaged communities and help us to bridge the nation’s larger economic and social divides.

Urgent yet hopeful, Bleeding Out offers practical solutions to the national emergency of urban violence — and challenges readers to demand action.

Coupling the latest social science with firsthand experience as a crime-fighter, Abt proposes a relentless focus on violence itself — not drugs, gangs, or guns. Because violence is “sticky,” clustering among small groups of people and places, it can be predicted and prevented using a series of smart-on-crime strategies that do not require new laws or big budgets. Bringing these strategies together, Abt offers a concrete, cost-effective plan to reduce homicides by over 50 percent in eight years, saving more than 12,000 lives nationally. Violence acts as a linchpin for urban poverty, so curbing such crime can unlock the untapped potential of our cities’ most disadvantaged communities and help us to bridge the nation’s larger economic and social divides.

Urgent yet hopeful, Bleeding Out offers practical solutions to the national emergency of urban violence — and challenges readers to demand action.

Genre:

-

"A fine new book, Bleeding Out,by Thomas Abt, sheds light on the issue of urban violence and offers some practical, street-tested solutions to it...Abt's approach is, in the classic American manner, an empirical one...[He] recommends neither noxious stop-and-frisk policies nor amorphous community policing but, instead, what he calls 'partnership-oriented crime prevention'-using all of a city's resources."Adam Gopnik, New Yorker

-

"Thomas Abt is a critical voice in our national discourse on crime and violence. His work bears the crucial intellectual virtues of exhaustive research, conscientious study, and meticulously drawn conclusions. Agree or disagree with him but by all means read him."Jelani Cobb, Ira A. Lipman Professor of Journalism, Columbia Journalism School

-

"[Abt's] thinking breaks from political orthodoxy on both the left and the right: The main reason violence is so persistent in the United States, he believes, isn't that gun laws are too weak (a common argument among liberals) or that police critics have hamstrung tough street-clearing tactics (an often-stated conservative belief). It's that not enough cities, whatever their political leanings, are properly using basic strategies that are known to persuade would-be shooters not to acquire guns, and not to use them on one another, in the first place."Atlantic

-

"[Abt] presents a vision for dealing with urban violence by fundamentally rethinking how law enforcement and other government resources are used...Bleeding Out makes a compelling case that there is a path forward."Vox

-

"Bleeding Out fills an important gap in the emerging criminal justice canon...For Abt, reducing the homicide rate is the first step toward achieving broader social change...Bleeding Out makes a strong case that 'sustainable crime control does not happen without social justice, and vice versa.'"New York Law Journal

-

"Abt's book leans into impact evaluations, interviews, and systematic reviews to build a framework for violence reduction that is at once non-ideological and internally coherent...A thoughtful, research-driven examination of some of the thorniest, most painful issues."The Crime Report

-

"Focus on the violence itself, separately from our endless political bickering...The immediate actions Abt counsels are not all that expensive, and they are not all that partisan...They deserve strong support."National Review

-

"Abt skillfully mixes academic research, information about previously instituted pilot programs, and interviews with families devastated by gun-related homicides to propose a multistep solution that he believes will reduce gun deaths in cities across the country...A useful addition to the necessarily growing literature on urban violence."Kirkus

-

"Abt persuasively argues that as much as poverty causes violence, violence also causes poverty-alleviating the former, therefore, would not only save thousands of needlessly lost lives, but help reinvigorate some of America's most benighted communities."Washington Free Beacon

-

"Contrary to conventional wisdom and popular culture, violence is not a permanent feature of urban life but a solvable problem, if you leave your ideology at the door and look at data on what works. Thomas Abt is one of the world's authorities on urban crime, and this fascinating and important book offers many surprises, much insight, and positive recommendations."Steven Pinker, Johnstone Professor of Psychology, Harvard University, and author of The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence has Declined

-

"Bleeding Out is a readable guide for newcomers and a corrective for academics, establishing that urban violence truly is our greatest criminal justice problem. Thomas Abt knows what matters: neither the get-tough rhetoric from the right nor the denial on the left really address what ails urban poor people as they struggle with violent crime."Jill Leovy, author ofGhettoside: A True Story of Murder in America

-

"Bleeding Out is an illuminating and engaging book. Building on evidence involving anti-violence evaluations and dozens of face-to-face interviews, Thomas Abt's new paradigm for understanding and combatting urban violence is persuasive. This is required reading for all concerned citizens and policymakers."William Julius Wilson, Lewis P. and Linda L. Geyser University Professor, Harvard University

-

"From dangerous street corners to the corner offices of power, Thomas Abt focuses like a laser on the critical issues of crime and public safety. Policy makers, law enforcers, and community leaders should read his work if they're serious about making America safe-for all of us!"Michael A. Nutter, mayor of Philadelphia, 2008-2016