Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

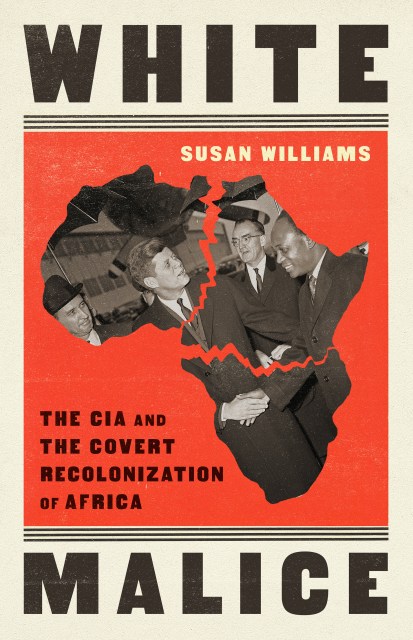

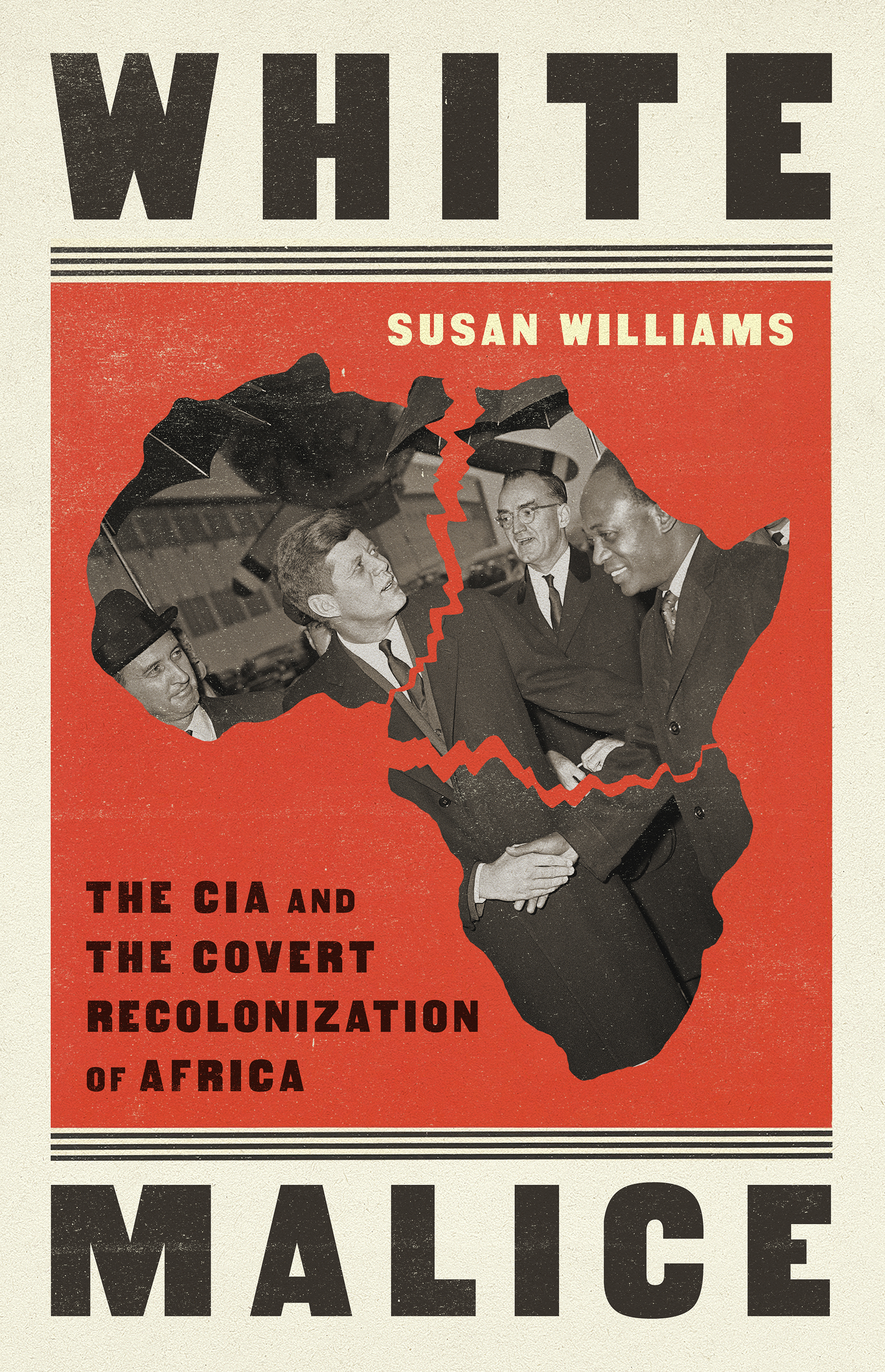

White Malice

The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 10, 2021

- Page Count

- 688 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541768284

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $44.99

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $32.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 10, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In 1958 in Accra, Ghana, the Hands Off Africa conference brought together the leading figures of African independence in a public show of political strength and purpose. The charismatic Kwame Nkrumah, who had just won Ghana’s independence, led a determined appeal for Pan-Africanism. Young, idealistic leaders across the continent, as well as African Americans seeking civil rights at home, heeded his call. Yet, a moment that signified a new era of African freedom simultaneously marked a new era of foreign intervention and control.

In White Malice, Susan Williams unearths the CIA’s covert operations from Ghana to the Congo to the UN, which frustrated the attempts of Africa’s new generation of nationalist leaders to establish democratic governance. These revelations dramatically upend the conventional wisdom that African nations failed to establish effective, democratic states on their own accord. As the old European powers moved out, the US moved in.

Drawing on original research and recently declassified documents, Williams introduces readers to idealistic African leaders and to the secret agents, ambassadors, and even presidents who deliberately worked against them, forever altering the future of a continent.

Genre:

-

“[White Malice] overflows with fascinating information, original research, and bold ideas.”NPR.org

-

“Williams does a nice line in intrigue. There is a John le Carré quality to many of the episodes [in White Malice]. CIA operatives turn up as journalists, interpreters, businessmen and private secretaries, sometimes bearing suitcases of cash. … [An] entertaining narrative.”Financial Times

-

“A revelatory, meticulous new book.”UnHerd

-

“White Malice is a triumph of archival research… In White Malice, the CIA’s capacity for committing murder and sowing discord is on full display.”Jacobin

-

“Her thesis threatens to disappear amid a forest of historical detail, but readers interested, especially, in Ghana and Congo will find her book absorbing.”Boston Globe

-

“Exposes the astonishing extent of the CIA’s activities across central and west Africa in the 1950s and early 60s.”The Observer

-

“White Malice is a triumph of archival research, and its best moments come when Williams allows the actors on both sides to speak for themselves.”Africa is a Country

-

“A new book from historian and academic Dr Susan Williams is always an eagerly awaited event – and White Malice: The CIA and the Neocolonialisation of Africa is no exception. Williams has woven together many of the themes of previous studies to present a searing indictment of how Western powers interfered with, plundered and sabotaged the interests of newly independent African nations and their leaders.”African Business

-

“[A] devastating, superbly researched account.”Daily Maverick

-

“This thoroughly-researched account of CIA interference in two newly independent African nations makes for sobering reading… sombre and sharp.”The Scotsman

-

“This is a book that every prospective leader in Africa must read."Africa Briefing

-

“This gripping book meticulously uncovers the role of covert western interference in two countries.”Labour Hub

-

“...[T]he author merits our heartfelt thanks for her indefatigable labor that has rescued a history that needs to be better known and will be instrumental in the final defeat of U.S. imperialism on the beleaguered continent.”CovertAction

-

“Williams takes great care to provide evidence of just how far the CIA’s reach went, the organizations it funded, the many different ways it tried to gain access and the willingness to use violence to achieve their goal of a compliant and capitalist Africa…This book is essential reading.”Spring Magazine

-

“Written in such an engrossing journalistic style that it sometimes reads like a spy thriller.”Peace Now

-

“[Susan Williams’] sensational book … [is] essential reading for anyone who wants to understand how low the West can go, and how imperialism has shaped African history.”Counterfire

-

“Wonderful, a landmark.”Lobster Magazine

-

“In White Malice, Williams tells an essential history that is usually repressed in public discourse rather than acknowledged, offering counterfactuals for what could have been and, importantly, what still can be.”Activist History Review

-

“Williams provides a vivid account of significant aspects of the [CIA] activity, informed by declassified material and rendered eminently readable by telling and energetically related anecdotes.”Survival: Global Politics and Strategy

-

“This sensational book is a gripping read, a revelation even to those … who never had any illusions about the crimes committed by the CIA in the name of ‘freedom and democracy.’”Morning Star

-

“This is a sweeping book. Williams is a careful scholar who extensively details her sources and the evidentiary bases of her findings, and is unwilling to make claims she cannot support… To Williams, I give the highest compliment I can give: I wish I had written this book!”CounterCurrents

-

“Susan Williams chronicles imperial legacies with a forensic eye, a historical mind, and a decolonial sensibility for African agency; her findings are as stunning as they are transformative.”The Windham-Campbell Prize Committee

-

“A deeply distressing history of CIA involvement in plots to eliminate certain regimes in Africa, particularly in the Congo and Ghana, just as the countries shook off European colonial rule in the mid-20th century… Rigorous reporting reveals “America’s role in the deliberate violation of democracy” in newly independent African nations.”Kirkus (Starred)

-

“What emerges from these testimonies is not a picture of tragedy, romance or against-the-odds heroism, but a sober assessment of the tough and sometimes impossible choices facing left-wing anti-colonial activists who were under pressure from foreign enemies and foreign allies alike.”The London Review of Books

-

“Beautifully written and carefully researched. It is an important contribution to the history of Africa in the context of the Cold War, when the USA and the Soviet Union were locked in a struggle for African influence and control.”Martin Plaut, former Africa editor, BBC World Service News

-

“In this masterpiece of historical analysis on the dirty tricks of the CIA in Africa during the 1960s, Susan Williams delivers her magnum opus. This richly documented narrative is based on outstanding scholarly research comprising archival sources from eight countries and the United Nations, plus numerous other written and oral sources … it could not be timelier in throwing light on the institutionalized racism and hypocrisy of Western powers.”Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja, professor of african and global studies, University of North Carolina

-

“This meticulously researched book provides a compelling account of decolonisation and the forces that sought to thwart that chaotic, protracted, but ultimately liberating process. An informative read which, in examining the death throes of the rapacious colonial project, lays bare the profound injustice imperialism inflicted on Africa and beyond.”Shashi Tharoor, author of Inglorious Empire