Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

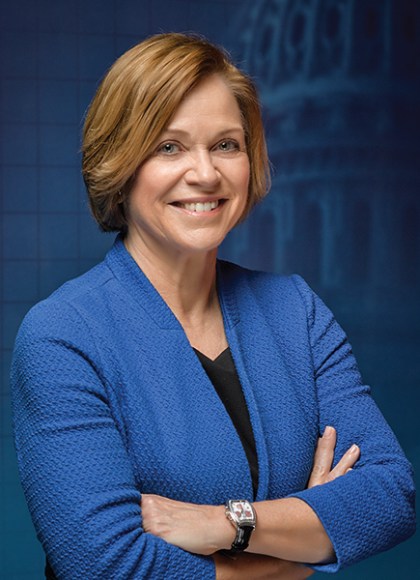

First Ladies

Presidential Historians on the Lives of 45 Iconic American Women

Contributors

By Susan Swain

By C-SPAN

Foreword by Richard Norton Smith

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 14, 2015

- Page Count

- 496 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610395670

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 14, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A look inside the personal life of every first lady in American history, based on original interviews with major historians

C-SPAN’s yearlong history series, First Ladies: Influence and Image, featured interviews with more than fifty preeminent historians and biographers. In this informative book, these experts paint intimate portraits of all forty-five first ladies — their lives, ambitions, and unique partnerships with their presidential spouses. Susan Swain and the C-SPAN team elicit the details that made these women who they were: how Martha Washington intentionally set the standards followed by first ladies for the next century; how Edith Wilson was complicit in the cover-up when President Wilson became incapacitated after a stroke; and how Mamie Eisenhower used the new medium of television to reinforce her, and her husband’s, positive public images.

This book provides an up-close historical look at these fascinating women who survived the scrutiny of the White House, sometimes at great personal cost, while supporting their families and famous husbands — and sometimes changing history. Complete with illustrations and essential biographical details, it is an illuminating, entertaining, and ultimately inspiring read.

-

"A wonderful read for anyone who loves American history, and especially the genuinely 'inside story' of the various presidencies."–Hugh Hewitt

“This chronological account engages pairs of historians--including the exceptional Carl Sferrazza Anthony--in discussing the personality, marriage, passions, and legacy of each first lady, resulting in a fluid, conversational style...This accessible account replaces stodgy depictions of stuffy, untouchable first ladies with the relatable, often tragic stories of the determined women who made it up as they went along, to the benefit of their husbands and country.”–Publishers Weekly

"An appropriate and valuable examination of the lives and roles played by the 45 women most closely identified with the U.S. presidency…In this time when the role of all women in our society is undergoing a long-overdue sea change, the collection is especially valuable as an illustration of how these women adapted to, and contributed to, the presidents whose lives they shared."–The Washington Times

“The book is a budding history buff's dream (and will likely make its readers the star of good party conversation at Mother's Day brunch).”–The Hill