Promotion

25% off sitewide. Make sure to order by 11:59am, 12/12 for holiday delivery! Code BEST25 automatically applied at checkout!

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

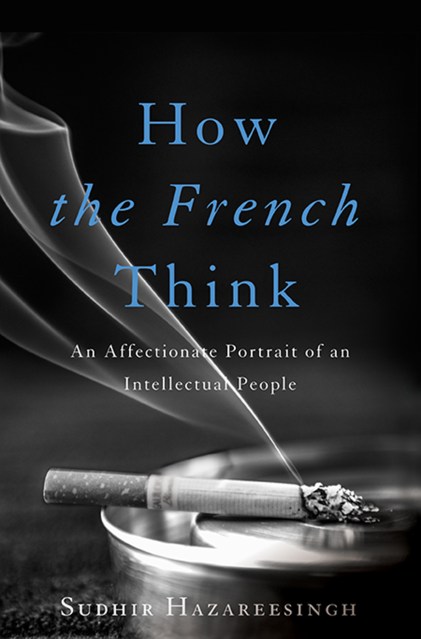

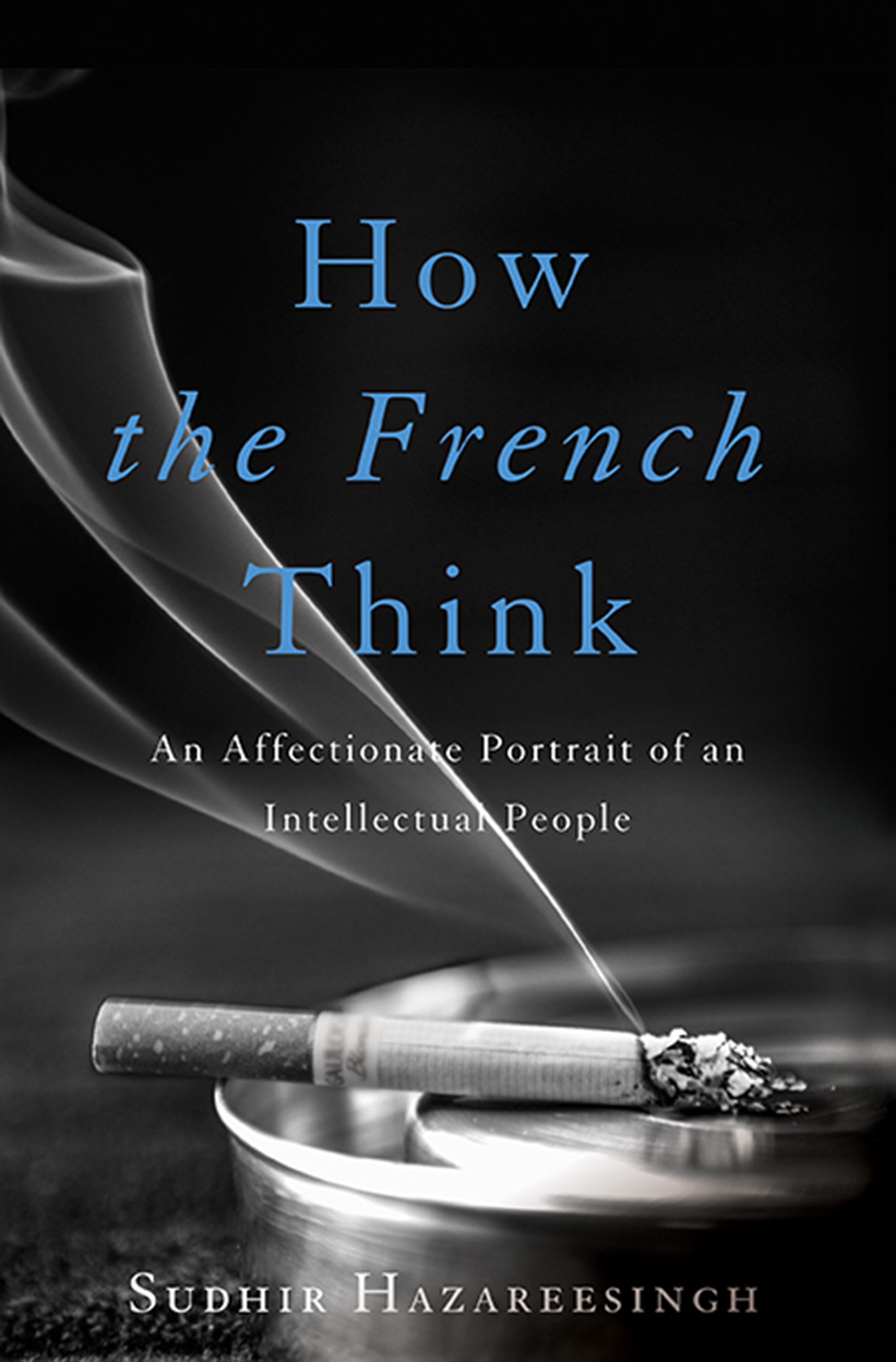

How the French Think

An Affectionate Portrait of an Intellectual People

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 22, 2015

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465061662

Price

$19.99Format

Format:

- ebook $19.99

- Hardcover $36.00

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 22, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Why are the French such an exceptional nation? Why do they think they are so exceptional? The French take pride in the fact that their history and culture have decisively shaped the values and ideals of the modern world. French ideas are no less distinct in their form: while French thought is abstract, stylish and often opaque, it has always been bold and creative, and driven by the relentless pursuit of innovation.

In How the French Think, the internationally-renowned historian Sudhir Hazareesingh tells the epic and tumultuous story of French intellectual thought from Descartes, Rousseau, and Auguste Comte to Sartre, Claude Lé-Strauss, and Derrida. He shows how French thinking has shaped fundamental Westerns ideas about freedom, rationality, and justice, and how the French mind-set is intimately connected to their own way of life-in particular to the French tendency towards individualism, their passion for nature, their celebration of their historical heritage, and their fascination with death. Hazareesingh explores the French veneration of dissent and skepticism, from Voltaire to the Dreyfus Affair and beyond; the obsession with the protection of French language and culture; the rhetorical flair embodied by the philosophes, which today’s intellectuals still try to recapture; the astonishing influence of French postmodern thinkers, including Foucault and Barthes, on postwar American education and life, and also the growing French anxiety about a globalized world order under American hegemony.

How the French Think sweeps aside generalizations and easy stereotypes to offer an incisive and revealing exploration of the French intellectual tradition. Steeped in a colorful range of sources, and written with warmth and humor, this book will appeal to all lovers of France and of European culture.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use