By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Separate and Unequal

The Kerner Commission and the Unraveling of American Liberalism

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465096084

Price

$32.00Price

$42.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $32.00 $42.00 CAD

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

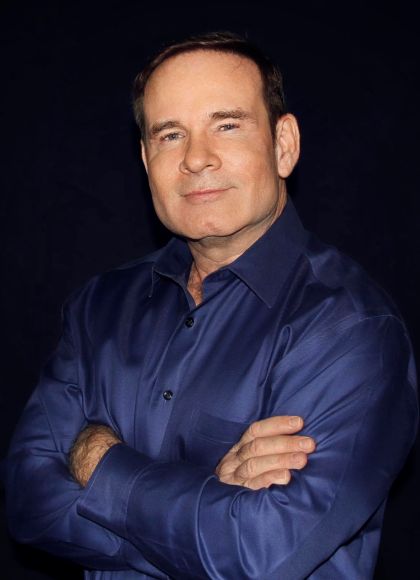

In Separate and Unequal, New York Times bestselling historian Steven M. Gillon offers a revelatory new history of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders — popularly known as the Kerner Commission. Convened by President Lyndon Johnson after riots in Newark and Detroit left dozens dead and thousands injured, the commission issued a report in 1968 that attributed the unrest to “white racism” and called for aggressive new programs to end discrimination and poverty. “Our nation is moving toward two societies,” it warned, “one black, and one white — separate and unequal.”

Johnson refused to accept the Kerner Report, and as his political coalition unraveled, its proposals went nowhere. For the right, the report became a symbol of liberal excess, and for the left, one of opportunities lost. Separate and Unequal is essential for anyone seeking to understand the fraught politics of race in America.

-

"How did a government document that black radicals anticipated would be a whitewash end up instead denouncing 'white racism'? This improbable turn of events animates Steven M. Gillon's deft, incisive, and altogether absorbing history of the Kerner Commission, which he convincingly depicts as 'the last gasp of 1960s liberalism'...Meticulous."Atlantic

-

"In Separate and Unequal, Steven M. Gillon...tells the fraught story of the commission, its recommendations and American race relations in the five decades since. His book is sophisticated, fair-minded-and a bracing corrective to complacency about racial reconciliation in America."Wall Street Journal

-

"While solutions to poverty and discrimination are far from the national political agenda, the history of the Kerner Report reminds us that liberals and the left can still influence policy from the margins."Nation

-

"Boldly written...The hard lesson being driven home by Gillon is that race relations and preservation of social decency are extraordinarily complex problems. They lack simple and immediate reconciliation. The conundrum has only grown since the Kerner Commission."New York Journal of Books

-

"[A] compelling new history of the commission.... The Kerner Commission was right about race in America, but its very ambitions enabled the backlash against much of what it hoped to achieve."Washington Post

-

"Racism remains a deeply troubling aspect of American history and culture, and Gillon's...excellent history of the 1967-68 National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, more popularly known as the Kerner Commission, provides historical insight on today's political climate...Exceptionally well-researched and timely."Library Journal (starred review)

-

"Gillon's research about the Kerner Commission, bolstered by hours of interviews with the surviving members, is extremely well-documented and also offers the feel of being ripped from today's headlines.... Well-rendered popular American history that also speaks to present-day issues."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Gillon's thought-provoking look into the Kerner Commission provides great insight into race issues of 1960s America."Publishers Weekly

-

"Steven Gillon's timely book, Separate and Unequal, is a compelling reminder that America remains a racially divided country.... Every lawmaker and every fair-minded citizen should read Gillon's history."Robert Dallek

-

"Separate and Unequal is an enormously impressive book. Steven Gillon tells a compellingly granular story about the so-called Kerner Commission's inner workings in 1967-1968.... And he employs his formidable story-telling skills to draw out the lasting historical consequences."David M. Kennedy, Donald J. McLachlan Professor of History Emeritus, Stanford University

-

"Steven Gillon delivers a riveting read about a devastating challenge to the confident liberalism of the sixties.... This fascinating book illuminates both the 1960s and our own times."Laura Kalman, professor of history, University of California, Santa Barbara

-

"Steven Gillon captures both the promise still viable in 1968 as well as the emergence of the 'post-civil rights'racial and political order that dominates American life today. It is a timely and essential book."Patricia Sullivan, author of Lift Every Voice and professor of history, University of South Carolina

-

"In our toxic and dispiriting time, Separate and Unequal is an important reminder that social and racial progress is uneven and subject to setbacks like the one suffered after the release of the Kerner Report. But Steven Gillon's surprising story of dogged liberal politicians and journalists also shows that well-framed social arguments can change the debate forever."Jonathan Alter, author of The Center Holds: Obama and His Enemiesspan

-

"When the African American freedom struggle moved north, the Great Society coalition fell apart. Fifty years on, Steven Gillon reconstructs that dramatic story with his trademark brio and deep research, chronicling both the immediate and the enduring political consequences."Gareth Davies, Associate Professor of American History, Oxford University