Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

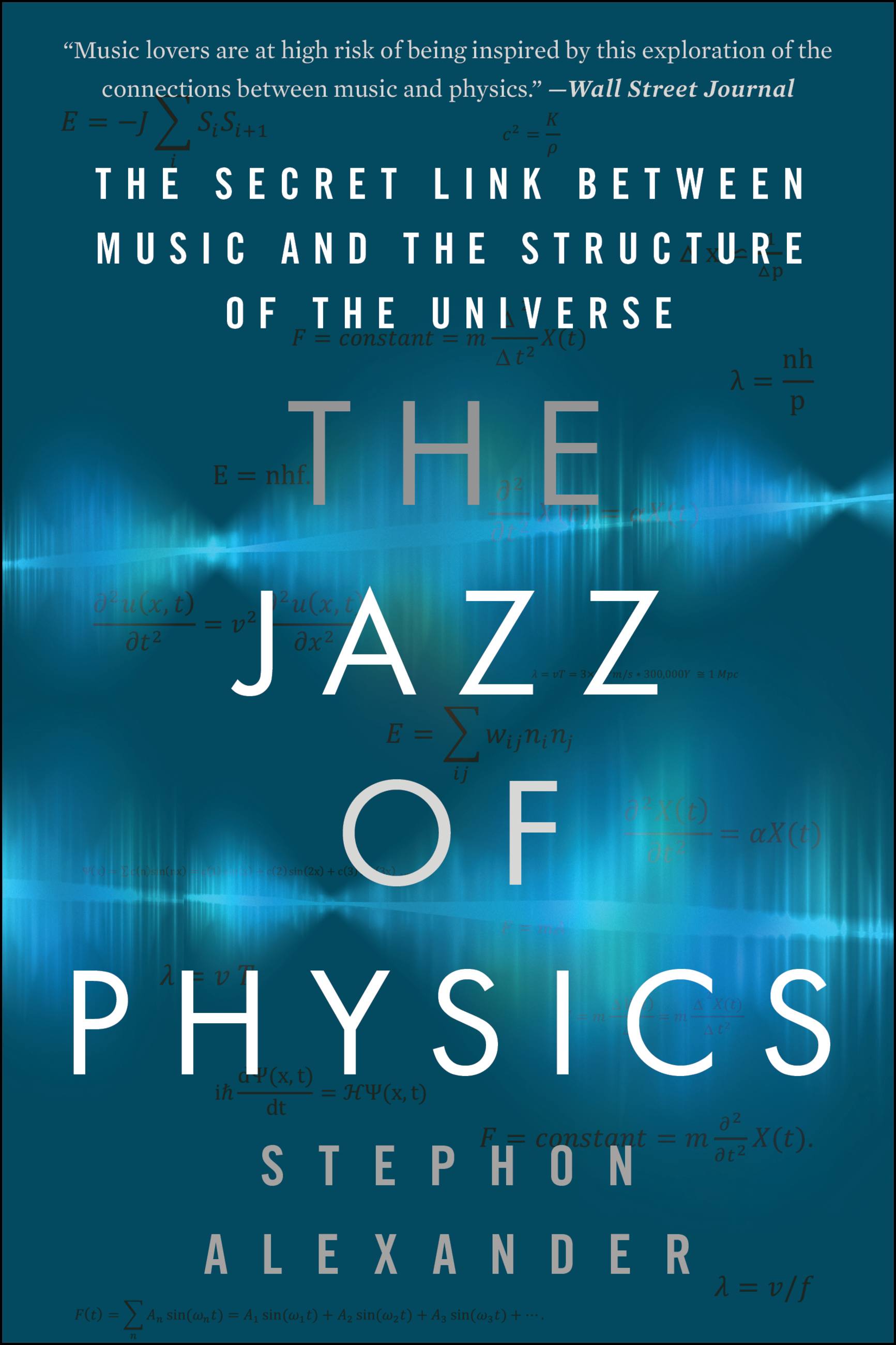

The Jazz of Physics

The Secret Link Between Music and the Structure of the Universe

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 5, 2017

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465093571

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- Digital download $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 5, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“I’ll forever be grateful to musician/physicist Stephon Alexander… He’ll help you see how our awe-inspiring universe is on a never-ending, cosmological riff.”

―Felix Contreras, NPR

More than fifty years ago, John Coltrane drew the twelve musical notes in a circle and connected them by straight lines, forming a five-pointed star. Inspired by Einstein, Coltrane put physics and geometry at the core of his music.

Physicist and jazz musician Stephon Alexander follows suit, using jazz to answer physics’ most vexing questions about the past and future of the universe. Following the great minds that first drew the links between music and physics – a list including Pythagoras, Kepler, Newton, Einstein, and Rakim – The Jazz of Physics reveals that the ancient poetic idea of the Music of the Spheres, taken seriously, clarifies confounding issues in physics.

The Jazz of Physics will fascinate and inspire anyone interested in the mysteries of our universe, music, and life itself.

-

“I’ll forever be grateful to musician/physicist Stephon Alexander… He’ll help you see how our awe‑inspiring universe is on a never‑ending, cosmological riff.”Felix Contreras, NPR

-

“Music lovers are at high risk of being inspired by this exploration of the connections between music and physics… Alexander elegantly charts the progress of science from the ancients through Copernicus and Kepler to Einstein (a piano-player) and beyond, making it clear that what we call genius has a lot to do with convention-challenging courage, a trait shared by each age’s great musicians as well.”Keith Blanchard, Wall Street Journal

-

“Interwoven with solid physics and personal anecdotes, the book does an admirable job of bringing together modern jazz and modern physics.”Physics World’s Books of the Year

-

“In the most engaging chapters of this book ‑‑ part memoir, part history of science, part physics popularization and part jazz lesson – Dr. Alexander ventures far out onto the cutting edge of modern cosmology, presenting a compelling case for vibration and resonance being at the heart of the physical structure we find around us, from the smallest particle of matter to the largest clusters of galaxies… His report on the state of research into the structure and history of the universe – his own academic field – makes for compelling reading, as does his life story.”Dan Tepfer, New York Times

-

“Alexander gives an engaging account of his uncertainties and worries as he made his way in the highly competitive world of theoretical physics, seeking to acquire the ‘chops’ needed to deal with the formidable mathematics of his day job along with those needed to solo on the sax after dark… Mr. Alexander’s rhapsodic excitement is infectious.”Peter Pesic, Wall Street Journal

-

“Marvelous.”New Scientist

-

“The book’s attempt to bring together modern jazz and modern physics strikes me as admirable… It is an intriguing comparison, and it certainly seems fresher than drawing analogies between classical music and classical physics… Time to put on some Coltrane and riff some new research ideas?”Trevor Cox, Physics World

-

“Alexander’s book, The Jazz of Physics, explores the resonance between science and music to a depth that far surpasses other works on the same concept.”New Criterion

-

“Groundbreaking… Alexander illustrates his points with colorful examples, ranging from the Big Bang to the eye of a galactic hurricane.”Down Beat

-

“Alexander’s account of his own rise from humble beginnings to produce contributions to both cosmology and jazz is as interesting as the marvelous connections he posits between jazz and physics.”Publishers Weekly

-

“In this loosely autobiographical meditation, Alexander explores resonances between music and physics in Pythagoras’s ‘music of the spheres,’ Albert Einstein’s love of music, Coltrane’s love of Einstein, and his own ideas as a theoretical physicist and jazz saxophonist. It’s a vast, cosmic theme that includes quantum mechanics, superstring theory, the Big Bang, the evolution of galaxies, and the process of scientific theorizing itself… Alexander’s enthusiasm for his subject is infectious.”Kirkus

-

“This book could just as well be called The Joy of Physics because what leaps out from it is Stephon Alexander’s delight and curiosity about the cosmos, and the deep pleasure he finds in exploring it. True to the jazz he loves so much, Stephon is an intellectual improviser riffing with ideas and equations. It's a pleasure to witness.”Brian Eno, artist, composer, and producer

-

“The Jazz of Physics is a cornucopia of music, string theory, and cosmology. Stephon takes his reader on a journey through hip hop, jazz, to new ideas in our understanding of the first moment of the big bang. It is a book filled with passion, joy and insight.”David Spergel, Princeton University

-

“A riveting firsthand account of the power of intuitive and unconscious in the process of scientific discovery. Being both top-notch physicist and jazz musician, Stephon Alexander has a unique voice. Listening to him, you will hear the music of the Universe.”Edward Frenkel, author of Love and Math

-

“Stephon Alexander takes us along on his twinned quest to discover the fundamental principles of physics and of jazz performance and composition. He is a great storyteller and he paints vivid portraits of the masters of music and science who guide him on his search, which leads to a revelation of a common pattern and symmetry in the universes created by John Coltrane and Albert Einstein. If you spend one evening of your life contemplating the relationship between art and science, spend it with this book.”Lee Smolin, author of The Trouble with Physics

-

“Is the universe a musical instrument that plays itself? It is according to Stephon Alexander, a string theorist who shares his journey from a crime ridden junior high school to the upper echelons of physics and jazz. Moving fluidly from T dualities to John Cage, he tells how his two worlds blended together like a stereoscopic vision-a sonic cosmos where Einstein and Coltrane naturally meet, and where intuition and improvisation are as important as technique. Whether he's hanging with Brian Eno or Brian Greene, Alexander never loses sight of the math or the melodies, never condescends to his reader but rather uses his own childlike awe and personal charm to take us into the details of chords and equations. It's impossible to resist following him as he ‘solos with the equations of D-branes’ on paper napkins in jazz clubs, searching for the eloquent underlying harmonies that brought the universe (and us) into being”KC Cole, author of Something Incredibly Wonderful Happens

-

“Music, physics and mathematics have lived in tune since Pythagoras and Kepler, but Prof. Alexander’s book creates a new and powerful resonance, coupling the improvisational world of Jazz to the volatile personality of quantum mechanics, and making the frontiers of cosmology and quantum gravity reverberate like in no other book.”João Magueijo, author of Faster Than the Speed of Light

-

“In this very creative work Stephon Alexander leads us through his remarkable journey from jazz musician to theoretical physics, from the music of the spheres to string theory.”Professor Leon N. Cooper, Laureate of the Nobel Prize in Physics

-

“Stephon Alexander has written an entertaining and important book about how science is becoming more like improvised music. Young musicians and scientists will find a deeper way to connect with their work in its pages. There is also a message about scientific progress: It isn’t just about a sterile quest to make a better equation, but also the struggle to build deeper connections between people and between us and the universe at large.”Jaron Lanier, author of Who Owns the Future?