By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

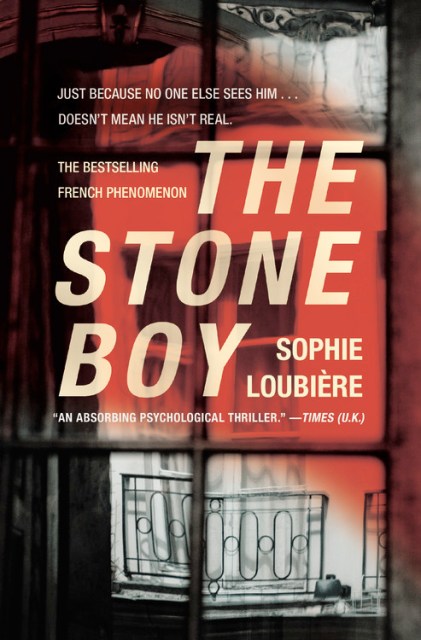

The Stone Boy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 8, 2014

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455547623

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 8, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

When Madame Préau returns to her own house outside Paris after several years spent in a convalescent home, she immediately notices that the neighborhood has changed. Now, instead of a beautiful garden next door there is a new house. And she can see directly into her new neighbors’ windows.

Madame Préau quickly feels that something isn’t right. Her neighbors have two perfectly healthy children who play in the yard after school. But there is also a third child: a young boy who looks malnourished and abused, and tosses small stones at her window in an apparent call for help. The family denies his existence.

But is the little boy real, or merely a hallucination of a lonely, mentally unstable old woman cut off from her own beloved grandson?

When the police refuse to listen to her, Madame Préau decides to take matters into her own hands. She’s determined to help the little boy, and she’ll do anything to make sure he’s safe…

-

"Translated in a deliciously forthright style by Nora Mahony, The Stone Boy mischievously toys with the reader's expectations, blending elements from the traditional mystery tale with those of the paranormal...The irascible and irrepressible Madame Préau makes for a delightfully ambiguous protagonist, and Loubiere deftly plots a compelling tale that is as poignantly heartbreaking as it is thrilling."Irish Times

-

"A creepy psychological thriller....Is the boy real? Is Martin a loyal son or a conspirator? The truth is as chilling as the rest of this unsettling tale."Publishers Weekly

-

"You'll distrust your own dog after you read this clever entrapment.... Buy this book, or make sure your library buys it. It's a good read with the promise of long shelf life."The Durango Herald

-

"[Loubiere] pulls off a few nifty tricks and surprise twists that should outsmart readers who think they can guess the ending...If her other novels are as entertaining as THE STONE BOY, she deserves a loyal following."Richmond Times-Dispatch

-

"You may wonder, how interesting is a story about an old lady that thinks she sees a small boy outside her window? Let me put it this way: my jaw is still on the floor. Even after finishing THE STONE BOY, I have no idea how Sophie Loubière pulled it off-every page was interesting; every page held my attention.... What you'll read will hover in your mind long after the final page is closed."The Avid Reader

-

"An absorbing psychological thriller."The Times (UK)

-

"Impossible to put down."La Semaine

-

"A suspenseful psychological thriller, The Stone Boy is also a beautiful picture of a passionately loving grandmother, an unreliable old lady, more nosy and intrusive than Miss Marple."Françoise Chandernagor

-

"This book is a real gem full of creativity, humour and suspense...with an unforgettable heroine."Le Nouvel Observateur

-

"A thoroughly menacing psychological thriller."Morning Star (UK)

-

"A novel as complex as a spider's web."Le Dauphiné Libéré

-

"An intriguing story - one that lingers after the last page is read.... A truly wonderful read."BookLoons

-

"On the evidence of this atmospheric and complex thriller, France is shaping up as a font of impressive new crime writers specialising in unorthodox and genuinely unsettling narratives. . . French Noir is in the ascendant."Financial Times (UK)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use