By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

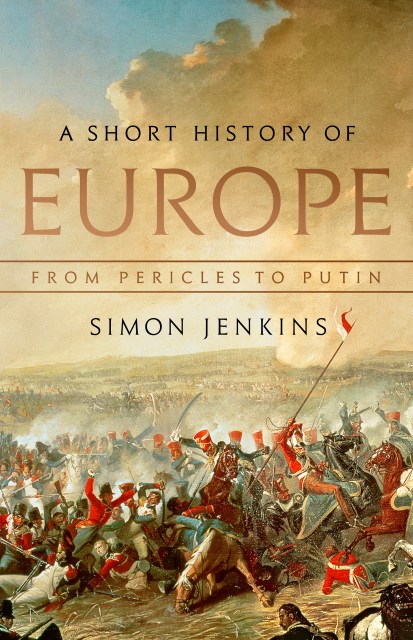

A Short History of Europe

From Pericles to Putin

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 5, 2019

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541788534

Price

$12.99Format

Format:

- ebook $12.99

- Hardcover $38.00

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 5, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In just a few hundred years, a modest peninsula off the northwest corner of Asia has seen the rise and fall of several empires; served as the crucible for scientific dynamism, cultural innovation, and economic revolution; and witnessed cataclysms and bloodshed that have almost destroyed it several times over. This is Europe: a continent whose identity emerged not so much by virtue of geographic or ethnic continuity, but by a long and storied struggle for power.

Studded with infamous figures–from Caesar to Charlemagne and Machiavelli to Marx–Simon Jenkins’s history of Europe travels briskly from the Roman Empire, the Dark Ages, and the Reformation through the French Revolution, the World Wars, and the fall of the USSR. What emerges in this thrilling and expansive telling is a continent as defined by its continually clashing cultural identities and violent crises as it is by its tireless drive for a society based on the consent of the governed — which holds true right up to the present day.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use