Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

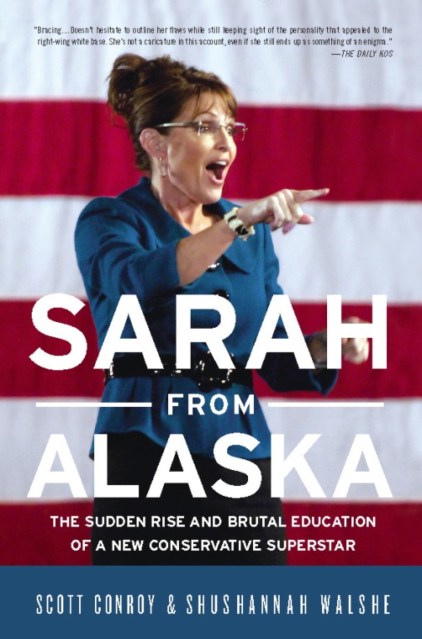

Sarah from Alaska

The Sudden Rise and Brutal Education of a New Conservative Superstar

Contributors

By Scott Conroy

By Shushannah Walshe

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 3, 2009

- Page Count

- 290 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9780786746286

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 3, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Sarah from Alaska illuminates both the talents that helped make Palin a superstar and the traits that became liabilities under the intense pressures of a divisive national campaign. It reveals in riveting detail how Palin’s vice presidential campaign became as dysfunctional as it was secretive, explores the circumstances behind her triumphs and baffling missteps, and provides new context for understanding her values, her political successes in Alaska, and her abrupt resignation from the governorship.

“It’s easy to turn Sarah Palin into a caricature of either a heroic everywoman or ridiculous dolt,” the authors say, “but the truth is that she is more complex than either her most passionate defenders or harshest critics give her credit for.” Palin remains ambitious and enormously popular among social conservatives, and her future will be intrinsically interwoven with that of the Republican Party as it struggles to redefine itself and recapture the necessary margin for national political victory in the next decade. That makes Sarah from Alaska essential reading for anyone interested in American politics.