Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

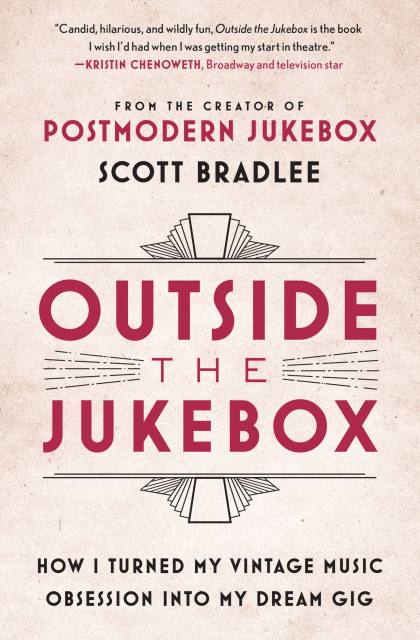

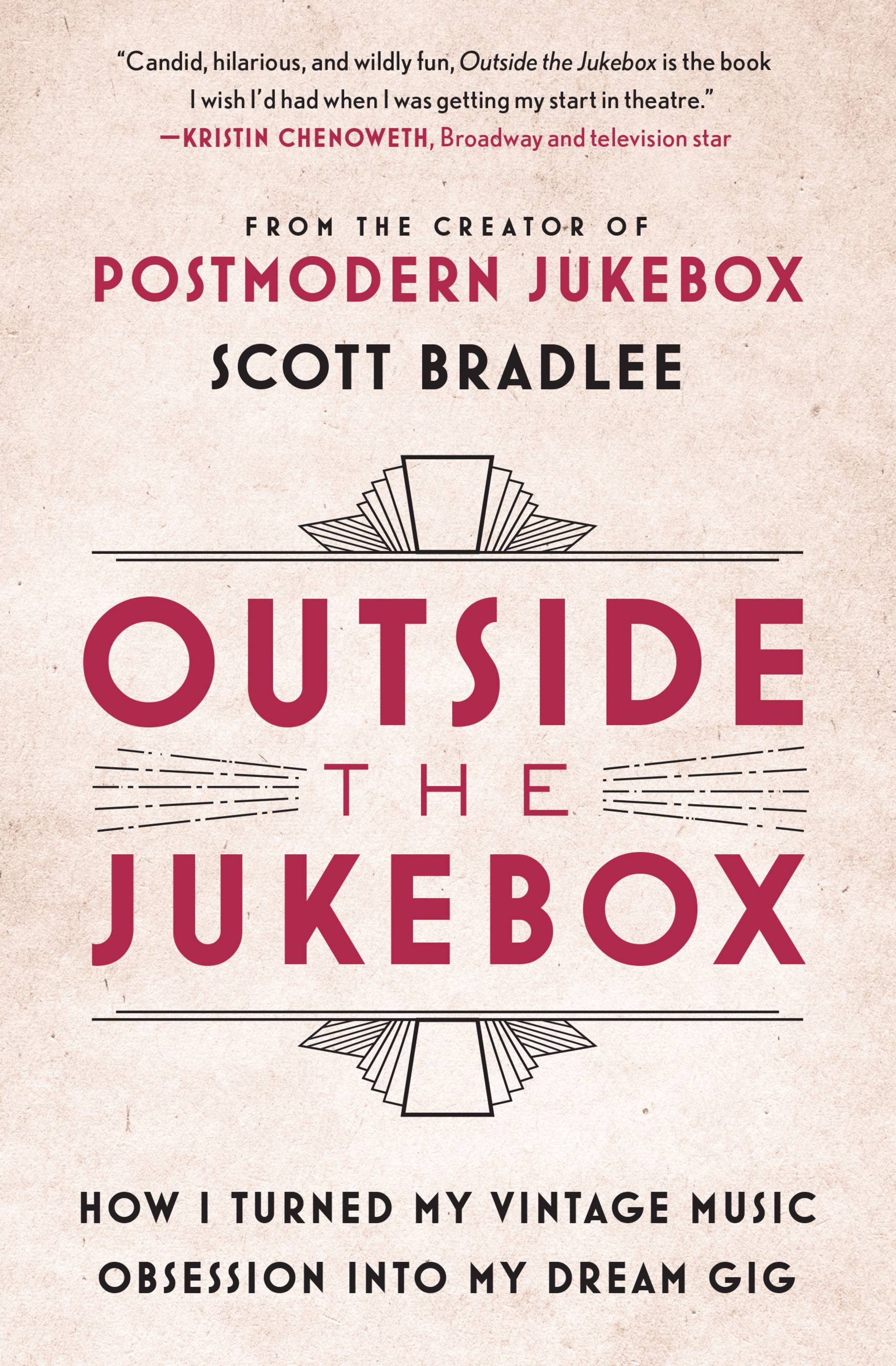

Outside the Jukebox

How I Turned My Vintage Music Obsession into My Dream Gig

Contributors

Read by Scott Bradlee

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 12, 2018

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549113437

Price

$24.98Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.98

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 12, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

With student loan debt piling up and no lucrative gigs around the corner, Scott Bradlee found himself in a situation all too familiar to struggling musicians and creative professionals, unsure whether he should use the little income he had to pay his rent or to avoid defaulting on his loans. It was under these desperate circumstances that Bradlee began experimenting, applying his passion for jazz, ragtime, and doo wop styles to contemporary hits by singers like Macklemore and Miley Cyrus–and suddenly an idea was born.

Today, Postmodern Jukebox — the rotating supergroup devoted to period covers of pop songs, which Bradlee created in a basement apartment in Queens, New York–is a bona fide global sensation, having collected more than three million subscribers on YouTube while selling out major venues around the world and developing previously unknown talent into superstar singers. From its Etta James-inspired rendition of Radiohead’s “Creep” to its New Orleans jazz interpretation of Meghan Trainor’s “All About That Bass,” the group has established a sound like no other, crafting hits as exquisitely sublime as they are humorously absurd.

But it wasn’t always as easy as the YouTube videos make it look. As he worked to establish Postmodern Jukebox, Bradlee struggled through the obstacles that every self-employed artist or entrepreneur with a vision faces: how to collaborate successfully on teams with divergent visions, how to outrun the naysayers, how to chase the next innovation when your reputation makes others start to pigeonhole you, and so many of the other challenges lining the path to success.

Taking readers through the false starts, hilarious backstage antics, and unexpected breakthroughs of Bradlee’s journey from a lost musician to a musical kingmaker — and presenting all the entrepreneurial insights he learned along the way — Outside the Jukebox is an inspiring memoir about how one musician found his rhythm and launched a movement that would forever change our relationships to our favorite songs.

-

"Candid, hilarious, and wildly fun, Outside the Jukebox is the book I wish I'd had when I was getting my start in theatre."Kristin Chenoweth, Broadway and television star

-

"Bradlee found tremendous success by going his own way, and he turned his passion into a creative movement....I am learning from this read!"Mick Fleetwood, cofounder of Fleetwood Mac

-

"Bradlee's story is a crash course on how to launch a monster career in entertainment."Chris Silbermann, managing director, ICM Partners

-

"Scott Bradlee may just be the most creative musician turned entrepreneur I've had the honor to work with. Read this book and you will be inspired to chase your dreams the way he has."John Burk, president, Concord Records

-

"Outside the Jukebox will be of interest to up-and-coming musicians and Internet performers, not least because of his description of the traits and habits that helped Bradlee flourish....Here's hoping that Bradlee's hunger for success and his love of music keep him producing joyous, winning work for many years to come."The Weekly Standard

-

"With an uncanny ability to tap into the cultural zeitgeist time and again, Scott Bradlee has given rise to a whole new crop of mega-talented singers and musicians, blending pop and jazz in a completely novel way....Outside the Jukebox takes us inside his unique method."Dave Koz, jazz saxophonist and host of Sirius-XM's The Dave Koz Lounge

-

"Fans of Postmodern Jukebox will certainly enjoy this, but anyone who is ready, as Bradlee says, to 'go out and make art' will appreciate his optimistic tone as well...Outside the Jukebox is a feel-good memoir with an inside look at Postmodern Jukebox founder Scott Bradlee's unconventional approach to a career."Shelf Awareness (starred review)

-

"[An] entertaining memoir...Anyone eager to know more about the man behind the music will want to pick this up."Publishers Weekly