By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

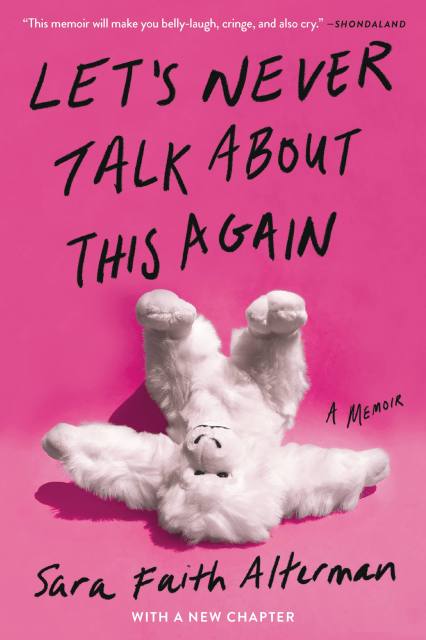

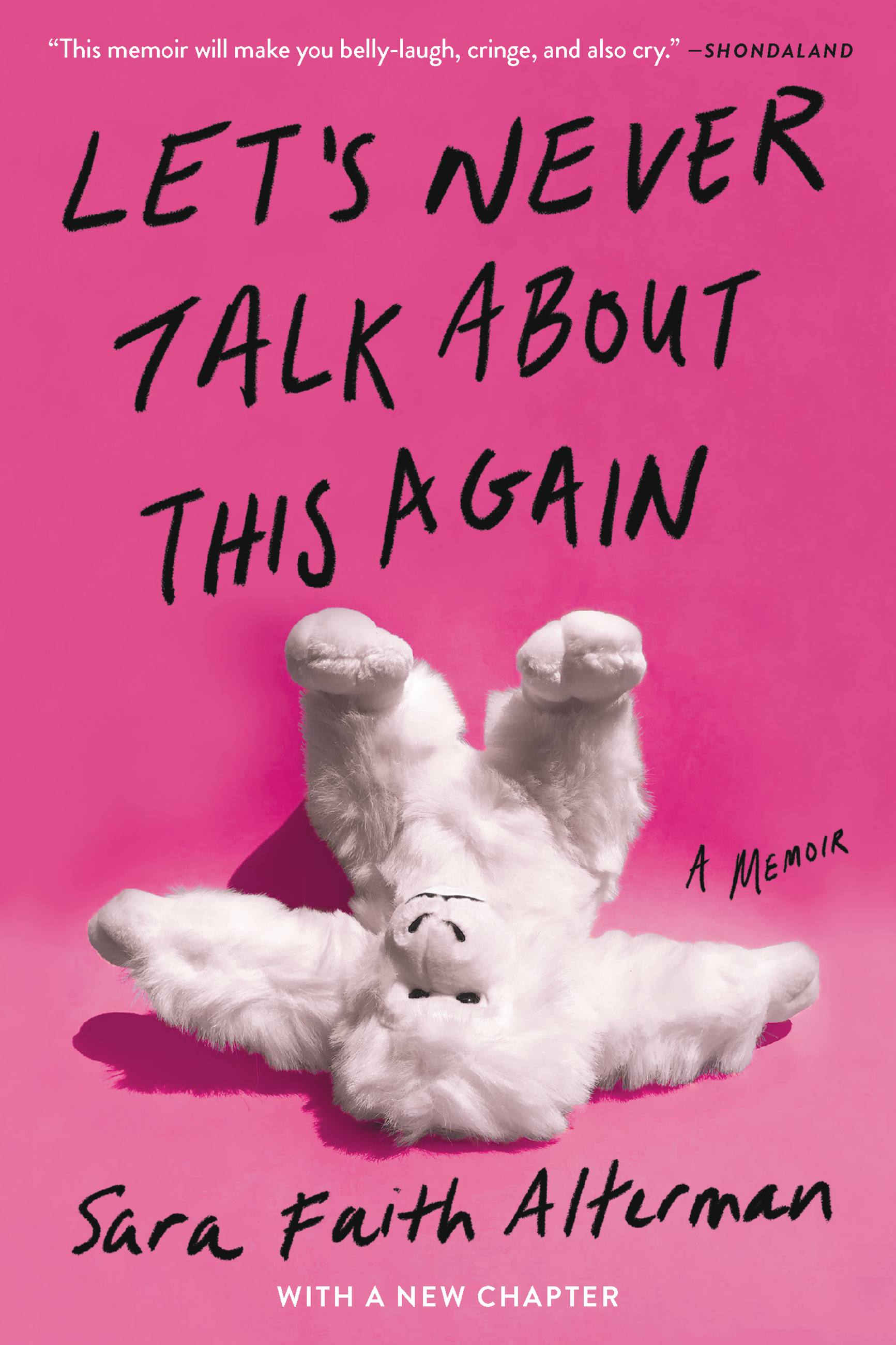

Let’s Never Talk About This Again

A Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 8, 2022

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538748664

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 8, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Twelve-year-old Sara enjoyed an G-rated existence in suburban New England, filled with over-the-top birthday cakes, Revolutionary War reenactments, and nerdy word games invented by her prudish father, Ira. But Sara’s world changed for the icky when she discovered that Ira had been shielding her from the truth: that he was a campy sex writer who’d sold millions of books in multiple languages, including the wildly popular Games You Can Play with Your Pussy. Which was, to the naïve Sara’s horror, not a book about cats. For decades the books remained an unspoken family secret, until Ira developed early onset Alzheimer’s disease . . . and announced he’d be reviving his writing career. With Sara’s help.

In this cringeworthy, hilarious, and moving memoir, Sara shares the profound experience of discovering new facets of her father; once as a child, and again as an adult. Let’s Never Talk About This Again is a must-read confessional from a woman who spent years trying to find humor in the perverse and optimism in the darkness, and succeeded.

-

“Alterman balances the squeaminess with self-deprecation and humor, moving between vulnerability and poised funny storytelling. . . There are crushing scenes and excruciating awkwardness, and a depth of heart, sensitivity, and respect in this sharp-warm exploration of the importance of uncomfortable conversations and how love can still happen after them.”Boston Globe

-

"[Alterman] writes hilarious, dark, and touching prose, creating that right level of cringe to inspire others to tell their own problematic childhood stories (baby boomers be damned)."Chicago Review of Books

-

"Alterman is a top-notch comic writer, and fans of Chris Offutt's memoir My Father the Pornographer or the podcast "My Dad Wrote a Porno" will especially love this smart, compelling chronicle of family connections and the foibles and contradictions that make us human."BookPage

-

"Alterman leavens some heavily emotional subject matter with a razor-sharp sense of humor that will help readers smile through the more painful passages... A vividly written, compassionate homage to a beloved and eccentric parent."Kirkus

-

"[A] funny, tender, and compassionate narrative in which Alterman-while living and working on the West Coast and starting her own family-helps her parents navigate this new phase of Ira's life amid his declining mental capabilities due to Alzheimer's."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

“[F]ull of dark humor.”BookRiot

-

"[Let's Never Talk About This Again] tenderly explores family dynamics and the pain of loss as well as the nuances of humiliation."Time

-

"A memoir that includes stories about writing sex books with her once-prudish father might sound hilarious, which it is, but Let's Never Talk About This Again is so much more. It's also a sweet, tender, and heartbreaking sendoff to her dad that's full of so much humor and love it's almost impossible not to smile, then laugh, then eventually cry."Dan Marshall, author of Home Is Burning and Life Hacks for Dads

-

"It's a little ironic given the title but Let's Never Talk About This Again tackles difficult topics with warmth, candor, and humor. Sara Faith Alterman explores the biggest topics, literally ranging from love and birth to loss and death with intimacy and charm and the exact right number of references to Dunkin' Donuts. Every chapter gleams with a skill and level of perspective that make me think: 'What a great brain she has! I'm so glad she squeezed this book out of it!'"Josh Gondelman, Emmy Award-winning writer, comedian, and author of Nice Try: Stories of Best Intentions and Mixed Results

-

"Page after page of the most hilarious and heartwarming honesty. Sara Faith Alterman turns cringeworthy surprises in family life into sweet comedy gold."Kevin Allison, creator of the RISK! podcast

-

"A laugh-cry memoir about family myths, unreliable narrators, and forgiveness. Alterman's story about her father is packed with empathy, honesty, and the sharpest New England humor."Meredith Goldstein, author of Can't Help Myself: Lessons and Confessions From a Modern Advice Columnist

-

“This memoir will make you belly-laugh, cringe, and also cry, as Sara navigates a new, simultaneously surreal and grief-strewn world she finds herself in.”Shondaland

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use