Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

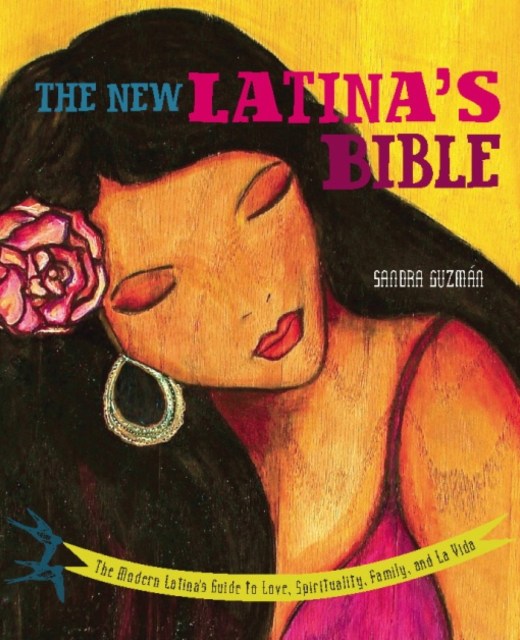

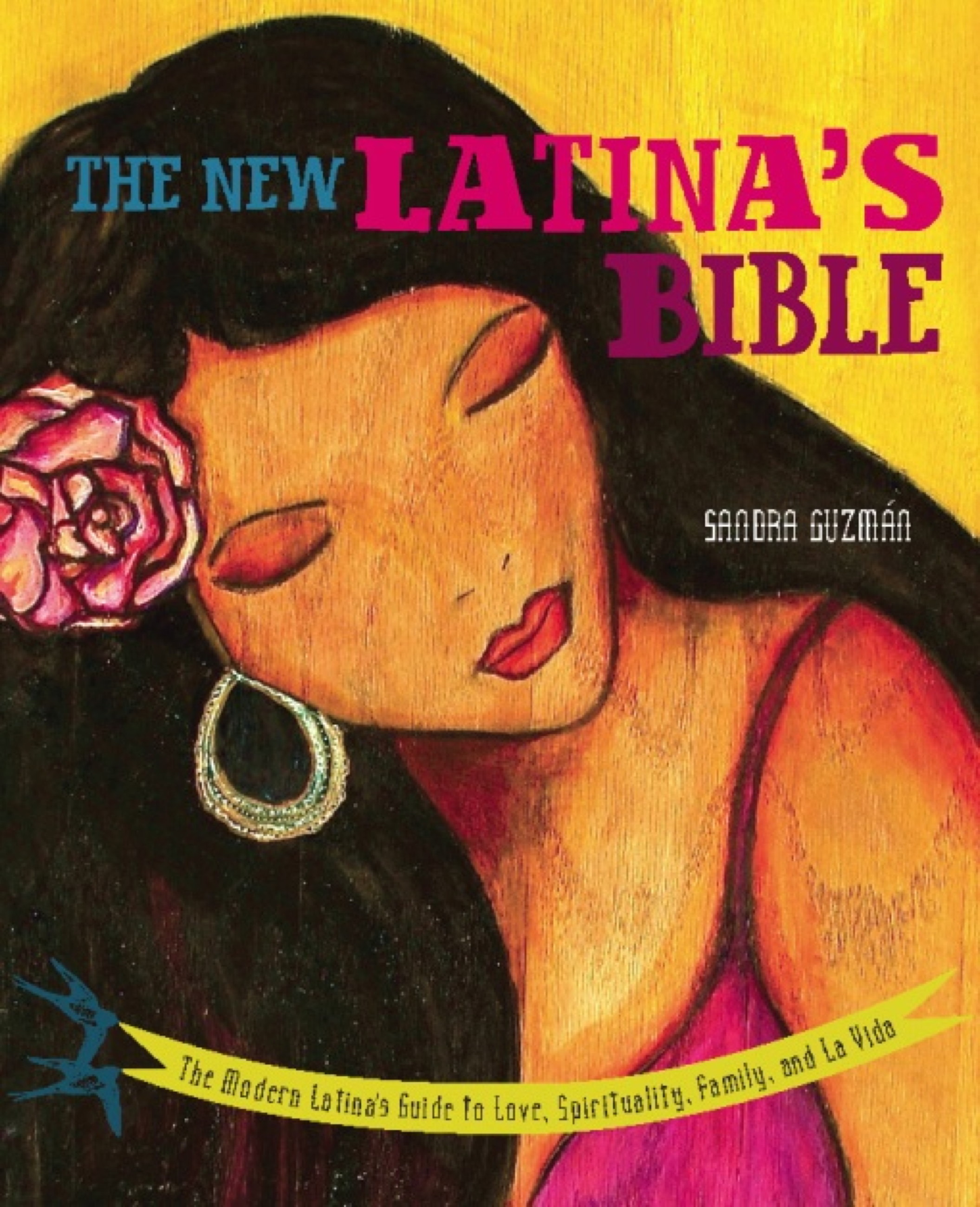

The New Latina’s Bible

The Modern Latina's Guide to Love, Spirituality, Family, and La Vida

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 3, 2011

- Page Count

- 450 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580054058

Price

$13.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

For nearly a decade, The Latina’s Bible has been the go-to guide for Latinas everywhere. In this updated and expanded edition, author Sandra Guzman continues to use her trademark warmth, humor, and wisdom to explore a wide range of topics, from dating and sexuality to family and career. The New Latina’s Bible charts new territory, adding chapters that cover important issues such as sexual abuse, domestic and dating violence, interracial love, and gender identity. Guzman once again provides a hip, empowering, highly readable guide for women who are facing the trials and joys of living and loving as twenty-first century Latinas.

-

"Hip and chatty, with serious undertones, this 'bible' will be a valuable resource for young Latina women. Guzman tackles media image versus self-image up front; she rejects the bureaucratic term 'Hispanic' and celebrates the infinite variety of skin color, body shape, hair texture, regional dialect and national origin of today's Latinas as she shares personal anecdotes and advice on a wide range of modern conundrums..."Publishers Weekly

-

"Showing readers how to balance traditional values with new American ways, [Guzman] fills every page with interesting sidebars, including facts, statistics, short biographies, web sites, and bibliographies. Incorporated into the treatment of these issues are frank discussions of sexual abuse, gender inequality, and what it means to be homosexual in the Latin community. Few if any current titles embrace those concerns."Library Journal