Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

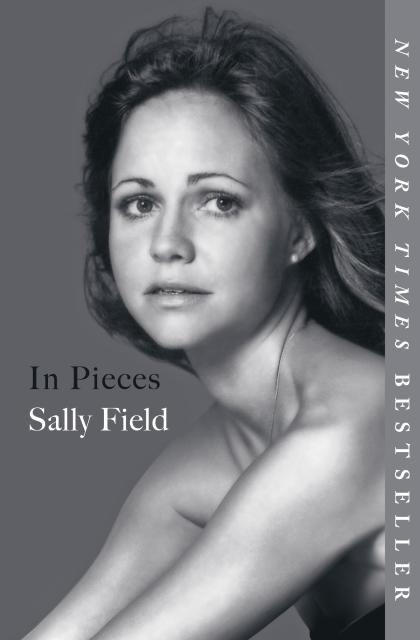

In Pieces

Contributors

By Sally Field

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 15, 2019

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538763032

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover (Large Print) $44.00 $55.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 15, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

One of the most celebrated and beloved actors of our time, Sally Field has an infectious charm that has captivated the nation for more than five decades. From the dazzling complexity of Sybil, to the Academy Award-winning performances in Norma Rae and Lincoln, Field has stunned audiences time and time again with her artistic range and emotional acuity. Yet there is one character who always remained hidden: the shy and anxious little girl within.

With raw honesty, humility, and authenticity her fans have come to expect, Field brings readers behind-the-scenes for not only the highs and lows of her star-studded early career in Hollywood, but deep into the truth of her lifelong relationships–including her complicated love for her own mother.

Powerful and unforgettable, In Pieces is an inspiring account of life as a woman in the second half of the twentieth century.

-

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER

-

"A classic in the making - the kind that will land on the bestseller list...and stay on shelves for years to come."Boris Kachka, New York Magazine

-

"Field fuels this aching, lyrical memoir with frankness about her emotional childhood, her conflicted relationship with the late Burt Reynolds, and how acting helped her interpret life in all its pain and beauty."Entertainment Weekly

-

"I adored Sally Field's recent memoir, In Pieces. Although it deals with really heavy subject matter - sexual violence, childhood trauma - which made me step away for a break at times, her writing is so captivating. It brings you right into the moment, even moments that took place decades ago, and brings you along on her journey of admitting truths to herself about all of the trauma she has experienced. Her descriptions of acting - as her emotional release, her true love, her craft - were beautiful, especially interwoven with what was occurring in her personal life. What a remarkable woman. (PS: This book made me call my mom and thank her for being my mom.)"Buzzfeed

-

"A memoir as soulful, wryly witty, and lyrical as it is candid and courageous... Eye-opening and deeply affecting... Arresting in its dark disclosures, vitality, humour, and grace, Field's deeply felt and beautifully written memoir illuminates the experiences and emotions on which she draws as an exceptionally charismatic, empathic, and powerful artist."Booklist

-

"Field holds nothing back...This powerful, timely narrative resonates with pain and triumph."Library Journal, Best Books of 2018

-

"A complex cri de coeur [and] shockingly frank...A rarity in the world of celebrity memoirs."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}USA Today

-

"Clarity and Grace Shine Through the Darkness in Sally Field's Memoir... If you come to "In Pieces," expecting to meet a plucky Sally Field desperate to be liked, you will not find her. Written by the actor over seven years, without the aid of a ghostwriter, this somber, intimate and at times wrenching self-portrait feels like an act of personal investigation - the private act of a woman, now 71, seeking to understand how she became herself, and striving to cement together the shards of her psyche that have been chipped and shattered over the course of her life..."In Pieces" serves as a kind of tribute to women - her mother in particular - and others who would guide and protect Field throughout her turbulent childhood and an adulthood fraught by personal and professional upheaval."New York Times Book Review

-

"Award-winning actress Sally Field could have written a typically dishy Hollywood memoir. But her book, In Pieces, is an intensely personal, vulnerable accounting of her life and career. Field's meditations on memory, fear and love will leave you shattered. Her lyrical prose and sly humor will glue you back together again."NPR, Best Books of 2018

-

"Raw and revealing...In her book, seven years in the writing, [Field] examines the complex relationship with her "perfectly imperfect" mother, Margaret. That is the thread that holds her story together: the woman who often held her together....[Sally Field] is not a woman who will keep quiet any longer. And that's a good thing. She still has a lot to say."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; font: 11.0px Helvetica; color: #323333}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}AARP

-

"Beyond the headlines...there's a smart woman's reckoning with her complicated past."People

-

"Fantastic."Chicago Tribune

-

"Field tells her story with such affecting literary depth...with IN PIECES, she comes to them beautifully."Entertainment Weekly

-

"'In Pieces' is the opposite of a self-aggrandizing, celebrity biography meant to cement one's place in history. Rather, it's a vulnerable, frank, almost voyeuristic view inside Field's mind and her efforts to "piece" together her life's most crucial moments into a coherent understanding of who she is as a human being."Atlantic Journal-Constitution

-

"Do you ever put off reading a book because it will come to an end? "In Pieces" hung around my bedroom for a week. Not surprisingly, it is as delightful as Field is."The Florida Times-Union

-

"In Pieces is extraordinary....raw, brutally honest, introspective."Pajiba

-

"Talented and versatile Academy and Emmy Award-winning actor Field's credits range from Gidget and Sybil to Norma Rae and Places in the Heart, among many others. Now she reveals the personal side of her story, along with her rise to fame. Reverberating throughout these pages is the impact of sexual abuse by her stepfather and her struggles to work through her relationship with her beloved mother. Field addresses these issues frankly, as she does the complex facets of her marriages and other associations (including her much-publicized relationship with actor Burt Reynolds), as well as various episodes in her behind-the-scenes professional life. Her discussion of building a vibrantly enduring acting career in the midst of turbulence is especially fascinating. There are vivid anecdotes from on and off the set, well-drawn accounts of priceless tutelage by famed Lee Strasberg, and powerful depictions of how Field crafted major dramatic roles from deep within her emotional reservoir. It is all here and in Field's inimitable words, enhanced by thoughtfully chosen photographs.Library Journal

VERDICT Especially relevant in light of the growing awareness of rape and sexual assault, this engrossing, well-written work will appeal to fans and those previously unfamiliar with Field's work." -

"A reminder that telling your truth can help you heal."Chicago Tribune

-

"Sally Field who, at 71, has ripped herself open and written one of the most exposing memoirs I have ever read. A memoir so honest and authentic it could not be more right for now if it had been produced by a trend forecaster algorithm. But, in fact, the timing is pure coincidence..With a career like hers behind her, she could have put her feet up and lived off the proceeds, keeping her girl/granny next door image intact, could have signed off on a production-line celebrity biography and people would have read it. Instead, she...fully exposed herself in her memoir... and, in so doing, put herself front and centre of the very urgent conversation we're having right now about gender."The Pool

-

"Field lays it all on the line...In Pieces is an indelible portrait of a woman we all thought we knew."Auburn Citizen