By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

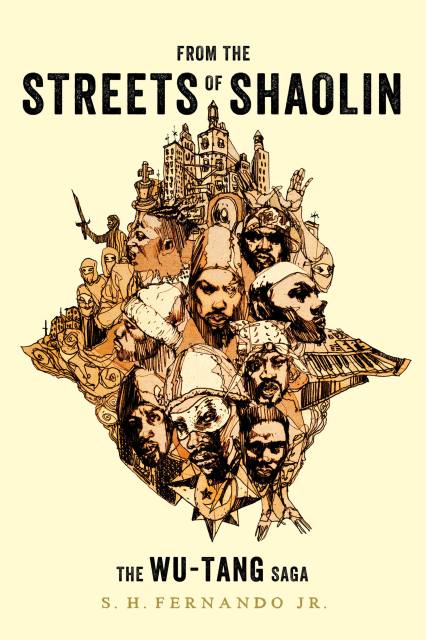

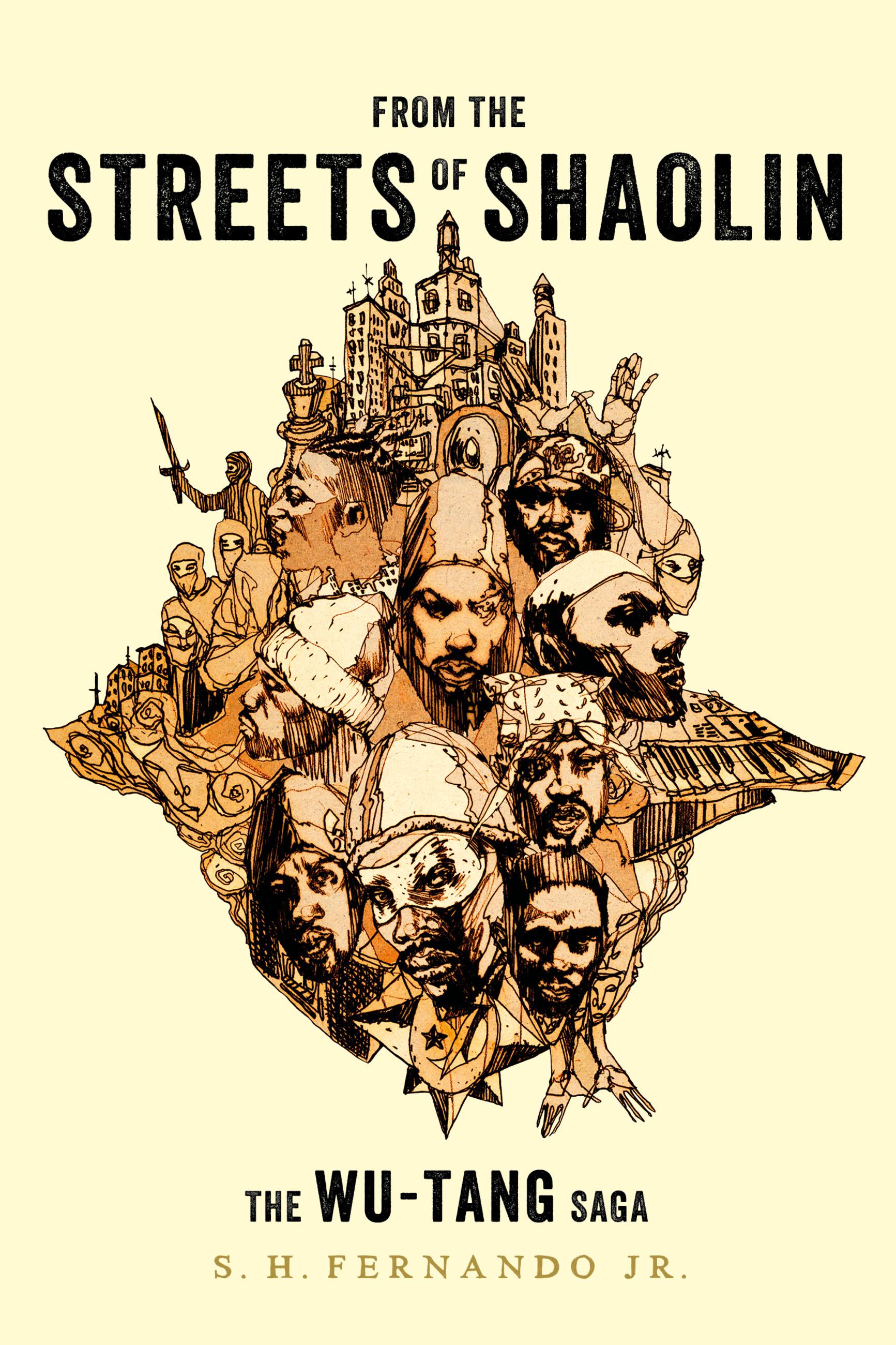

From the Streets of Shaolin

The Wu-Tang Saga

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 6, 2021

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780306874444

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 6, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This definitive biography of rap supergroup, Wu-Tang Clan, features decades of unpublished interviews and unparalleled access to members of the group and their associates.

This is the definitive biography of rap supergroup and cultural icons, Wu-Tang Clan (WTC). Heralded as one of the most influential groups in modern music—hip hop or otherwise—WTC created a rap dynasty on the strength of seven gold and platinum albums that launched the careers of such famous rappers as RZA, GZA, Ol' Dirty Bastard, Raekwon, Ghostface Killah, Method Man, and more. During the ‘90s, they ushered in a hip-hop renaissance, rescuing rap from the corporate suites and bringing it back to the gritty streets where it started. In the process they changed the way business was conducted in an industry known for exploiting artists. Creatively, Wu-Tang pushed the boundaries of the artform dedicating themselves to lyrical mastery and sonic innovation, and one would be hard pressed to find a group who's had a bigger impact on the evolution of hip hop.

S.H. Fernando Jr., a veteran music journalist who spent a significant amount of time with The Clan during their heyday of the ‘90s, has written extensively about the group for such publications as Rolling Stone, Vibe, and The Source. Over the years he has built up a formidable Wu-Tang archive that includes pages of unpublished interviews, videos of the group in action in the studio, and several notepads of accumulated memories and observations. Using such exclusive access as well as the wealth of open-source material, Fernando reconstructs the genesis and evolution of the group, delving into their unique ideology and range of influences, and detailing exactly how they changed the game and established a legacy that continues to this day. The book provides a startling portrait of overcoming adversity through self-empowerment and brotherhood, giving us unparalleled insights into what makes these nine young men from the ghetto tick. While celebrating the myriad accomplishments of The Clan, the book doesn't shy away from controversy—we're also privy to stories from their childhoods in the crack-infested hallways of Staten Island housing projects, stints in Rikers for gun possession, and million-dollar contracts that led to recklessness and drug overdoses (including Ol' Dirty Bastard's untimely death). More than simply a history of a single group, this book tells the story of a musical and cultural shift that started on the streets of Shaolin (Staten Island) and quickly spread around the world.

Biographies on such an influential outfit are surprisingly few, mostly focused on a single member of the group's story. This book weaves together interviews from all the Clan members, as well as their friends, family and collaborators to create a compelling narrative and the most three-dimensional portrait of Wu-Tang to date. It also puts The Clan within a social, cultural, and historical perspective to fully appreciate their impact and understand how they have become the cultural icons they are today. Unique in its breadth, scope, and access, From The Streets of Shaolin is a must-have for fans of WTC and music bios in general.

-

One of SLATE's "Must-Reads for Summer" (2021)

-

"Wu-Tang Clan led a revolution, and S.H. Fernando Jr. was on the front lines—at the shows, in the studio, and on set for the video shoots where these nine hip-hop warriors changed the world. With vivid reporting and sharp critical analysis, From the Streets of Shao-Lin offers a chronicle of the Wu in real time, and truly allows the reader to enter the 36 Chambers."Alan Light, former Editor-in-Chief of Vibe and Spin magazines, author of What Happened, Miss Simone?: A Biography and Let’s Go. Crazy: Prince and the Making of Purple Rain

-

“Playing chess, not checkers, author S. H. Fernando Jr. has written a blunted history of the Wu-Tang Clan that reads like a textual tapestry weaving together New York history, old school hip-hop, gritty futurism, crack corners, Five-Percent Nation knowledge, kung-fu flicks, Time Square tricks, Blaxploitation aesthetics, vintage soul, Asian philosophy, Black power, and streetwise poetics. Like the Wu crew, Fernando was driven by passion, knowledge and the desire to drop science. Master-mixing journalistic discipline and research with gonzo enthusiasm, From the Streets of Shaolin: The Wu-Tang Saga is a masterful contribution to the culture and beyond.”Michael A. Gonzales, Senior Writer, Wax Poetics

-

“S.H. Fernando Jr. is the original Wu-Tang chronicler. His early work is foundational and his latest tome delivers the titillating travels of these original men with more flavor than Flav.”Sacha Jenkins, Director, Wu-Tang Clan: Of Mics and Men

-

“To truly tell the story of a group like Wu-Tang, a writer needs to see so much more than just the music, and look deeper into the culture, sociohistorical context and sheer rawness of the streets that these young gods emerged from. It’s rare that a writer so poignantly unravels the riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma that is the Wu. S.H. Fernando Jr.’s unprecedented early access and immersion into the golden era of hip-hop lends to a deeper story of Wu-Tang’s brotherhood, visual inspirations and the gritty ecosystem that informs Wu-Tang’s come up story. From the Nation of Gods and Earths to The Zulu Nation to Raekwon’s immortal Snow Beach Polo parka, Fernando lyrically illustrates why the life and times of the Wu stands as a great American story. Beautifully nuanced and lushly written, Fernando’s telling of the Wu-Tang story shows (and proves) that it can, indeed, all be so simple.”Vikki Tobak, author and curator of Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop

-

“So much has been written about the Wu-Tang Clan, but finally we have the entire story in one place. S. H. Fernando Jr., one of the first ever journalists to cover the group, walks us through not only the backstories of the founding members, but also the specific conditions that led to Wu-Tang’s formation. Economic/racial inequality, the drug trade, the teachings of the Nation of Gods and Earths, kung fu cinema, and the early days of New York hip-hop are explained in full detail, as well as production techniques and the machinations of the music industry, with analyses of the albums (both as a group and solo projects) that took the world by storm and helped define a generation. This is an essential text for any fan of hip-hop culture or American history in general.”Ben Merlis, author of Goin’ Off: The Story of the Juice Crew & Cold Chillin’ Records

-

“An authoritative history of seminal hip-hop collective the Wu-Tang Clan…. Fernando vividly evokes the hardscrabble landscape of the group’s home turf of Staten Island, where RZA first brought them together with an ambitious vision…. The go-to source for anyone interested in one of the most significant hip-hop groups of all time.”Kirkus Reviews

-

“An undisputed labor of love, this is the account diehard fans have been waiting for.”Publishers Weekly

-

"This sweeping history of the Wu-Tang Clan, the nine-man rap crew from Staten Island whose eclectic sound transformed the genre, traces the journey of its members from their childhoods in New York City housing projects to their current role as elder statesmen of American hip-hop. If the Clan’s initial success was surprising, in an early-nineties rap scene dominated by a slick, West Coast style, its longevity has been astonishing; its various artists have produced nearly a hundred albums. Fernando dutifully narrates the group’s origin story, but his real contribution lies in a careful analysis of how its mastermind, RZA, that 'mystic, majestic magus from the slums,' created a dynasty."New Yorker

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use