Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

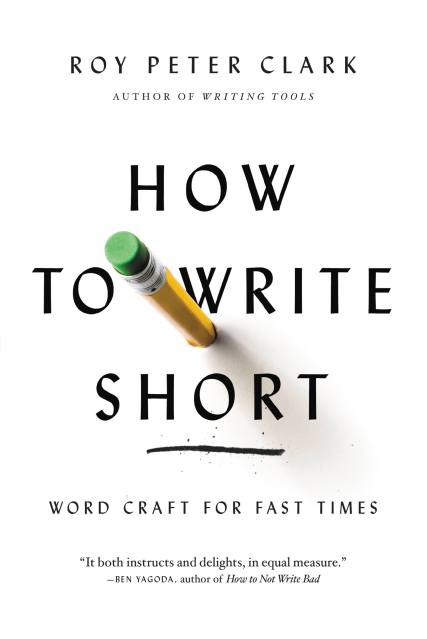

How to Write Short

Word Craft for Fast Times

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 27, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

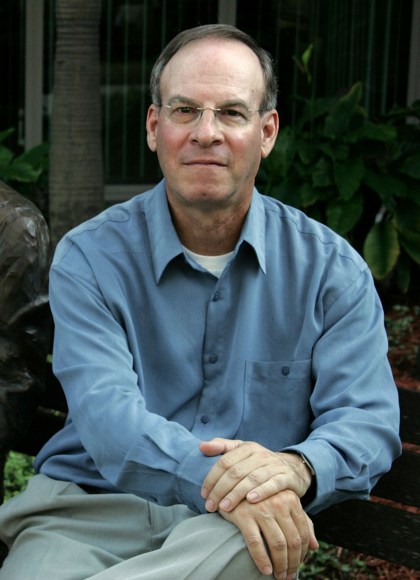

America’s most influential writing teacher offers an engaging and practical guide to effective short-form writing.

In How to Write Short, Roy Peter Clark turns his attention to the art of painting a thousand pictures with just a few words. Short forms of writing have always existed-from ship logs and telegrams to prayers and haikus. But in this ever-changing Internet age, short-form writing has become an essential skill.

Clark covers how to write effective and powerful titles, headlines, essays, sales pitches, Tweets, letters, and even self-descriptions for online dating services. With examples from the long tradition of short-form writing in Western culture, How to Write Short guides writers to crafting brilliant prose, even in 140 characters.

In How to Write Short, Roy Peter Clark turns his attention to the art of painting a thousand pictures with just a few words. Short forms of writing have always existed-from ship logs and telegrams to prayers and haikus. But in this ever-changing Internet age, short-form writing has become an essential skill.

Clark covers how to write effective and powerful titles, headlines, essays, sales pitches, Tweets, letters, and even self-descriptions for online dating services. With examples from the long tradition of short-form writing in Western culture, How to Write Short guides writers to crafting brilliant prose, even in 140 characters.

Genre:

-

"Roy Peter Clark has compressed a lifetime of learning and love of language into How to Write Short. An engaging, entertaining, indispensable guide to the art and craft of concision."

--James Geary, author of The World in a Phrase: A Brief History of the Aphorism and I Is an Other: The Secret Life of Metaphor and How It Shapes the Way We See the World -

"We're writing more than ever before, all of us, on screens big and small, and the pressure is on to make our characters count. In this book, Roy Peter Clark show us how, and more importantly, why it's worth the effort. How to Write Short is both a deeply practical guidebook and an annotated collection of concise gems from some of the world's greatest writers and journalists, not one of them longer than 300 words. Roy's message is clear: great writing is a matter of craft, not word count. How to Write Short will make you a better writer at any length."

--Robin Sloan, author of Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore

-

"How to Write Short both instructs and delights, in equal measure. On every page there is some useful advice and an amusing observation or illustration. Roy Peter Clark's many fans know that (extremely) diverse examples are one of his specialties, and this book doesn't disappoint. Open it up at random and you'll find quotes from Oscar Wilde, Steven Wright, Dorothy Parker, and Gypsy Rose Lee. And that's just one page! Read this book!"

--Ben Yagoda, author of When You Catch an Adjective, Kill It and How to Not Write Bad (forthcoming 2/2013) -

"How to Write Short comes at the perfect time and enshrines Roy Peter Clark as America's best writing coach. Who else could masterfully tease the secrets of short, powerful writing from unexpected sources -- the Bible, Shakespeare, Tom Petty, and Abe Lincoln? This book should be on every serious writer's shelf." --Ben Montgomery, staff writer, Tampa Bay Times

-

"A fun, practical guide to writing little from a guy who's written a lot. Respected journalist and writing teacher Roy Peter Clark really knows his way around a sentence. Learn from him." --Christopher Johnson, author of Microstyle: The Art of Writing Little

- On Sale

- Aug 27, 2013

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316204347

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use