Promotion

Use code BEST25 for 25% off storewide. Make sure to order by 11:59am, 12/12 for holiday delivery!

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

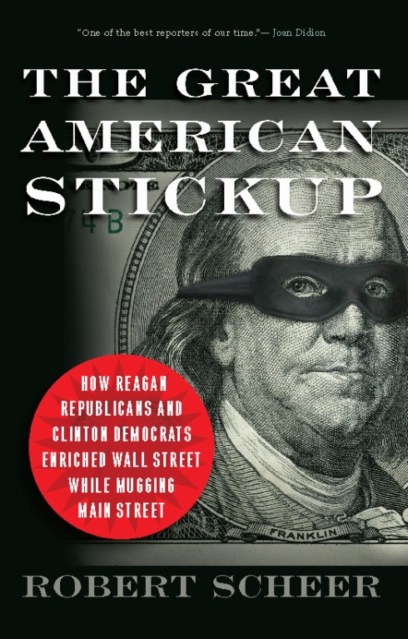

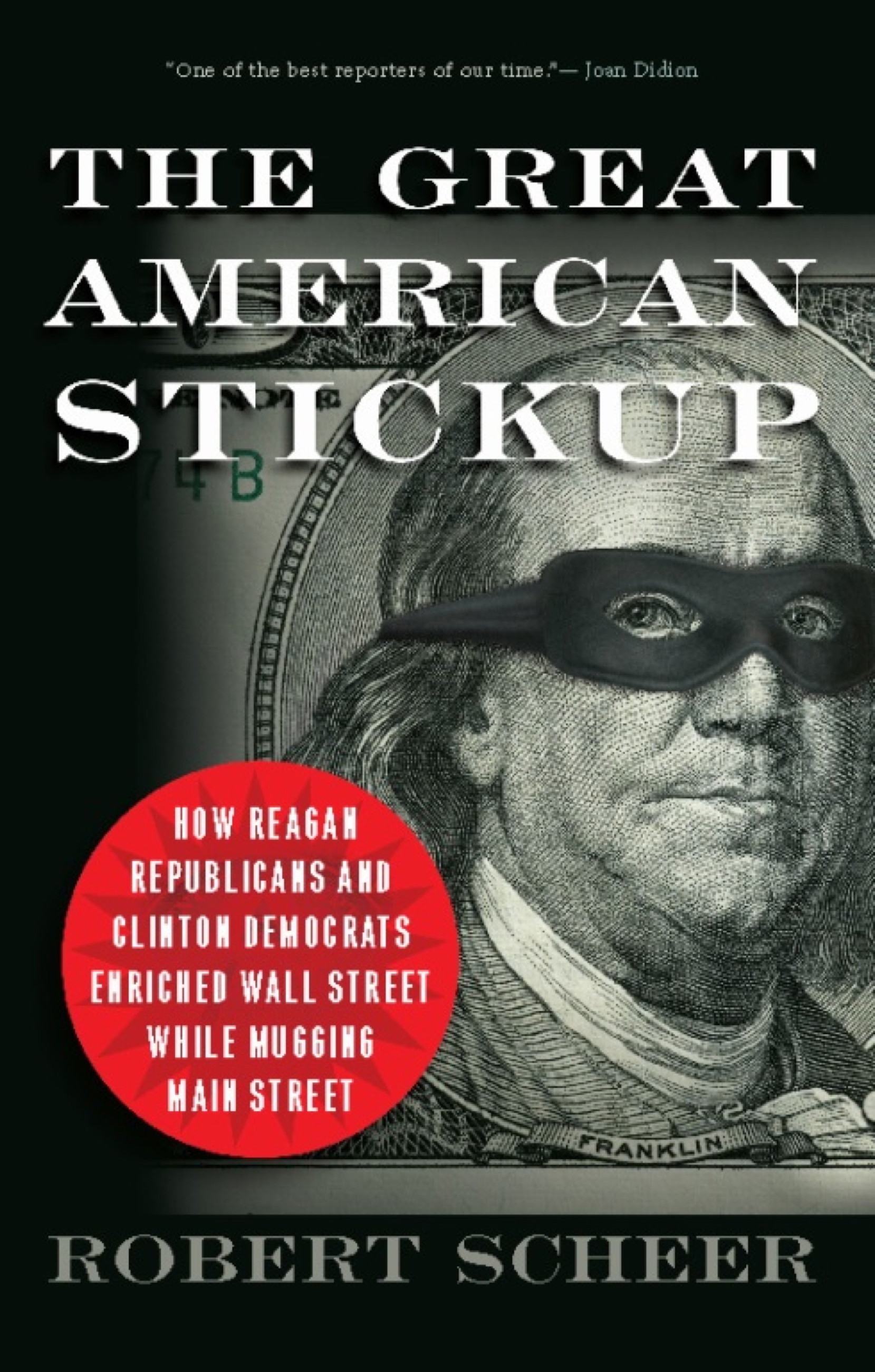

The Great American Stickup

How Reagan Republicans and Clinton Democrats Enriched Wall Street While Mugging Main Street

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 7, 2010

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568586212

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 7, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This is a story largely forgotten or overlooked by the mainstream media, who wasted more than two decades with their boosterish coverage of Wall Street. Scheer argues that the roots of the disaster go back to the free-market propaganda of the Reagan years and, most damagingly, to the bipartisan deregulation of the banking industry undertaken with the full support of “progressive” Bill Clinton.

In fact, if this debacle has a name, Scheer suggests, it is the “Clinton Bubble,” that era when the administration let its friends on Wall Street write legislation that razed decades of robust financial regulation. It was Wall Street and Democratic Party darling Robert Rubin along with his clique of economist super-friends — Alan Greenspan, Lawrence Summers, and a few others — who inflated a giant real estate bubble by purposely not regulating the derivatives market, resulting in the pain and hardship millions are experiencing now.

The Great American Stickup is both a brilliant telling of the story of the Clinton financial clique and the havoc it wrought — informed by whistleblowers such as Brooksley Born, who goes on the record for Scheer — and an unsparing anatomy of the American business and political class. It is also a cautionary tale: those who form the nucleus of the Clinton clique are now advising the Obama administration.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use