By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

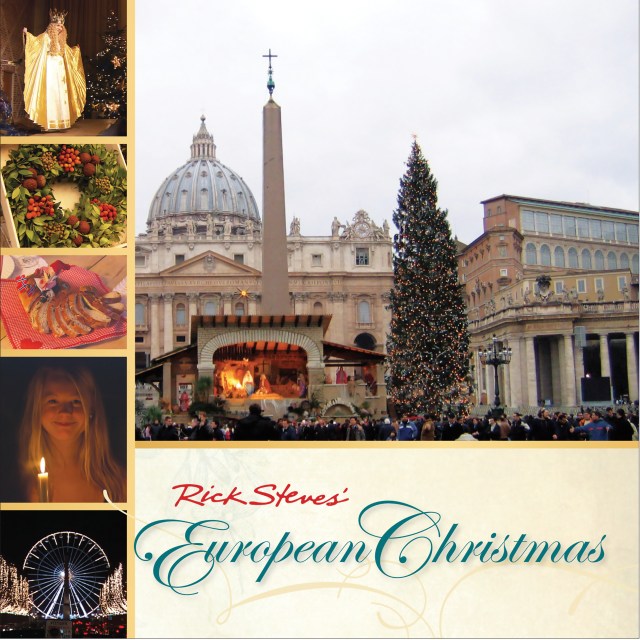

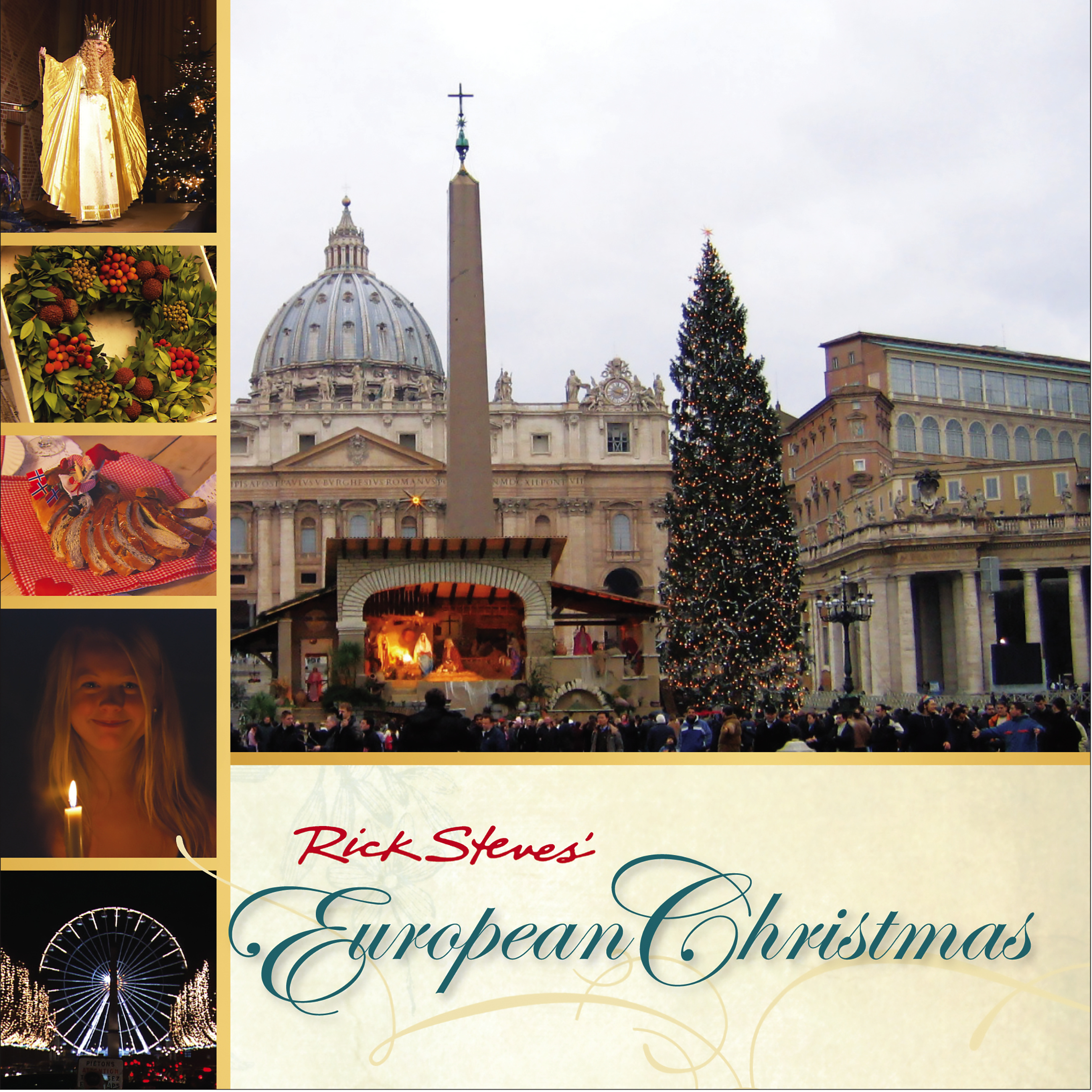

Rick Steves’ European Christmas

Contributors

By Rick Steves

By Valerie Griffith

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 27, 2013

- Page Count

- 248 pages

- Publisher

- Rick Steves

- ISBN-13

- 9781612387369

Price

$14.99Price

$19.49 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $14.99 $19.49 CAD

- ebook (Digital original) $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 27, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

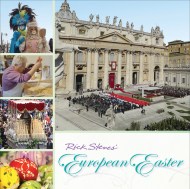

Experience the magic of Christmas in Europe with Rick Steves.

Rick Steves, America’s #1 travel authority on Europe, teams up with co-author Valerie Griffith to explore the rich and fascinating mix of traditions—Christian, pagan, musical, and edible—that led to the Christmas festivities we enjoy today.

Join Rick as he reveals an authentic, surprising portrait of holiday celebrations in England, Norway, France, Germany, Austria, Italy, and Switzerland: Romans cook up eels, Salzburgers shoot off guns, Germans buy “prune people” at markets, Norwegian kids hope to win marzipan pigs, and Parisians ice-skate on the Eiffel Tower.

With thoughtful insights, vibrant photos, and more than a dozen recipes, this great gift book captures the spirit of the season. It’s a delightful way to learn something new about Christmas.

Rick Steves, America’s #1 travel authority on Europe, teams up with co-author Valerie Griffith to explore the rich and fascinating mix of traditions—Christian, pagan, musical, and edible—that led to the Christmas festivities we enjoy today.

Join Rick as he reveals an authentic, surprising portrait of holiday celebrations in England, Norway, France, Germany, Austria, Italy, and Switzerland: Romans cook up eels, Salzburgers shoot off guns, Germans buy “prune people” at markets, Norwegian kids hope to win marzipan pigs, and Parisians ice-skate on the Eiffel Tower.

With thoughtful insights, vibrant photos, and more than a dozen recipes, this great gift book captures the spirit of the season. It’s a delightful way to learn something new about Christmas.

Series:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use