Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

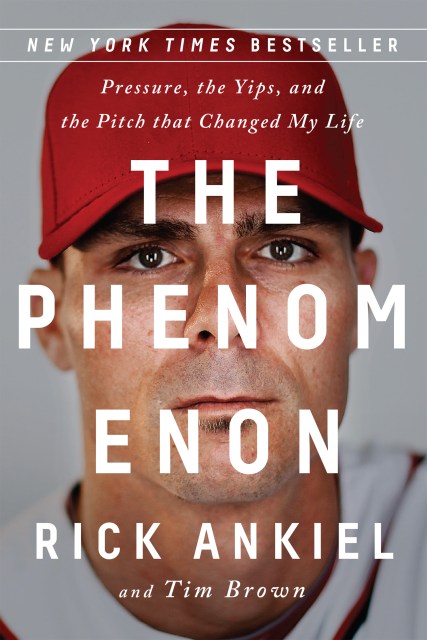

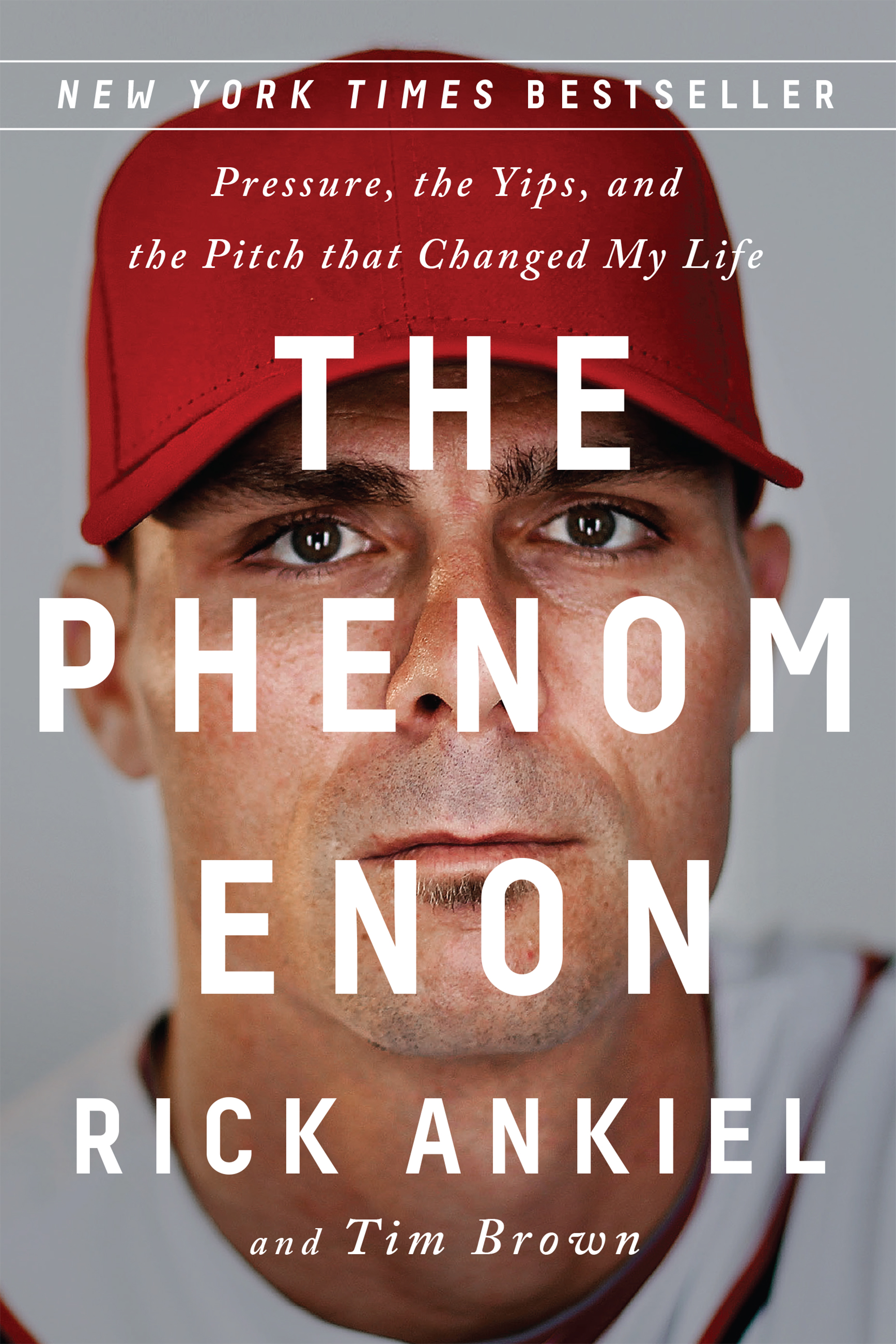

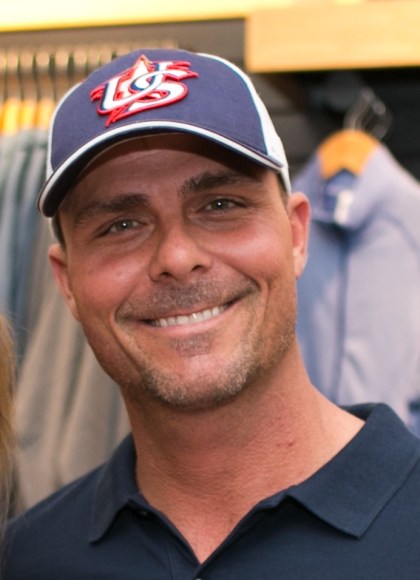

The Phenomenon

Pressure, the Yips, and the Pitch that Changed My Life

Contributors

By Rick Ankiel

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 18, 2017

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610396875

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 18, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The Phenomenon is the story of how St. Louis Cardinals prodigy Rick Ankiel lost his once-in-a-generation ability to pitch — not due to an injury or a bolt of lightning, but a mysterious anxiety condition widely known as “the Yips.” It came without warning, in the middle of a playoff game, with millions of people watching. And it has never gone away.

Yet the true test of Ankiel’s character came not on the mound, but in the long days and nights that followed as he searched for a way to get back in the game. For four and a half years, he fought the Yips with every arrow in his quiver: psychotherapy, medication, deep-breathing exercises, self-help books, and, eventually, vodka. And then, after reconsidering his whole life at the age of twenty-five, Ankiel made an amazing turnaround: returning to the Major Leagues as a hitter and playing seven successful seasons.

This book is an incredible story about a universal experience — pressure — and what happened when a person on the brink had to make a choice about who he was going to be.

-

"Revealing, vulnerable, and triumphant, Rick Ankiel and Tim Brown provide a poignant reminder in this age of statistics- and computer-driven analysis that it is real people who play the game. Real people, carrying family history, huge expectations, and lifelong dreams along for the ride. This book will change how you watch the game and those who play it." --Jim Abbott, former MLB pitcher and bestselling author of Imperfect

-

"Each year lots of baseball books roll off the presses. Some are very good, a few are extraordinary. Rick Ankiel's memoir falls into the second category. A story of rare promise and bewildering pain. The heartbreak, the humiliation and the high points - fewer than expected, but memorable still. All told with honesty, humility, empathy and an eye for telling detail. A winding and often bumpy road that ends with perhaps that best of victories - good-natured acceptance and the personal understanding and insight that goes with it."--Bob Costas

-

"In Tim Brown's expert hands, RIck Ankiel's journey is heartbreaking, unsentimental, and, in an entirely unexpected way, victorious. A superb book not just about the glory of baseball, but about how we repair ourselves."-Mark Kriegel, author of Namath, Pistol, and The Good Son

-

"Rick Ankiel has always been a true phenomenon. He had phenomenal talent, and when he faced hardship, he proved he had phenomenal character too. His book is a candid and powerful story of his pitching success, his cruel and dramatic career derailment, and his historic resurrection as a power-hitting outfielder. Your lasting impression is of Rick the winner and champion husband, father, and person, with a story that impacts us all."--Tony La Russa, Hall of Fame manager

-

"Many of us took one look at Rick Ankiel's extraordinary athletic gifts and figured that he had it made. But his great talent did not account for the inexplicable demons that he had to endure, from an abusive home to a career-altering mystery. The Phenomenon is bravely candid about his challenges in life and his journey through a game that humbles all of us."--Hall of Famer Joe Torre, four-time World Series Championship manager and MLB's chief baseball officer

-

"A great story of a young man's ability to persist in the face of complicated and difficult issues--I admire him for it and the success he eventually achieved."--Bill Parcells, Hall of Fame NFL coach

-

"The Phenomenon is a must-read for anyone who has wrestled with his own demons--which is everyone. I couldn't put this book down, maybe because I knew parts of the story, but more likely because it displays the power of the human spirit to overcome the odds."--Mike Matheny, manager of the St. Louis Cardinals

-

"Ankiel's battle with this mysterious mental block and his decision to remake his baseball career as an outfielder is tolf in The Phenomenon, an out-of-the-ordinary story of baseball courage and determination."--Christian Science Monitor

-

"A former Major League Baseball player offers an affecting account of his unique professional career and dramatic personal life. Most baseball memoirs hold little appeal for readers who are not already devoted fans. With assistance from sports journalist Brown (co-author, with Jim Abbott: Imperfect: An Improbable Life, 2012), Ankiel offers more... A solid sports memoir that explores more than just sports."--Kirkus

-

"In his surprisingly open and compelling memoir-a standout in the motley genre of athlete autobiographies-Ankiel details his many efforts to cope with the problem, from drinking to drugs to a brief retirement to deciding that he'd rather forget pitching altogether, returning as a hitter and an outfielder instead."The Atlantic

-

"This book is a moving read as Ankiel bares his soul and provides the reader with an intimate look at the psychological unraveling he experienced... To throw in a baseball cliché, Ankiel left it all on the field with this book. Don't miss it."Washington Times

-

"I strongly recommend this book. I'm a sucker for happy endings, and this isn't your classic happy ending. But Ankiel the hitter, and Ankiel in his post-career world, and Ankiel the dad breaking the chain with his own father, is one redemptive story."Peter King, Sports Illustrated

-

"For those interested in the psychology of baseball, Ankiel's book bats close to .400."St Louis Dispatch

-

"What happened to Rick Ankiel is one of the more remarkable stories in baseball history... This riveting story will make you feel Ankiel's anxiety about battling this mysterious affliction."Chicago Tribune

-

"It's a much-needed narrative in the sports memoir genre, one that tackles the topic of mental health, something only a few books before it have done"Literary Hub