Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

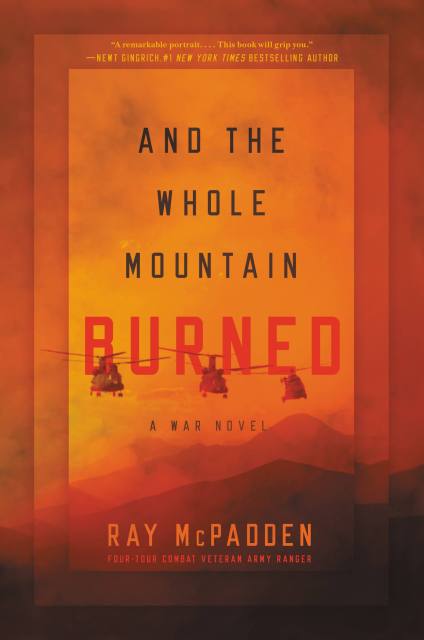

And the Whole Mountain Burned

A War Novel

Contributors

By Ray McPadden

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $26.00 $34.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Four-tour combat veteran Ray McPadden offers a vivid portrayal of American soldiers facing an unseen enemy and death in the Mountains of Afghanistan.

Sergeant Nick Burch has returned to the crags of tribal Afghanistan seeking vengeance. Burch’s platoon has one goal: to capture or kill an elusive insurgent, known as the Egyptian, a leader who is as much myth as he is man, highly revered and guarded by ferocious guerrillas. The soldiers of Burch’s platoon look to him for leadership, but as the Egyptian slips farther out of reach, so too does Burch’s battle-worn grasp on reality.

Private Danny Shane, the youngest soldier in the platoon, is learning how to survive. For Shane, hunting the Egyptian is secondary. First he must adapt to the savage conditions of the battlefield: crippling heat, ravenous sand fleas, winds thick with moondust, and a vast mountain range that holds many secrets. Shane is soon chiseled by combat, shackled by loyalty, and unflinchingly marching toward a battle from which there is no return. A new enemy has emerged, one who has studied the American soldiers and adapted to their tactics. Known as Habibullah, a teenage son of the people, he stands in brazen defiance of the Ameriki who have come to destroy what his ancestors have built. The American soldiers may be tracking the Egyptian, but Habibullah is tracking them, and he knows these lands far better than they do.

With guns on full-auto, Shane and Burch trek into the deepest solitudes of the Himalayas. Under soaring peaks, dark instinct is laid bare. To survive, Shane and Burch must defeat not just Habibullah’s militia but the beast inside themselves.

And the Whole Mountain Burned reveals, in stunning, ruthless detail, the horrors of war, the courage of soldiers, and the fact that no matter how many enemies we vanquish, there is always another just over the next ridge.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Nov 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781546081920

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use