By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

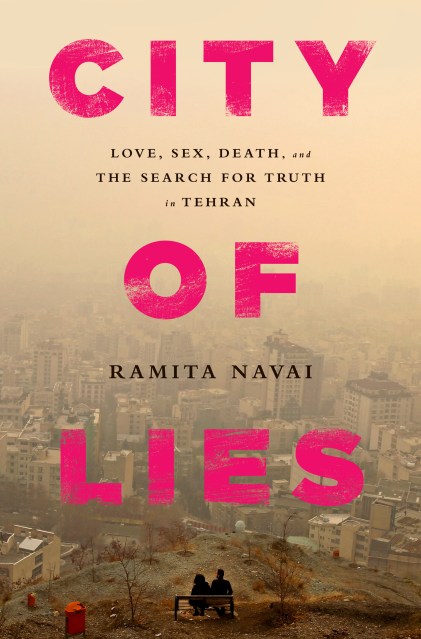

City of Lies

Love, Sex, Death, and the Search for Truth in Tehran

Contributors

By Ramita Navai

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 2, 2014

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610395205

Price

$11.99Format

Format:

- ebook $11.99

- Trade Paperback $16.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 2, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Rich and absorbing, this book travels up and down Vali Asr Street, Tehran's pulsing thoroughfare, from the lavish shopping malls of Tajrish through the smog that lingers over the alleyways and bazaars of the city's southern districts.

Ramita Navai gives voice to ordinary Iranians forced to live extraordinary lives: the porn star, the aging socialite, the assassin and enemy of the state who ends up working for the Republic, the dutiful housewife who files for divorce, and the old-time thug running a gambling den.

In today's Tehran, intrigues abound and survival depends on an intricate network of falsehoods: mullahs visit prostitutes, local mosques train barely pubescent boys in crowd control tactics, and cosmetic surgeons promise to restore girls' virginity. Navai paints an intimate portrait of those discreet recesses in a city where the difference between modesty and profanity, loyalty and betrayal, honor and disgrace is often no more than the believability of a lie.

Genre:

-

“A masterpiece of true tales turned into rich, gripping, vivid narrative… The amazing aspect of the book is that Navai manages to transform every tale into exquisitely detailed, terrible — but somehow wonderful — novellas. …There's something cinematic in Navai's style. Any one of these stories could be adapted for the big screen as a feature film…. This book is a caution, a tragedy, a seduction.”— Liz Smith, The Chicago Tribune /The Boston Herald

"This is an important book. A seamless literary tapestry that just happens to be true. Ramita Navai's collection of stories are uniquely Iranian yet they will move, chill and delight even a reader indifferent to Persia." — Sam Kiley, author of Desperate Glory and Sky News Foreign Affairs Editor

"One of the world's most exciting cities, as revealed by one of journalism's most exciting women. Navai slips effortlessly into the boots of earthy, urban writer to tour Tehran's ripped backsides in this intimate, grand guignol debut. She transports us through the Iranian capital's multiple personas with deft and knowing navigation: never short of love for even the lowliest of her fellow Tehranis. An intimate and devoted portrait, lifting a beautiful truth from a city masked in lies.” — Anthony Loyd, author of Another Bloody Love Letter and My War Gone by, I Miss it So -

“It's a well-paced, entertaining read. But its fascinating mix of characters and its refusal to be distracted by Iran's many external problems are what make City of Lies truly valuable."— The National Interest

“An intriguing collection of cameo portraits to illustrate the difficulties and challenges Tehranis face in their everyday lives… Navai provides a fascinating insight into the routine hypocrisy and dishonesty that have become the survival mechanism for millions of ordinary city-dwellers.”—Mail on Sunday (UK) -

“Taken together, the book's eight compulsively readable chapters, each focused on a different Iranian, paint a harrowing portrait of the city today… Readers are granted a panoramic view of Tehrani society: from the faux-Greek mansions that house the nouveau riche in the city's north, to a midtown bustling with students, merchants and young women with ‘enough make-up to make a drag queen recoil,' to the shacks and poverty of south Tehran.” —Wall Street Journal

"City of Lies explores the double lives led by Tehranis as they evade the watchful eye of the regime... a rich portrait of this vibrant, opaque and paranoid city... at the heart of City of Lies is some brilliant reporting. Persuading subjects to talk, even anonymously, is an achievement where betrayal is commonplace and there is always someone watching. Black humour runs through the book."— Hugh Tomlinson, The Times (UK)

"The stories are beautiful, and they're so well-detailed and nuanced." —Jon Stewart, The Daily Show

“[Navai's] beautifully written book captures the pace, pulse and passions of day-to-day existence.”— Minneapolis Star-Tribune -

“The stories are real. But they are written in a lively style that reads like a novel. Navai is impressive as a reporter, finding these characters and convincing them to share their stories. She also is an eloquent writer who uses her subjects to tell the larger tale of the degradation of the Iranian culture.”— Bookpage

“A daring exposé of what really goes on under the noses of the morality police in this God-fearing city of 12 million…. British-Iranian journalist Navai protects the real identities of her subjects, who are as engaging as characters of fiction and reveal, frankly, the charade that living under Sharia law has become since Iran's Islamic Revolution….Navai offers sharply rendered portraits.”— Kirkus

"Ramita Navai's City of Lies is gripping, a dark, delicious unveiling of the secret decadent life of Islamic Tehran, deeply researched yet as exciting as a novel" —Simon Sebag Montefiore, author of Jerusalem: The Biography, Young Stalin and One Night in Winter

“... she has broken taboos and laid bare what everyone knows but nobody mentions...She writes well and with fluency, in tight prose mercifully free of Persian hyperbole” —Antony Wynn, The Times Literary Supplement (UK) -

“[Navai's] Iranians share stories intimate and unforgettable enough to establish City of Lies as a remarkable and highly readable map of its human geography.…The stories are almost unbelievable. They reveal a Tehran so riddled with social, political, sexual and religious contradictions that it's difficult to imagine how someone could navigate the fraught maze of daily life. Navai stunned this reader with her attention to detail… Navai's prose is startling.”—Eliza Griswold, The Sunday Telegraph (UK)

"City of Lies is thoroughly researched and deeply evocative of place. Navai has a formidable talent as a storyteller. Her stories are by turns comical, intriguing and heart-wrenching. And although there's a great deal of sadness in the stories she tells, she writes with obvious love for the wondrous variety of life in Tehran."—Bijan Omrani, Geographical Magazine

"City of Lies is a fascinating account of ordinary life in a major city where religious fanaticism has been allowed to run riot. It's hard to close the book without valuing the freedom secularisation brings, and the relative absence of hypocrisy that arrives through not having to repress human nature." — Entertainment Focus -

"Welcome to life in the Islamic Republic of Iran - or, more specifically, in its teeming, ugly, catastrophically polluted capital city. Ramita Navai is an award-winning British-Iranian journalist and broadcaster who has lived in Tehran and London, and feels allegiance to both countries. It was while working as a newspaper correspondent in Tehran that she began interviewing a wide range of ordinary people about their lives, collecting stories which are (unsurprisingly) extraordinary. This gripping book is a mosaic of such glimpses into a very different world... the chapters read like utterly compelling short tales, catapulting us imaginatively into the hearts and minds of people we feel we know, even though their lives are so very 'other'... It is the author's considerable achievement to make you feel deeply moved by these lives - even as you send up a fervent prayer of gratitude that we were lucky enough to be born here."— Bel Mooney, The Daily Mail (UK)

‘Navai's Tehran teems with crystal meth pushers, gun runners, prostitutes and transexuals... what makes City of Lies engaging is that it is rooted in real-life stories... It is, in many ways, the written version of a television docudrama, with parallel stories that never intersect."— Farah Nayeri, The Independent (UK) -

*Winner of the Paddy Power Debut Political Book of the Year (UK)*

“City of Lies is an extraordinary insight into a country barely known—and often feared—by the West.” —Vogue

“A great read. She takes readers to corners of Iranian society that are very difficult to penetrate. And she does that with great personal risk.” —PRI's The World, favorite books of 2014

"Telling the story of Tehran through a cast of characters...Navai illustrates how Iranians are far more bound by what they have in common: a strong awareness of class, an irrepressible drive for upward mobility, daily clashes with the forces of modernity and tradition, and a profound disillusionment with the opportunities society has on offer. Fast-paced and saturated with detail each chapter describes a Tehrani whose life the treacherous, glittering city has disfigured in some way... what [Navai] has done is extraordinary. Despite the bleakness of life in their "city of lies", her Iranians continue to soldier on, hoping the future holds something better.”—Azadeh Moaveni, Financial Times (UK)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use