By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

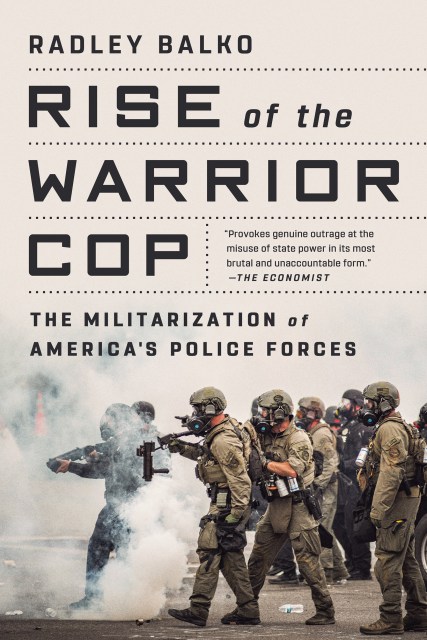

Rise of the Warrior Cop

The Militarization of America's Police Forces

Contributors

By Radley Balko

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 1, 2021

- Page Count

- 528 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541774537

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 1, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The last days of colonialism taught America’s revolutionaries that soldiers in the streets bring conflict and tyranny. As a result, our country has generally worked to keep the military out of law enforcement. But over the last two centuries, America’s cops have increasingly come to resemble ground troops. The consequences have been dire: the home is no longer a place of sanctuary, the Fourth Amendment has been gutted, and police today have been conditioned to see the citizens they serve as enemies.

In Rise of the Warrior Cop, Balko shows how politicians’ ill-considered policies and relentless declarations of war against vague enemies like crime, drugs, and terror have blurred the distinction between cop and soldier. His fascinating, frightening narrative that spans from America’s earliest days through today shows how a creeping battlefield mentality has isolated and alienated American police officers and put them on a collision course with the values of a free society.

In Rise of the Warrior Cop, Balko shows how politicians’ ill-considered policies and relentless declarations of war against vague enemies like crime, drugs, and terror have blurred the distinction between cop and soldier. His fascinating, frightening narrative that spans from America’s earliest days through today shows how a creeping battlefield mentality has isolated and alienated American police officers and put them on a collision course with the values of a free society.

Genre:

-

“Rise of the Warrior Cop asks many questions about the proper role of law enforcement and the effect of the drug war, America’s longest war, on our communities... Balko interweaves history, the Constitution, and case law to create an account of how the massive expansion of SWAT teams occurred as the perfect storm of politics, ideology and federal fiscal coercion.”Diane Goldstein, Huffington Post

-

“A fascinating and at times wrenching new book.”Sarah Stillman, New Yorker

-

“The best and most comprehensive account of the dangers of police militarization.”Glenn Greenwald, Intercept

-

“Mr. Balko manages to avoid the clichés of both right and left, and provokes genuine outrage at the misuse of state power in its most brutal and unaccountable form: heavily armed police raiding the homes of unarmed, non‑violent suspects on the flimsiest of pretexts, and behaving more like an occupying army in hostile territory than guardians of public safety. Rise of the Warrior Cop, Mr. Balko’s interesting first book, explains what policies led to the militarization of America’s police. To his credit, he focuses his outrage not on the police themselves, but on politicians and the phony, wasteful drug war they created.”Economist

-

“A well‑researched book that piques the reader’s intellect as much as it does his or her emotions.”Salt Lake Tribune

-

“This historic review of America’s police and police tactics is clear and direct in its nondismissal narrative. This is not an anti‑police book, but a serious look at the growth and use of SWAT and military style tactics, at America’s war on drugs, and the financial incentives that created the new ‘community police force’... This book is highly recommended for the historic value of the information; it is clear, concise, and well argued. Whether you are a lifetime, card carrying member of the ACLU or the newest law and order politician Rise of the Warrior Cop provides a clear timeline and important information making it a must read.”New York Journal of Books

-

“Virtually peerless as a writer on the issue.”Daily Beast

-

“Fascinating and sometimes terrifying.”Pacific Standard

-

“The best new book on a law‑related topic I have read so far this year.”Ilya Somin, Volokh Conspiracy

-

“For Americans who care about their core political liberties, Balko’s book is a must‑read.”Charleston (WV) Gazette

-

“In Balko’s hands, an entertaining and illuminating story ‑ as well as depressing and frightening ‑ told with verve and gusto, meticulously researched, and filled with telling historical detail... Rise of the Warrior Cop is an important book and deserves to be read by small government conservatives, civil libertarian liberals, police commanders, and politicians alike.”StoptheDrugWar.org

-

“It’s critical to appreciate the history of policing, to understand that what we now see as normal and inescapable wasn’t always the case. For most of our history, this country did not have a group of people with shields and guns who wandered the streets ordering people about... If there is any hope of changing the course of the militarization of law enforcement, it will come from a greater understanding of why this was never meant to be the internal norm of this country, and that it doesn’t have to be. Radley Balko has done an exceptional job of making the case. Every person who hopes to preserve the integrity of his Castle from dynamic entry needs to read Rise of Warrior Cop.”Simple Justice

-

“‘Are cops constitutional?’ It’s a bold and provocative question, and the more Balko delves into the history of law enforcement, the more that question seems worth considering. ... After reading Balko, you’ll be aware, alright‑and scared.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Excessively militarized policing is easy to ignore when a SWAT team is ramming down someone else’s door or tear‑gassing someone else’s protest. What makes Rise of the Warrior Cop so important is that Mr. Balko makes police militarization real for all of us. This is a meticulously researched history book that casts needed light on a central civil liberties issue. Police militarization is something we should all care about, and Rise of the Warrior Cop will show you why.”Anthony D. Romero, Executive Director, American Civil Liberties Union

-

“With his thorough reporting and compelling storytelling gifts, Radley Balko builds a powerful narrative of the militarization of our police forces, which both liberals and conservatives have allowed to flourish. And he shows the chilling results of both parties’ unwillingness to stand up to increasingly aggressive police tactics that often pit cops against those they are sworn to protect.”Arianna Huffington, president and editor in chief, Huffington Post

-

“Rise of the Warrior Cop is a comprehensive look at the reasons for, and the results of, the increasing militarization of law enforcement. Civil libertarians on the left and limited government conservatives on the right should pay especially close attention to Radley Balko’s examination of the link between the ‘the war on drugs’ and law enforcement’s increased use of police state tactics.”Ron Paul, former Texas congressman

-

“A rich, pertinent history, with unexpected but critically important observations of the increased militarization of American policing. And so well presented: clear, lucid, elegantly crafted. Rise of the Warrior Cop should be on the shelves of every police chief, sheriff, and SWAT commander in the country. A huge contribution.”Norm Stamper, thirty four year police veteran and police chief of Seattle, Washington, 1994 2000

-

“Vibrant and compelling. There is no vital trend in American society more overlooked than the militarization of our domestic police forces, and there is no journalist in America who is more knowledgeable and passionate about this topic than Radley Balko. If you care about the core political liberties of Americans, this is a must‑read.”Glenn Greenwald, New York Times bestselling author of How Would a Patriot Act?

-

“For all my cop’s quibbles with Rise of the Warrior Cop, I was struck by how much I found to agree with in the book. Balko makes a compelling case that in America today there are too many SWAT teams operating with too little accountability, further exposing the country to the dangers this magazine identified in 1996. ‘No, America today isn’t a police state,’ he writes in the concluding chapter. ‘Far from it. But it would be foolish to wait until it becomes one to get concerned.’ One need not be a libertarian to appreciate the warning.”“Jack Dunphy” (nom de plume of a police officer with the Los Angeles Police Department), National Review Online

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use