By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

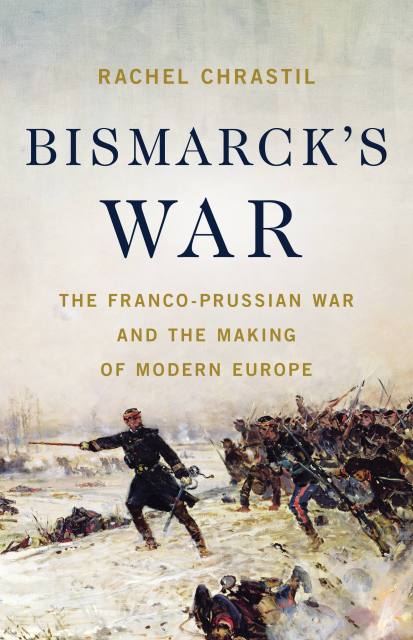

Bismarck’s War

The Franco-Prussian War and the Making of Modern Europe

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 5, 2023

- Page Count

- 512 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541604094

Price

$35.00Price

$44.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $44.00 CAD

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 5, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Among the conflicts that convulsed Europe during the nineteenth century, none was more startling and consequential than the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. Deliberately engineered by Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck, the war succeeded in shattering French supremacy, deposing Napoleon III, and uniting a new German Empire. But it also produced brutal military innovations and a precarious new imbalance of power that together set the stage for the devastating world wars of the next century.

In Bismarck’s War, historian Rachel Chrastil chronicles events on the battlefield in full, while also showing in intimate detail how the war reshaped and blurred the boundaries between civilian and soldier as the fighting swept across France. The result is the definitive history of a transformative conflict that changed Europe, and the history of warfare, forever.

Genre:

-

“A most engaging book, distinguished by sharp insight, powerful characterization and a strong narrative flow. It is the best modern account of the war.”Wall Street Journal

-

“A vivid and informative story of these events and their consequences…Chrastil’s compassionate and thought-provoking history does justice to both sides of this legacy.”Daily Telegraph

-

“This is an impressive work, fluent, wide-ranging, vivid in its use of sources, and central to an understanding of Europe’s subsequent history.”Spectator

-

“Chrastil has clearly not written one of those increasingly common recent histories of war that seem to have no battles in them. She presents a skillful account of military mechanics. Still, where Chrastil shines is in providing a broader societal portrait of the conflict, particularly in France.”Washington Examiner

-

“A welcome new addition to the literature…[Chrastil’s] book is likely to become the standard account of the war in English.”Literary Review

-

“A brisk, invigoratingly intelligent read, full of the colorful personalities that governed the war but also full of the million anonymous civilian sufferers on French soil…Bismarck's War tells this grim story with superb narrative energy.”Open Letters Review

-

“Chrastil tells the story of the war very well, skillfully weaving together its military, political, and social aspects. Her descriptions of key battles are admirably clear and accessible.”American Historical Review

-

“Engrossing narrative history that offers a great overview of the Franco-Prussian War and includes many well-selected and surprising details that have the potential to diversify and change perceptions of this important conflict even in readers who know the era well.”Engelsberg Ideas

-

“One of those rare history books that truly delivers on this kind of ambitious promise.”Quillette

-

“Marshaling a tremendous amount of information, Chrastil clearly demonstrates how this conflict set the stage for the world-shattering violence of the 20th century. It’s an outstanding synthesis of a complex and vicious war.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Rachel Chrastil colorfully describes how the Franco-Prussian War destroyed the long European peace established after Napoleon's defeat in 1815. Beginning as a midsummer cabinet war between monarchs, one of them Napoleon's nephew, Bismarck's invasion of France bogged down in winter rain and snow, and became a rancorous war of peoples that kindled the inferno of World War I.”Geoffrey Wawro, author of The Franco-Prussian War and A Mad Catastrophe

-

“Rachel Chrastil has written a fresh and compelling history of the most important European war between Waterloo and World War I. In rich and engaging detail, she shows how it laid much of the foundation for the wars of the twentieth century, even as it was seen at the time, and subsequently remembered, as a relatively conventional conflict. A tour-de-force.”David A. Bell, Princeton University

-

“Bismarck’s War brings the Franco-Prussian War to life through the words and deeds of participants both on and off the battlefield. Rachel Chrastil’s fascinating examination of the conflict compellingly narrates its military and political dimensions, and it puts the war in a global context, emphasizing its human cost and the international response to the humanitarian crisis it created. An engrossing, compassionate, and critical interrogation of a decisive historical event.”Carolyn J. Eichner, author of The Paris Commune