By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

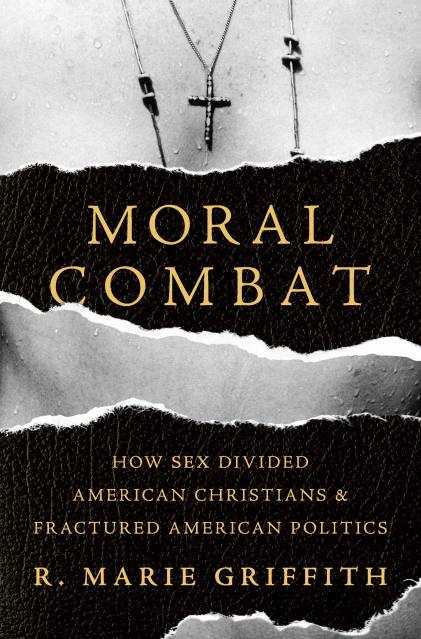

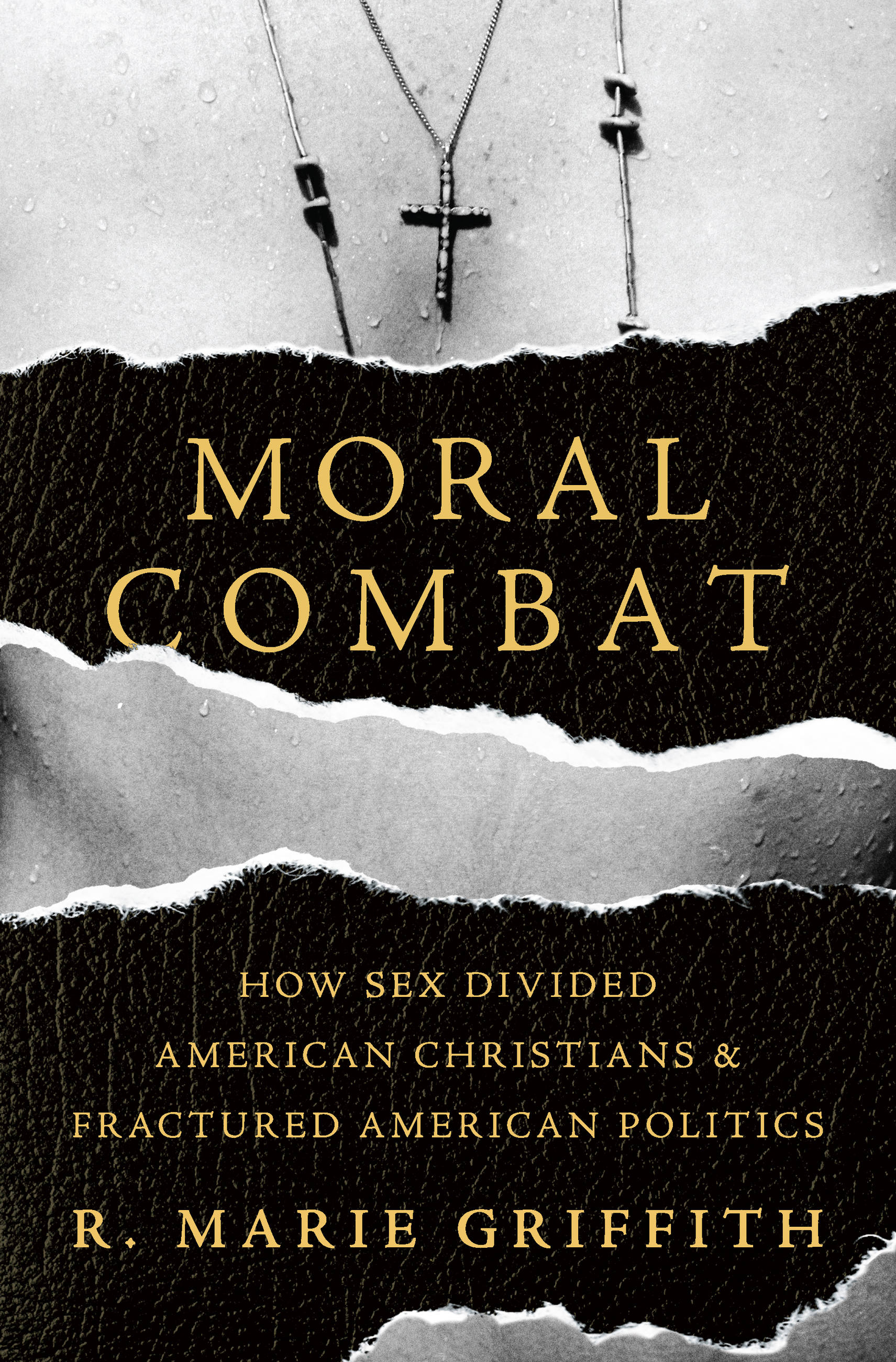

Moral Combat

How Sex Divided American Christians and Fractured American Politics

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 12, 2017

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465094769

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $51.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 12, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Gay marriage, transgender rights, birth control — sex is at the heart of many of the most divisive political issues of our age. The origins of these conflicts, historian R. Marie Griffith argues, lie in sharp disagreements that emerged among American Christians a century ago. From the 1920s onward, a once-solid Christian consensus regarding gender roles and sexual morality began to crumble, as liberal Protestants sparred with fundamentalists and Catholics over questions of obscenity, sex education, and abortion. Both those who advocated for greater openness in sexual matters and those who resisted new sexual norms turned to politics to pursue their moral visions for the nation. Moral Combat is a history of how the Christian consensus on sex unraveled, and how this unraveling has made our political battles over sex so ferocious and so intractable.