Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

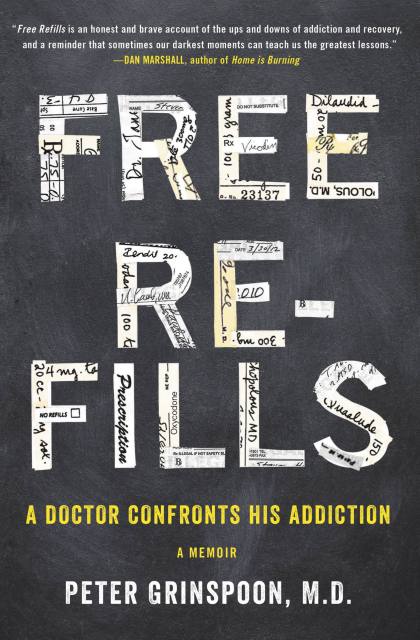

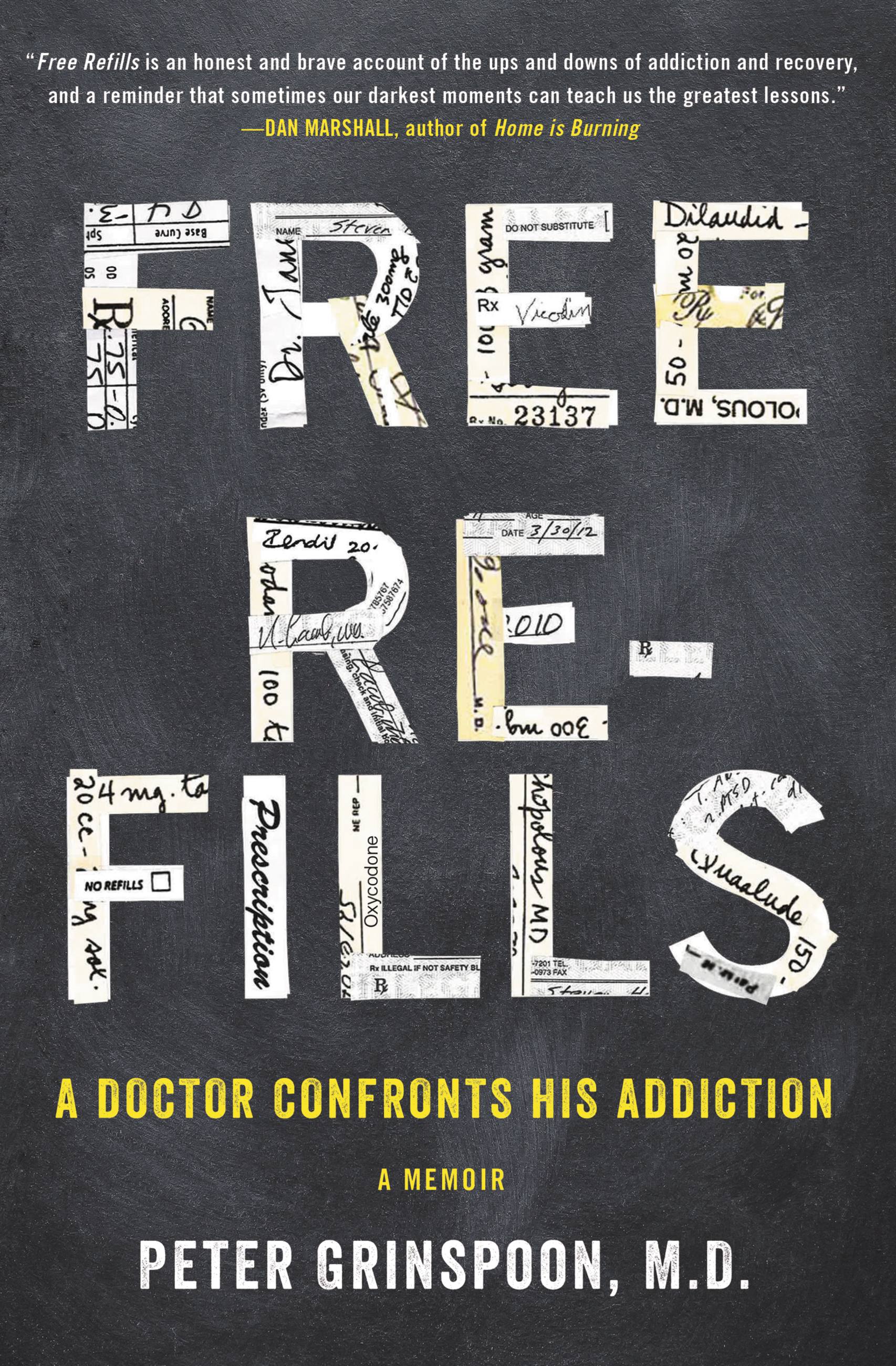

Free Refills

A Doctor Confronts His Addiction

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 16, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Dr. Peter Grinspoon seemed to be a total success: a Harvard-educated M.D. with a thriving practice; married with two great kids and a gorgeous wife; a pillar of his community. But lurking beneath the thin veneer of having it all was an addict fueled on a daily boatload of prescription meds. When the police finally came calling–after a tip from a sharp-eyed pharmacist–Grinspoon’s house of cards came tumbling down fast. His professional ego turned out to be an impediment to getting clean as he cycled through recovery to relapse, his reputation, family life, and lifestyle in ruins. What finally moves him to recover and reclaim life–including working with other physicians who themselves are addicts–makes for inspiring reading.

-

"[A] very honest story of dependence and redemption."New York Post

-

"When two detectives showed up at Peter Grinspoon's medical practice informing him he was being charged with fraudulently obtaining controlled substances, he knew he was screwed. Not because he was being falsely accused, but because it was true. In Free Refills, Grinspoon takes us down into the special hell that is addiction-in his case it was a raging addiction to opiates that, conveniently, he could write his own prescriptions for. With sharp, dark wit, Grinspoon maintains his sense of humor in the face of near defeat, as he struggles to get (and stay) clean while his life comes apart at the seams. Free Refills is a self-deprecating, brutally honest, and surprisingly hilarious read. You can't help but root for the good doctor."Dan Lyons, author of Disrupted and co-writer/producer of HBO's Silicon Valley

-

"Dr. Grinspoon bravely lays his complex soul bare as he tumbles from Harvard star doctor to addicted criminal. In this deeply affecting ride through the contradictions of addiction, we cringe at his arrogance, resentment, and self-justification while loving his compassion, commitment, and gratitude. We laugh at his cynical disdain for the simplistic platitudes and punitive inanity of the recovery world, but feel his pain as he learns humility and permits his best self to emerge. It's a process of discovery I hope to encourage in my patients, and provides hope without sugar-coating. This is an important book for doctors and patients that blurs the boundaries because it is so fundamentally human."Dr. Mark Green, addictions specialist at Psych Garden

-

"Free Refills is an honest and brave account of the ups and downs of addiction and recovery, and a reminder that sometimes our darkest moments can teach us the greatest lessons."Dan Marshall, author of Home is Burning

-

"Enlightening and intimate, this book will hold the attention of medical professionals, addiction counselors, and those affected by substance abuse."Library Journal

-

"[A] candid and darkly witty memoir that not only tells his story but shines a light on the growing problem of substance use disorders in the medical profession."Elementsbehavioralhealth.com

- On Sale

- Feb 16, 2016

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316382687

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use