By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

Hitler’s First Hundred Days

When Germans Embraced the Third Reich

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 17, 2020

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541697447

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $29.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 17, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

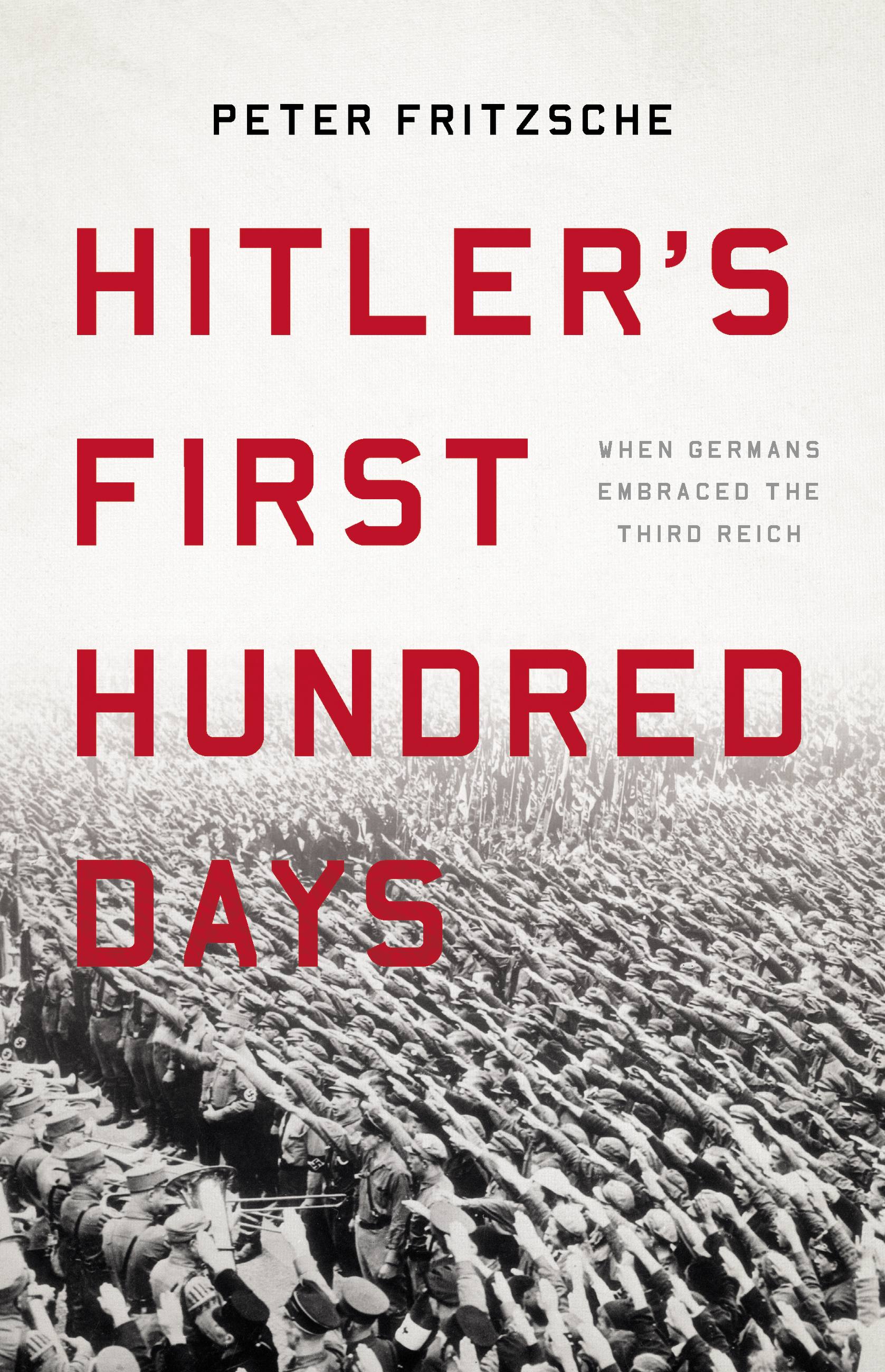

Amid the ravages of economic depression, Germans in the early 1930s were pulled to political extremes both left and right. Then, in the spring of 1933, Germany turned itself inside out, from a deeply divided republic into a one-party dictatorship. In Hitler's First Hundred Days, award-winning historian Peter Fritzsche offers a probing account of the pivotal moments when the majority of Germans seemed, all at once, to join the Nazis to construct the Third Reich. Fritzsche examines the events of the period—the elections and mass arrests, the bonfires and gunfire, the patriotic rallies and anti-Jewish boycotts—to understand both the terrifying power the National Socialists exerted over ordinary Germans and the powerful appeal of the new era they promised.

Hitler's First Hundred Days is the chilling story of the beginning of the end, when one hundred days inaugurated a new thousand-year Reich.

Genre:

-

"Elegant and sobering"New York Times

-

"Perceptive."Wall Street Journal

-

“A dramatic retelling….It is [Fritzche’s] capacity for turning the lens back onto the viewer that makes his work so profound and so convincing.”New York Times Book Review

-

“Fritzsche makes the telling argument that violence not only silenced Nazi opponents but was also essential to building support.”New York Review of Books

-

"A brilliant, quietly horrifying new anatomy of precisely how Germany went from a traumatized and fragmented republic to a Nazi dictatorship."Christian Science Monitor

-

"Masterly...While Hitler's First Hundred Days is laden with lessons for contemporary political observers (let alone students of any era of modern political history), Fritzsche is not a prisoner of the moment. He has instead made a substantial contribution to the historical scholarship on Nazi Germany."New Criterion

-

"Extensive primary sources, including novels, films, journalism, and diplomatic memos...animate the means through which Hitler's system fused party with nation and forged ordinary Germans into Nazis."Airmail

-

"In the first 100 days of Adolf Hitler's appointment as chancellor in 1933, Germany transformed from a troubled democracy to a country that put into practice extreme repression and limitations on personal freedom...Everyone concerned about the rise of nationalism, the impact of extreme partisanship, and preserving democracy should read this insightful book."Library Journal, starred review

-

"Hitler had little trouble destroying German democracy, and this fine history describes how he did it....A painful but expert historical account."Kirkus

-

"Skillfully interweaving anecdotal accounts with big-picture analysis, Fritzsche deepens readers' understanding of how Hitler consolidated power. This is a worthy look at a moment too often hurried through in histories of the period."Publishers Weekly

-

"Not all 100 days are the same. This riveting and troubling portrait of political and social depredation by a master historian of the Third Reich underscores liberal democratic frailty in the face of fierce determined attack. As such, it implicitly offers readers a clarion call to take incipient and assertive authoritarianism seriously lest they create an ugly new normal."Ira Katznelson, author of Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time

-

"Hitler's First Hundred Days is gripping from the first lines. With elegance and deep knowledge, Peter Fritzsche tells the story of how Hitler and the Nazis consolidated their hold on power in the spring of 1933. Fritzsche knows this ground like few others, and his eye for the telling detail makes this book surprising at every turn, even as he shows how the story is chillingly relevant to our times."Benjamin Hett, author of The Death of Democracy: Hitler's Rise to Power and the Downfall of the Weimar Republic

-

"If you have ever wanted to gain a better understanding of when, how, and why a critical mass of Germans turned themselves over to a pathological populist ideologue like Adolf Hitler, enthusiastically embracing his brand of exclusionary tribalism against a backdrop of economic dislocation, societal polarization, and state-sponsored terror, this is the book for you. Solidly researched and gracefully written, acclaimed historian Peter Fritzsche's Hitler's First Hundred Days is also timely, very timely indeed."David Clay Large, author of Berlin and Where Ghosts Walked: Munich's Road to the Third Reich

-

"Hitler's First Hundred Days, a thoroughly researched and elegantly written book, is a must for understanding how a majority of Germans adapted to the new regime, even cheered it, merely a few months after Hitler's accession to the chancellorship. A stark reminder of the blandishments of power."Saul Friedlander, Professor Emeritus of History at UCLA and author of Nazi Germany and the Jews