Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

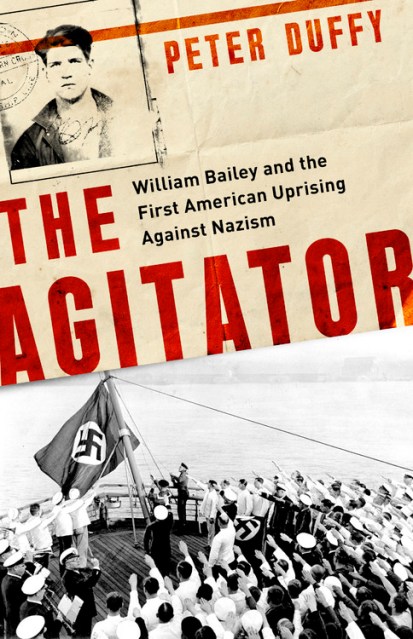

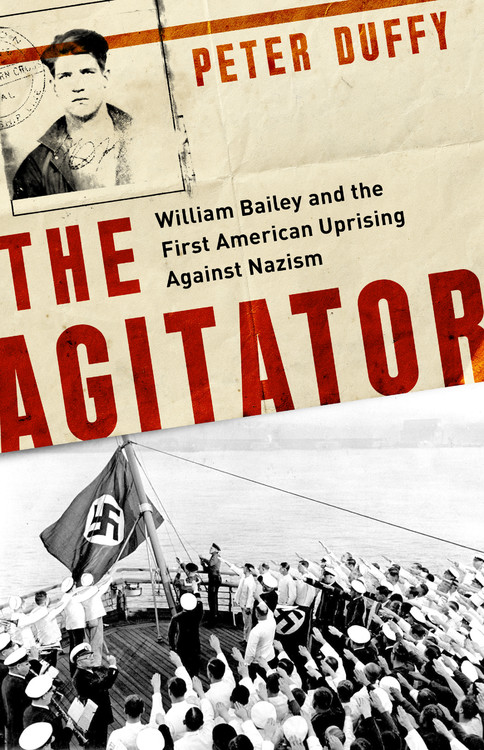

The Agitator

William Bailey and the First American Uprising against Nazism

Contributors

By Peter Duffy

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 19, 2019

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541762312

Price

$36.00Price

$46.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 19, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

By 1935, Hitler had suppressed all internal opposition and established himself as Germany’s unchallenged dictator. Yet many Americans remained largely indifferent as he turned his dangerous ambitions abroad. Not William Bailey.

Just days after violent anti-Semitic riots had broken out in Berlin, the SS Bremen, the flagship of Hitler’s commercial armada, was welcomed into New York Harbor. Bailey led a small group that slipped past security and cut down the Nazi flag from the boat in the middle of a lavish party. A brawl ensued, followed by a media circus and a trial, in which Bailey and his team were stunningly acquitted. The political victory ultimately exposed Hitler’s narcissism and violent aggression for all of America to see.

The Agitator is the captivating story of Bailey’s courage and vision in the Bremen incident, the pinnacle of a life spent battling against fascism. Bailey’s story is full of drama and heart–and it’s an inspiration to anyone who seeks to resist tyranny.