Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

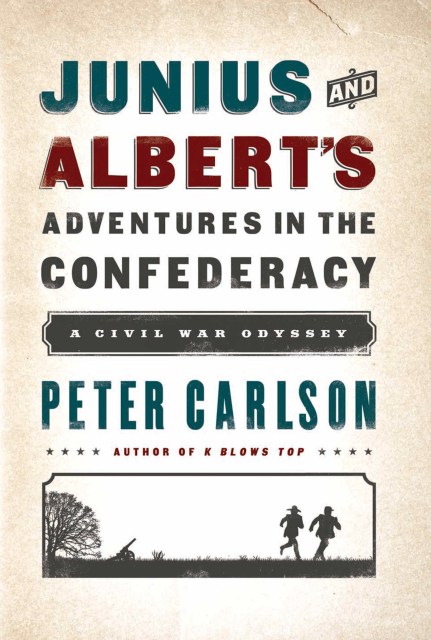

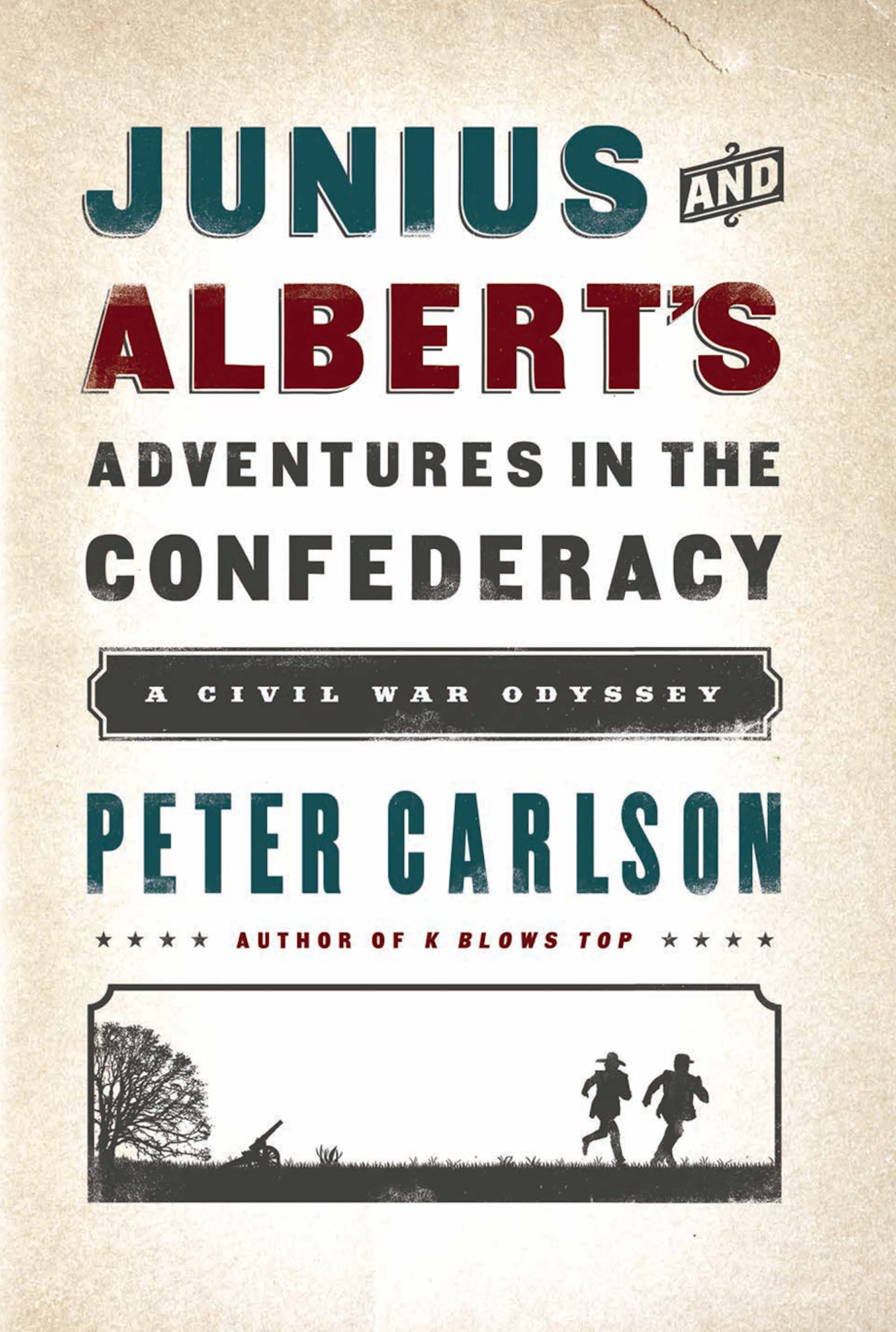

Junius and Albert's Adventures in the Confederacy

A Civil War Odyssey

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 28, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

On their long, strange adventure, Junius and Albert encountered an astonishing variety of American characters — Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant, Rebel con men and Union spies, a Confederate pirate-turned-playwright, a sadistic hangman nicknamed “the Anti-Christ,” a secret society called the Heroes of America, a Union guerrilla convinced that God protected him from Confederate bullets, and a mysterious teenage girl who rode to their rescue at just the right moment.

Peter Carlson, author of the critically acclaimed K Blows Top, has, in Junius and Albert’s Adventures in the Confederacy, written a gripping story about the lifesaving power of friendship and a surreal voyage through the bloody battlefields, dark prisons, and cold mountains of the Civil War.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 28, 2013

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610391559

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use