Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

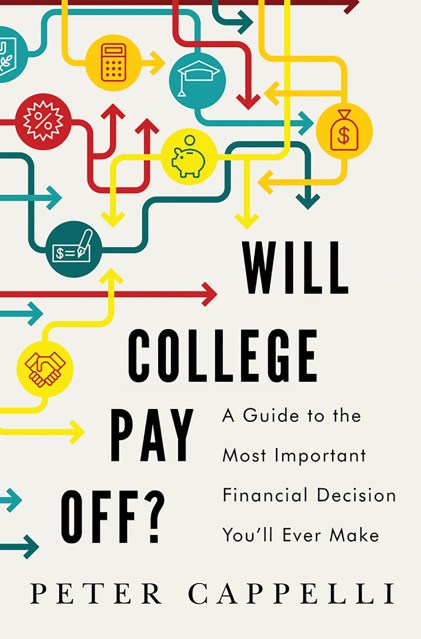

Will College Pay Off?

A Guide to the Most Important Financial Decision You'll Ever Make

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 9, 2015

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610395274

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $25.99 $32.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 9, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Adding to the confusion, the same degree can cost dramatically different amounts for different people. A barrage of advertising offers new degrees designed to lead to specific jobs, but we see no information on whether graduates ever get those jobs. Mix in a frenzied applications process, and pressure from politicians for “relevant” programs, and there is an urgent need to separate myth from reality.

Peter Cappelli, an acclaimed expert in employment trends, the workforce, and education, provides hard evidence that counters conventional wisdom and helps us make cost-effective choices. Among the issues Cappelli analyzes are:

What is the real link between a college degree and a job that enables you to pay off the cost of college, especially in a market that is in constant change?

Why it may be a mistake to pursue degrees that will land you the hottest jobs because what is hot today is unlikely to be so by the time you graduate.

Why the most expensive colleges may actually be the cheapest because of their ability to graduate students on time.

How parents and students can find out what different colleges actually deliver to students and whether it is something that employers really want.

College is the biggest expense for many families, larger even than the cost of the family home, and one that can bankrupt students and their parents if it works out poorly. Peter Cappelli offers vital insight for parents and students to make decisions that both make sense financially and provide the foundation that will help students make their way in the world.

-

“It's precisely the right moment for a book to help 18-year-olds and their parents make this important educational and financial decision... Cappelli offers some good tips: Student loans are stickier than a mortgage: You can't escape them with bankruptcy, and you may find your wages garnished if you try to walk away from them, never mind your bad credit rating. Don't rely on data released by colleges, particularly employment rates, which are often calculated based on dubious self-reporting surveys. When you visit a school, check out the tutoring center and see if anyone is around to help; it's a good proxy for the campus support system. Most important, finish on time. A surefire way to erode your return on college is to graduate late or not at all.” —Wall Street Journal

“[A]stutely examines the enduring relevance of a college degree... [I]lluminating statistical and survey data… Cappelli's eye-opening report card on the current state of American education gives mounting tuitions a failing grade... Salient reading for students, parents, and educators on navigating toward a coveted college degree.”—Kirkus Reviews

“A valuable, commonsensical analysis of an ever-more-important subject.”—Booklist